By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Justin Tang

When Kathy Dobson was working toward a master’s degree in Communication Studies at a university in southwestern Ontario, one of her professors said that only five people on the planet read his very specialized research papers.

“If you changed a few words,” she asked him, “do you think you might get 10 readers?”

“He didn’t laugh,” reports Dobson, an instructor, journalist, author and PhD candidate at Carleton University whose research and non-academic writing revolve around media representations of poverty and her own first-hand experiences of living in poverty respectively.

“I’m a writer,” she says. “I want to be read.

“It’s important for me to be doing both academic and non-academic writing,” continues Dobson, whose second non-fiction book, Punching and Kicking: Leaving Canada’s Toughest Neighbourhood, was to launch at a Carleton event. “It’s healthy to have your feet in the real world while doing academia.

“Mind you, if I wasn’t doing all this other stuff, I’d probably have my PhD finished by now.”

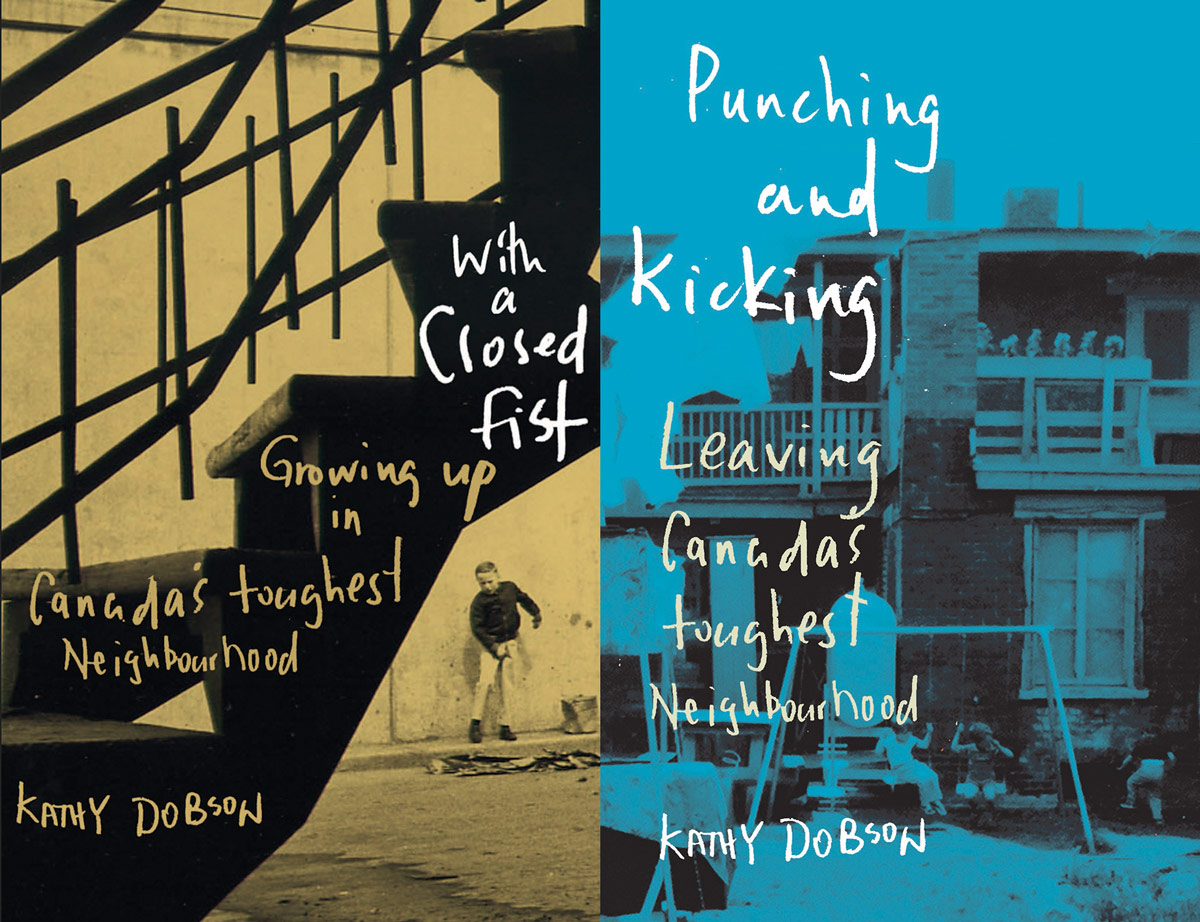

By “other stuff,” she means transforming her first memoir — With a Closed Fist: Growing Up in Canada’s Toughest Neighbourhood — into a script for a producer who plans to make it into a feature film. And writing a collection of short stories. And working on a third non-fiction book, about whistleblowers, for Montreal’s Véhicule Press, which has published both of her previous releases. And teaching Media and Poverty, a new fourth-year, special-topic Communications course at Carleton this semester.

The young Kathy Dobson who narrates Punching and Kicking could never have imagined herself standing in front of a room full of university students. Which illustrates one of the main themes of her research and storytelling: that media and mainstream society make assumptions about people living in poverty and other marginalized communities without a deeper understanding of the systemic problems — and people — at the heart of these issues.

Kathy Dobson Paints a Nuanced Picture of Life Below the Poverty Line

Growing up with a single mother in Montreal’s Point St. Charles in the 1970s, Dobson and her five sisters experience more than their share of hardship, from slum landlords and “pervy uncles” to the prejudices they encounter outside the neighbourhood.

But Dobson infuses Punching and Kicking with dark humour, whether describing her tentative first steps into post-secondary education at Dawson College — “a new environment where problems aren’t solved by a good punch to the head” — or the abortion process at a hospital, where women who can’t afford to pay for the procedure at a private clinic must endure a screening panel of three men before being approved as patients.

The book paints an intimate and nuanced picture of life below the poverty line, revealing the individuals behind the stereotypes and statistics, and challenging, as Erin MacLeod writes in the Montreal Review of Books, “any simple narratives one might have about what it means to be poor.”

Kathy Dobson

Dobson didn’t plan to write a sequel after releasing With a Closed Fist in 2011. But the book received tremendous feedback — the Globe and Mail called it a “wicked, incisive, brutal memoir” — and readers kept asking when she was going to share more of her story.

With a Closed Fist ends on an optimistic note, although far from “happily ever after,” and the same feeling flows through Punching and Kicking.

More Interesting Reads

“It’s never a straight line out of poverty,” says Dobson, who worked as a journalist at CBC and other media outlets for 20 years before going to graduate school, eventually landing at Carleton and securing the support of a prestigious Vanier Scholarship.

“If you grow up on welfare, that has a legacy that will follow you for your entire life in so many ways.”

Punching and Kicking is not writing for catharsis, by any means. The book, in a sense, is “for the people who are still trapped there,” says Dobson.

“All sorts of causes contribute to poverty, and it’s not ‘strength of character’ that allows you to escape,” she says. “That’s one of the things I hope people get out of the book.”

And when they approach her at readings, in tears, saying that the book makes them feel less shame about their lives, that makes all the work worth it.

Insights and Thoughtful Reactions from Students

Dobson strives to bring the same insightful honesty to her teaching and research at Carleton.

She’s been impressed by the “brilliant,” receptive and enthusiastic 30-plus students in her COMS 4800A Media and Poverty class, most of whom she believes “totally get it” — “it” being a critical perspective on representations of poverty in social media and popular culture.

“I’m learning so much from reading their papers and watching their presentations,” Dobson says.

“They’re filled with insights and such thoughtful reactions to what they’re learning.”

She’s also making progress on her PhD dissertation, which she hopes to defend by next summer. Supervised by Prof. Sheryl Hamilton, it’s investigating the idea of “delegated governance” — in this case, government agencies working with private-sector partners to test new technologies and methods on people who live in poverty before possible wider roll-outs.

Prof. Sheryl Hamilton. Photo by Luther Caverly.

This outsourcing of public services, such as social welfare programs, is meant to “maximize efficiency both fiscally and in the delivery of services,” says Dobson. But she’s concerned about digital surveillance and the collection of personal information, about a lack of transparency and accountability, and the impacts on vulnerable citizens.

“If you say, ‘I have nothing to hide,’ then you’re probably white and middle class,” she says.

“I may look middle class, but if you piss me off, Point St. Charles comes out. And I think that’s something that’s missing in academia: more representation of people from different socio-economic backgrounds.”

Thursday, November 29, 2018 in Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs, Faculty of Public and Global Affairs, Journalism and Communication

Share: Twitter, Facebook