By Matt Gergyek

Photos by Chris Roussakis

The history of mental illness is a dark and fragmented one.

“You can go to asylums in the United States and they’ve got graveyards” made up of “rows and rows of . . . these little white crosses and stones,” says Carleton Prof. James Miller, who teaches and researches the history of mental illness. “These people don’t even have names; you have no idea who they are.”

While the history of mental illness is tragic and brutal, Miller looks at it from an empathetic perspective to try to understand the individuals caught up in shifting understandings of the causes and treatments of madness over the centuries.

“It’s not just about the guy who invented the lobotomy, it’s about the people who underwent the lobotomy,” he says.

Miller first became interested in research and teaching about “mad studies” (the name comes from the mad pride movement – in some respects similar to the queer pride movement which involves “reclaiming the label and taking it back as a positive”) when he was introduced to the genre of “outsider art.”

Outsider art is artwork created by untaught artists, often only discovered and highlighted after their deaths. Artwork created by asylum patients is an especially popular form of outsider art.

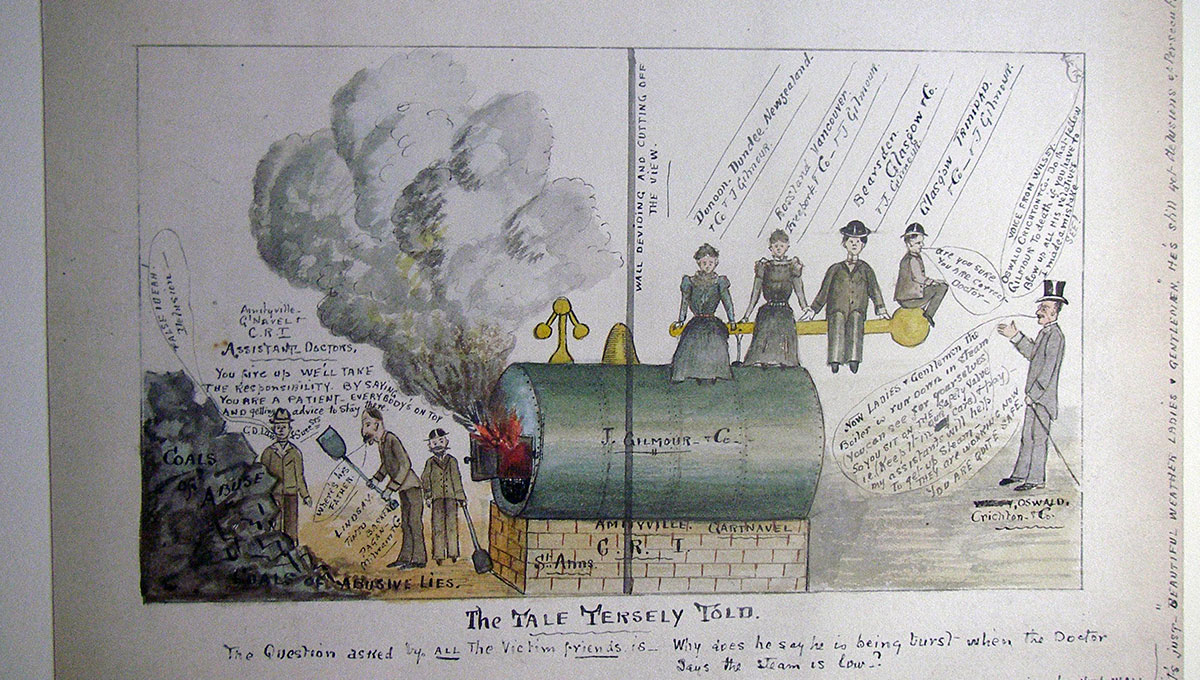

The Tale Tersely Told

One of Miller’s favourite pieces of asylum artwork is The Tale Tersely Told by John Gilmour. A bookkeeper turned sugar trader, Gilmour spent more than 10 years in various asylums internationally, but his longest stay was at Crichton Royal Institute in Dumfries, Scotland. The artwork Gilmour created there opens a window into his life inside the asylum.

“I love the fact that these people are in far more desperate conditions than I’ll ever experience but they’re compelled to create something,” Miller says.

“We’ll always have these artworks these people created. I think so often there’s no voices for the mad . . . so these artworks speak for them in a very powerful way.”

The Tale Tersely Told shows Gilmour and other asylum patients sitting on the safety valve of a steam boiler, questioning their doctor’s actions.

“He created these drawings to express his belief that he was being tortured and oppressed by the asylum superintendents and staff, while his relatives were being lied to about his condition,” Miller says.

Struggling with Mental Illness

His research and teachings come from a powerfully personal place- Miller has struggled with a mental illness of his own.

“I’ve dealt with pretty severe depression on and off since I was a teenager,” he says. “The key for me is not seeing it as your whole personality. We never talk about people as being a cancer, it’s a person with cancer. It’s a facet of you, it’s not an all consuming characteristic. I think that’s one of the things I try and get across in class, the complexity and diversity of experience.”

Miller’s research and personal experiences led him to develop the third-year history course called Madness in Modern Times, which launched three years ago.

“At the time, I was questioning the value of lecture formats,” Miller says, so the course is taught completely online, created in collaboration with Carleton’s Education Development Centre (EDC). Miller especially credits the instructional designers at the EDC.

“Historians always say they’ll focus on a certain period of time but then they start way earlier than that,” Miller says.

The course begins by examining ancient perspectives on the causes of mental illness, when the humoral theory of illness was popular. The theory argues the human body is composed of four major fluids, each with a pair of two possible opposing impacts on the body: blood (hot and wet), phlegm (cold and wet), yellow bile (hot and dry) and black bile (cold and dry). Mental health issues were believed to be primarily caused by an imbalance of these fluids in the body.

“Starting this far into the past establishes how long humans have been experiencing these conditions and asking questions about their causes,” Miller says.

Treating Madness: The Rise of Psychiatry

The course then turns towards 17th and 18th century understandings of mental illness, which attributed causes to a frayed or dysfunctional nervous system.

From there, Miller turns to the rise of the asylum in the late 1700s and early 1800s. According to Miller, the movement began with good intentions.

“Madness is seen as a loss of reason and in this sense if you put people in institutions and treat them well and treat them rationally, that will help to restore their reason,” he says of the rationale.

Yet due to overcrowding and underfunding, conditions in asylums and standards of living for patients quickly took a nosedive, Miller says.

“Asylums became more about protecting society from people presumed to be dangerous than actually helping [these people].”

Miller then explores the rise of psychiatry in the early 1900s, accompanied by the use of the notorious lobotomy procedure (which, believe it or not, won its creator a Nobel Peace Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1949) and electroconvulsive therapy.

Finally, the course turns to the current reality, where both mental illness and pharmaceutical treatment are extremely common.

Patient Experience

Only about one in 20 Canadians took any kind of psychiatric drug in 2002, according to a study published in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry in 2015. In 2016, more than one in five Canadians took an antidepressant, just one kind of psychiatric medication, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

“Medications are a much more accepted form of treatment and they’re seen as non-invasive, even if they are powerful drugs that are altering your brain in ways that nobody fully understands,” he says.

A strong thread wove throughout the course is patient experience, Miller says.

“I think when you’re dealing with something as personal as mental illness it’s harder to get at the individual experience, but you’re still obligated to try. You’ve got to try and put yourself in the other person’s shoes.”

As mental illness becomes more prominent, people should take the time to get educated about it, he argues.

“You’ve got to look at the big picture but you can’t lose sight of the fact that the big picture’s made up of all sorts of individuals, all whose experiences are valuable and important, even the one’s we’ll never know anything about.”

Ultimately, Miller says he hopes the course helps students empathize with people struggling with mental illness.

“I remember one student said: ‘This is a history of my people.’ . . . That’s one of the sweetest things anyone’s ever said to me.”

Tuesday, October 23, 2018 in Health, History, Mental Health

Share: Twitter, Facebook