By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

Higher education, like much of the world, has entered a period of rapid change.

Traditional approaches to teaching and research need to evolve to better equip students and professors with the tools they need to tackle the planet’s most pressing problems.

As part of this shift, individual faculties and departments at every university must examine how they operate and how they can become more effective.

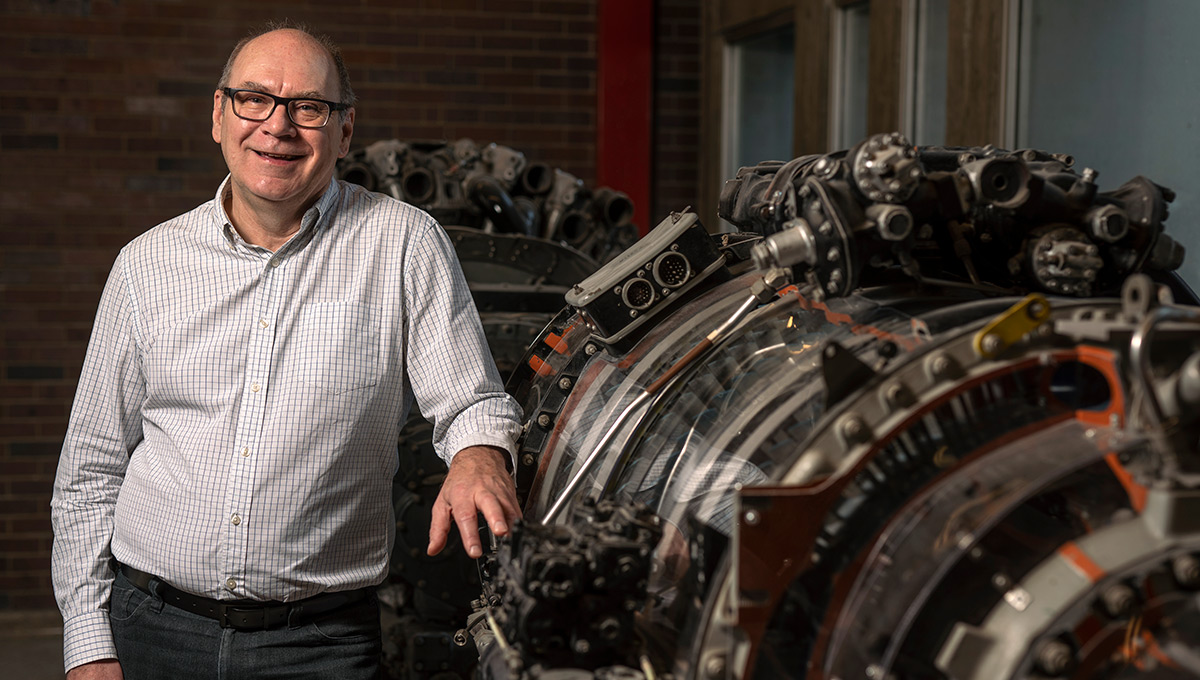

Larry Kostiuk, Dean of Faculty of Engineering and Design. Photo: Future Energy Systems

At Carleton University, the Faculty of Engineering and Design’s new dean, Larry Kostiuk, is prepared to take on this challenge — and he’s hopeful about all of the new directions and discoveries that could emerge.

“Historically, universities haven’t been structured around the stress points of society,” says Kostiuk, who began his five-year term on July 1 after more than 25 years in a series of increasingly senior roles at the University of Alberta.

“Typically, we were organized around a set of processes and principles. But our society is facing some serious issues and the old model — the expectation that there’s somebody off campus, such as government or the private sector that assembles the knowledge we create into something more useful and tangible — doesn’t hold anymore.

“Because the world is changing, more ‘self-assembly’ is expected on campuses. Universities see needs, demands and challenges, and we can put together teams and choreograph our activities to take on these big problems. The world has lost patience with the old model.”

How this transformation will continue to roll out at Carleton remains a question — or, rather, an array of questions, as dozens and dozens of critical conversations take place in the months and years ahead.

But Kostiuk, who has only been on the job for a few weeks and is still in the process of meeting his new colleagues and collaborators, is eager to dive in. Even, perhaps especially, if that means venturing into new territory.

At Carleton, for example, the “Design” component of the Faculty of Engineering and Design (FED) blends in disciplines, such as architecture and urban planning, that aren’t a natural fit for people like him with a pure engineering background.

Kostiuk sees this as a chance to elevate his understanding, to bring ideas together in an interdisciplinary way, to mesh hard physical sciences with diverse ways of thinking — and to take a head-on, holistic run at wicked problems, including climate change, that we must strive collectively to address.

The Importance of Interdisciplinarity

Kostiuk got a key lesson about interdisciplinarity while he was still a young researcher.

He was born in Hay River, N.W.T., where at around age five he started tinkering with cars and heavy equipment at the gas station and construction company run by his dad. (“My father had no sense of boundaries,” he says.)

The family eventually moved to Calgary and Kostiuk followed his older brother into the mechanical engineering program at the University of Calgary before completing a master’s in engineering at UAlberta and then a PhD at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

In 1988, while working toward his doctorate, with a research focus on combustion, Kostiuk attended a conference and unexpectedly found himself at a presentation exploring why the world was running short on food.

Because he didn’t have an aisle seat, he couldn’t walk out of this session that seemed completely unrelated to his studies. Stuck, he sat and listened and learned a lot about nitrogen chemistry, which it turns out is important to both food production and combustion.

His conclusion?

“You’ve got to put all of the pieces together,” says Kostiuk.

“You need to look upwind and downwind from the area you work in. Who does the knowledge you develop get passed to? Who do you need information from? What does that chain look like?

“It’s not about technology pushing and society responding,” he continues. “It’s about making a conscious collective choice, and having more eyes and voices at the inception point of research projects and sharing the steering wheel at the early stages.

“The best future for our Faculty of Engineering and Design is one where we’re right in the mix with everybody else. With other faculties, departments and schools, and with the communities with which we engage. We all need to be part of the solution.”

Transitioning to Energy Sustainability

At UAlberta, Kostiuk served as chair of the Department of Mechanical Engineering from 2002 to 2012 and as associate vice-president of Research from 2015 to 2018.

During the last two years of the latter role, he was also the director of Future Energy Systems, which was launched in 2016 with $75 million from the federal government’s Canada First Research Excellence Fund to help the country transition to a low net-carbon energy economy.

According to the Future Energy Systems website, the program focuses on “multidisciplinary research that develops the energy technologies of the near future, integrates them into today’s infrastructure, and examines possible consequences for our society, economy and environment.”

“People expect to live and work in an environment that’s different from what nature provides,” says Kostiuk.

“Humans depend on built environments. We often want to be slightly warmer or slightly cooler, and doing that takes a lot of energy. Given the population of the planet, there are massive challenges around energy sustainability. But you can’t get too far in this area without also thinking about air quality and water quality and so many other things.

“This is a global issue with lots of potential solutions, from the agri-food industry to how we build houses and how we move people and goods around. It’s always important to look under the hood and further down the road.

“Most people imagine a future that’s a little bit different than today,” he continues, “but making this transition while society is active and moving and living is non-trivial.”

Now that Kostiuk has left the heart of Canada’s energy industry for the country’s political capital, his role in this transition will likely pivot to include more conversations about policy.

But first and foremost, he’s an engineer — one of the draws of the dean position at Carleton was that it was with an engineering faculty, not in central administration — and he understands that policy decisions have to be driven by reality.

“One of the things that’s intriguing about being in Ottawa is that there’s a strong engineering and science focus here to inform policy discussions,” says Kostiuk, citing both the city’s vibrant educational community and government partners such as the National Research Council, Natural Resources Canada and Health Canada.

“Having a major engineering school like Carleton’s in close proximity to national decision-makers is very important. We are also their suppliers of highly qualified personnel.”

Kostiuk: Keeping His Feet in the Research World

Kostiuk has travelled widely throughout his career in teaching and research, which has explored not only combustion but also thermodynamics, pollutant formation and control, and energy conversion systems.

He has been a visiting professor at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in France (Orleans), Indian Institute of Technology (Roorkee), his PhD alma mater in Cambridge and, in 2014, at Carleton.

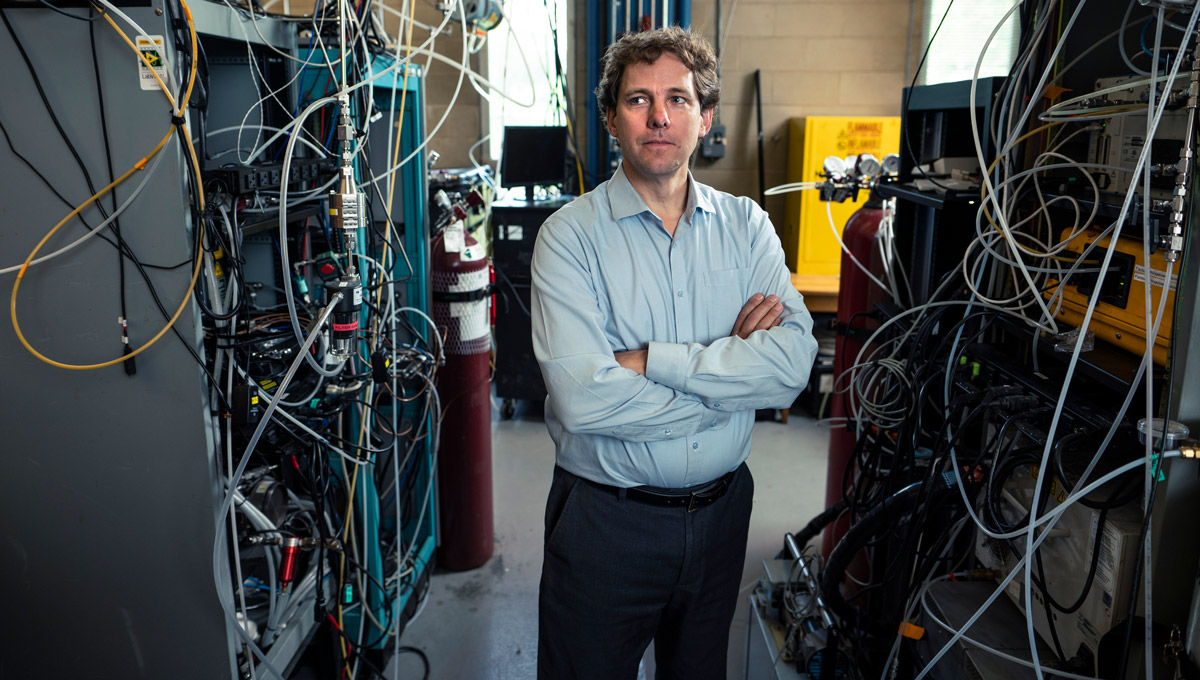

Kostiuk came here for two months primarily to collaborate with Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Prof. Matthew Johnson, who leads the NSERC FlareNet Strategic Network and was Kostiuk’s first PhD student at UAlberta in the mid-1990s.

Prof. Matthew Johnson

Enough time had passed that Kostiuk felt comfortable working with Johnson as peers. They picked up some of the untouched research they had started together in Alberta around flaring and pollutants, asking questions about regional and global implications and about who else cared and might want to team up.

This reprise ultimately led to the start of FlareNet, whose overarching objective is “to provide a quantitative understanding of flare-generated pollutant emissions critical to enabling science-based regulations, accurate pollutant inventories, understandings of climate forcing and health implications, and engineered mitigation strategies to minimize environmental impacts in the energy sector.”

And it put Carleton on Kostiuk’s radar.

As dean, involvement with FlareNet will allow Kostiuk to keep a foot in the research world and help prevent him from becoming disconnected from important teaching relationships.

“I try to remain relevant and maintain a contemporary understanding of what’s happening in classrooms and labs,” he says.

“Knowing what and how a modern undergraduate or graduate student thinks is crucial.”

This insight gives Kostiuk two-way academic street cred. He can understand the challenges faced by colleagues who have concerns about the system, and he can suggest changes that make sense at both the administrative and grassroots level.

It has also given Kostiuk an interesting perspective on experiential learning, which is a key priority at Carleton and other Ontario universities.

Today’s high school students may not be the tinkerers that he was as a teen, but that doesn’t mean university should be all about hands-on skills.

“I don’t see an engineering education as a training process, as something that’s meant to fulfill an employment role,” he says. “Because society has become so technologically advanced, I almost see an engineering degree like a liberal arts degree from the 1960s — foundational knowledge that’ll help you figure out the world we live in.

“I’d like to see people graduate with a set of attributes that give them a sound fundamental framework combined with an intimate understanding of how the world works. They need to be able to investigate issues, to problem solve, to collaborate with partners from all sorts of backgrounds. To do that, we have to nurture the whole person.”

Wednesday, August 21, 2019 in Faculty of Engineering and Design, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook