By Ty Burke

Humans have been shaped by our environments, and now, we shape them in return. It’s not just that we intentionally alter landscapes, or that our emissions impact the air.

By-products of human civilization are becoming part of the Earth itself. The chemical signatures of industry have created a new unit of geologic time. Radiation and emissions are integrating into the planet’s soils, sediments and rocks.

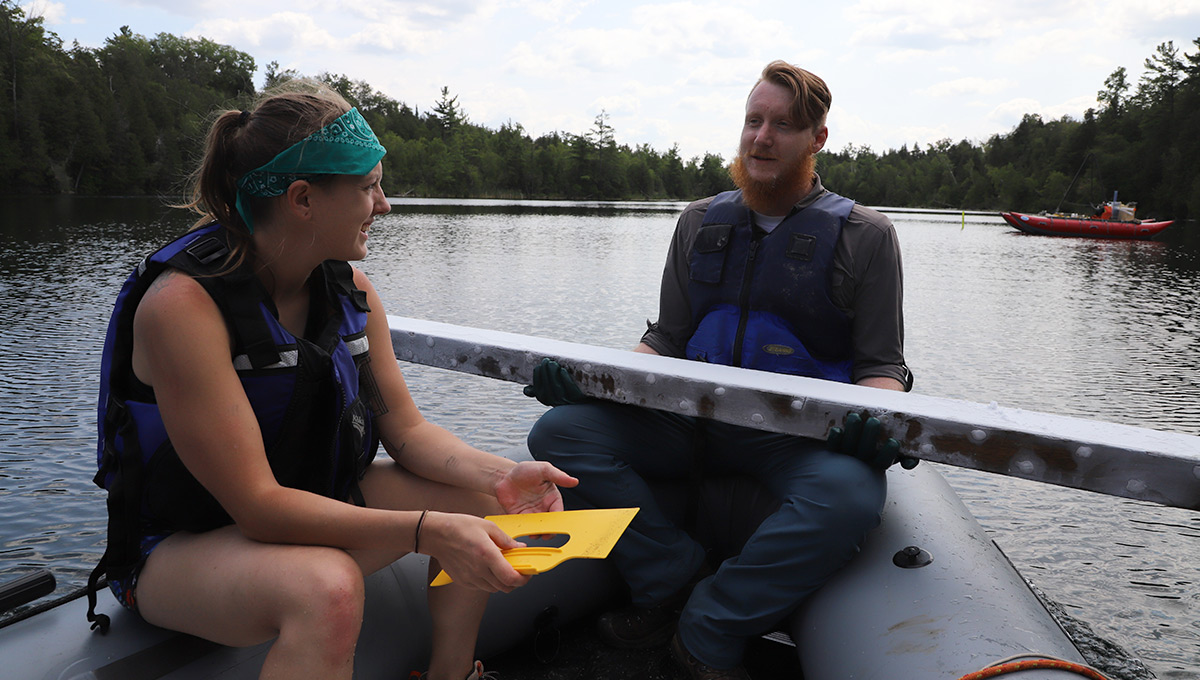

The research team puts a boat in the water at Crawford Lake.

But that’s not exactly new. In Roman times, lead smelting emissions were blowing across the Atlantic and into the geological record of Canada’s north. The Industrial Revolution upped the ante, and by the time widespread nuclear testing rolled out in 1950, trace amounts radiation were dusting the entire planet.

Geologists call this age the Anthropocene – the age of humans. In a discipline where time is often measured in millions or billions of years, they trace its origins to 1950, barely long enough ago to qualify for a seniors discount.

Hunting for the Anthropocene’s

Origins in Crawford Lake

Carleton’s Tim Patterson is helping pinpoint the Anthropocene’s origins. At the International Union for Quaternary Research conference in Dublin, Ireland next July, the Professor of Geology will make the case that Ontario’s Crawford Lake should be the Global Boundary Strategy Section and Type for this new era.

“In the vernacular, it’s called a golden spike,” Patterson says, “a place you can put your finger on, and say that it’s the boundary between one geologic unit and the next. A clear, identifiable point that marks the end of one era, and the beginning of the next.”

But what makes Crawford Lake so special?

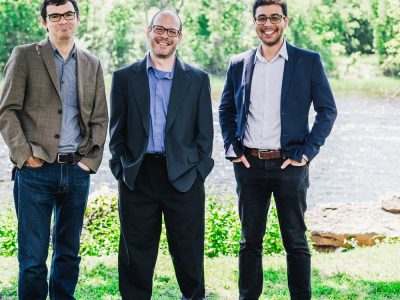

Researchers at Crawford Lake in Milton, Ontario.

It’s tucked in a basin in Milton, Ontario, and protected by a conservation area. The lake bottom is anoxic – it has no oxygen — and as a result, no life. Motorized boats aren’t allowed on Crawford Lake either, further reducing the chances its geology will be disturbed.

“The lake has steep sides, and the wind has difficulty getting in,” says Patterson.

“On most lakes, once the temperature gets down to about 4°C, the temperature in the upper part of the lake matches the temperature in the lower part, and wind comes along and turns the whole thing over. That keeps lakes oxygenated, and organisms can live on the lake bottom. Crawford Lake is very still, and doesn’t turn over. With no oxygen, there’s nothing crawling around to disturb the mud. Anything that falls down lands and stays there, leaving a record of productivity. As a result, you can collect a perfect sedimentary record. You just count backwards to 1950.”

Environmental Signals Key to Finding Golden Spike

Patterson’s lab specializes in freeze cores, flat-faced metal tubes filled with dry ice and alcohol, and sunk into the bottom. The sediment freezes to the core.

“You see and can count all of the lake’s annually deposited layers. We’ll be looking for various sorts of environmental signals: industrial spherules spewed from smokestacks and dumped over the landscape, the radioactive signal, changes in microfossils. We’ll be dating cores using radiometric techniques — creating a comprehensive record built around providing corroborative evidence for that radioactive signal we’ll see at 1950.”

Researchers work on freeze cores pulled from Crawford Lake.

Patterson has been undertaking this research with Brock’s Francine McCarthy and McMaster’s Eduard Reinhardt. Next summer, they’ll present their findings to a commission tasked with choosing the Anthropocene’s golden spike at the conference in Dublin.

Patterson likes their chances.

“It’s a really strong candidate to be designated as the golden spike. A vast number of other candidates can’t be dated as precisely and aren’t in conservation areas. It would really be a coup for our universities and Canada to have the Anthropocene golden spike designated at Crawford Lake. There just aren’t many geologic units, so that honour…it would be very special.”

Friday, October 26, 2018 in Faculty of Science, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook