By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Rob Lloyd

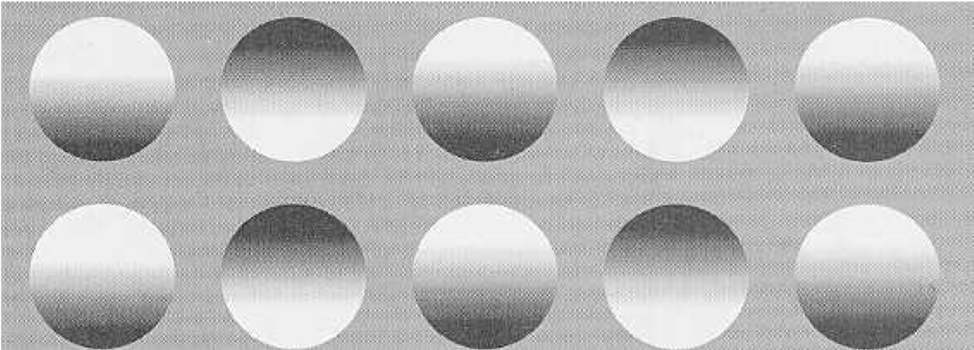

When we look at a black-and-white image of several outlined circles with varying degrees and placement of shading inside their rings, some of the circles will look like bumps, while others will look like holes, despite the fact that they’re on a flat piece of paper.

Image bv V.S. Ramachandran

That’s because we assume that light comes from above and use shadows to interpret 3D shapes and depth.

“The brain has learned that light comes from above, because for millions of years the sun has come from above,” Carleton University President Benoit-Antoine Bacon said during “da Vinci’s Vision: The Beauty (and Limitations) of Painting a 3D World,” a lecture he gave on May 8, 2019 as part of the university’s year-long series of events to explore lesser-known aspects of Leonardo da Vinci’s life.

Cultural and Artistic Flourishing

Carleton’s da Vinci celebration — marking the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death — has been dubbed “Cinquecento,” an Italian term for the cultural and artistic flourishing of the 16th century.

Thanks to his understanding of science and engineering, da Vinci knew how to use shadows, as well as techniques such as occlusion, familiar and relative height, atmospheric perspective and linear perspective to bring depth to his paintings, said Bacon, whose talk drew from his background in cognitive neuroscience research. He focused on the links between brain activity and perception in the visual and auditory systems, as well as on multi-sensory integration.

“The magnificent paintings of Leonardo da Vinci and other artists of the Renaissance are characterized by a dramatic increase in realism and in particular by their remarkably vivid 3D representation of the world,” declared Bacon’s abstract. “Indeed, whereas pre-Renaissance art was iconographic and ‘flat,’ a number of techniques increasingly brought 3D accuracy and fullness to paintings.”

Showing a slide of da Vinci’s “The Mona Lisa” on the screen in the Health Sciences Building’s large lecture hall, Bacon pointed out the artist’s use of shadows “highlighting the roundness of the face and framing that famous smile.”

Da Vinci Harnessed the Emerging Pictorial Techniques of His Era

The hour-long, three-part lecture, which explored how da Vinci harnessed the emerging pictorial techniques of his era “to create art of stunning 3D realism and everlasting beauty,” stressed how he realized the limitations of depicting a 3D world on a 2D canvas and knew that our two-eye viewpoint was the key to those limitations. Bacon ended with a discussion about “the emerging notion that both his artistic mastery and his inability to fully grasp the power of stereoscopic vision . . . might have been due to his having a mild eye misalignment called exotropia, a form of strabismus.”

Strabismus may have helped his art,” said Bacon’s summary slide, “but it is possible that it prevented him from understanding stereopsis” — which is defined as depth perception or 3D vision produced by the fusion of binocular images.”

But that’s excusable, noted Bacon. It took humanity another 300 years to figure this out.