By Joseph Mathieu

Photos by Chris Roussakis

The organizers of Cinquecento had a vision: a year of events with international scholars and performers in celebration of Leonardo da Vinci, 500 years after his death, that would illuminate some of the lesser-known aspects of his life.

They took a page from da Vinci’s book, said Angelo Mingarelli, chair of Carleton University’s Leonardo 2019 committee. They just went for it.

“It’s been an incredible year,” he said. “We now have more people interested in Leonardo, the community responded and Carleton did way more than I expected.”

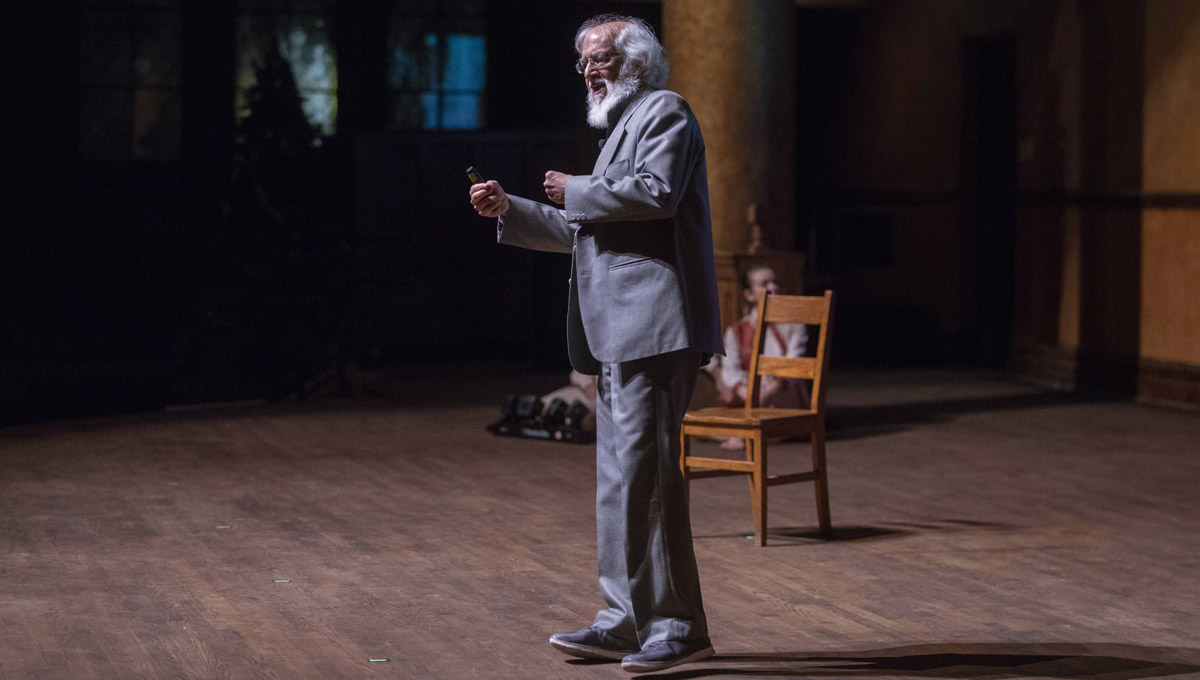

Prof. Angelo Mingarelli

The Cinquecento finale took place on Dec. 12, 2019 at the Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre, with a video highlighting events on campus and across Ottawa that involved 16 speakers and the Gruppo Jobel cultural performance organization.

With a mission to raise awareness and engagement about social and environmental issues, Gruppo Jobel created a new style of theatre in 2018 called SmarTalk blending performance art and education. Four performers alternately took on the roles of Leonardo, his inventions, and various animals and elements of nature key to his life’s work. There were also lectures from Mingarelli, a mathematics professor, and Azrieli School of Architecture Prof. H. Masud Taj.

Illuminating Leonardo’s Hopeful Messages to Future Generations

In between interpretive dance and Italian-English performances, Taj explored various facets of Leonardo’s notes. He focused on Leonardo’s mirror writing (right to left) and the imagery of the divine intersecting with that of everyday life in his famous sketch The Vitruvian Man.

The finale’s performance hinged on the idea that Leonardo’s keen observations of the natural, mechanical and human worlds were multi-faceted gifts. His enduring notebooks and his unending curiousity were hopeful messages to future generations.

“Leonardo believed that sight was mankind’s most important sense,” said a performer. “Knowing how to see was crucial to living all aspects of life fully. To develop a complete mind, Leonardo believed that you must study the science of art and also the art of science.”

Mingarelli pointed out how Leonardo’s studies of human anatomy were incorporated into his lifelike portraits. He took meticulous sketches of a corpse’s muscle and sinew in his notebooks (now called the Codex Leicester) and these exact details of neck muscles and hands are visible in his depictions of Saint Jerome and the Virgin Mary.

His realistic representations of nature — such as the caves of The Virgin of the Rocks — are also consistent throughout his works.

“Observe how these plants are not only decorative, they’re also botanically accurate,” said Taj, indicating the flowery lawn of Annunciation. “That’s so Leonardo.”

“He was perhaps one of the great mentors of my life,” said Mingarelli. “So much so that nowadays I find myself approaching nature, life, mathematics and sciences the same way he did: wanting to know everything.”

Cinquecento: A Seed Grows to Fruition

The seed was planted in 2016, when Mingarelli discussed the idea of an event series with Anna Galluccio, the Italian embassy’s scientific attaché in Ottawa. After months of planning and generous support from various sponsors and donors, Cinquecento began on March 22, 2019 with Diluvio, an exhibition of wire-mesh sculptures created by Carleton students who were inspired by Leonardo’s notebooks.

Leonardo’s 567th birthday celebration at Dominion-Chalmers on April 15 was considered the official launch. It was followed by a host of lectures on topics ranging from his sexuality, the long-lost painting Salvator Mundi, the influence of his Christian worldview on his life’s work, and his skilled use of advanced painting techniques to create seemingly three-dimensional imagery in his two-dimensional art.

Mingarelli hosted two prominent da Vinci scholars at Carleton. Martin Kemp, professor emeritus of the History of Art at Oxford University, and Domenico Laurenza, a professor from the Department of Philosophy at the University of Florence, both lectured on campus in November.

The Renaissance man known primarily as an artist, inventor and engineer was also a composer, a theatre costume designer, a choreographer and a talented cook, said Mingarelli. He designed bells, an automatic drum and the instrument known as the viola organist. He even wrote sheet music, some of which was played for the audience.

“This is the impact of Leonardo’s science on his art,” said Mingarelli. “Not only in the visual sense, but also in the more general sense of an artistic form, like dancing, theatre, music. Leonardo contributed to each of those areas.”

Da Vinci has long been considered a genius. Thanks to Cinquecento, his complex and human facets became more widely known.

What he accomplished in 67 years was all the more remarkable as he was born illegitimately, was believed to be gay and was never formally educated.

“Think about what he gave to the world, with all these drawbacks he would have had living in 15th century Italy,” said Mingarelli. “It doesn’t matter who you are or what you are. You need to believe in yourself, do the best you can and not ask how to do it. You just do it.”

Monday, December 16, 2019 in Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Faculty of Science

Share: Twitter, Facebook