By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Fangliang Xu and Chris Roussakis

Five years ago, Canada took an important step toward a long-term goal.

On Dec. 15, 2015, after hearing from more than 6,000 witnesses over seven years, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its final report with the warning: “Getting to the truth was hard, but getting to reconciliation will be harder…”

Last May, as part of a movement to support Indigenous learners and bring Indigenous knowledge into classrooms in the wake of the TRC, the Carleton University Strategic Indigenous Initiatives Committee (CUSIIC) released its landmark Kinàmàgawin report.

Kinàmàgawin — which means “learning together” — was the result of an 18-month collaborative process and culminated in 41 Calls to Action addressing community engagement; Indigenous student support; student experience; ways of teaching and learning; culture, systems and structure; research and innovation; and metrics.

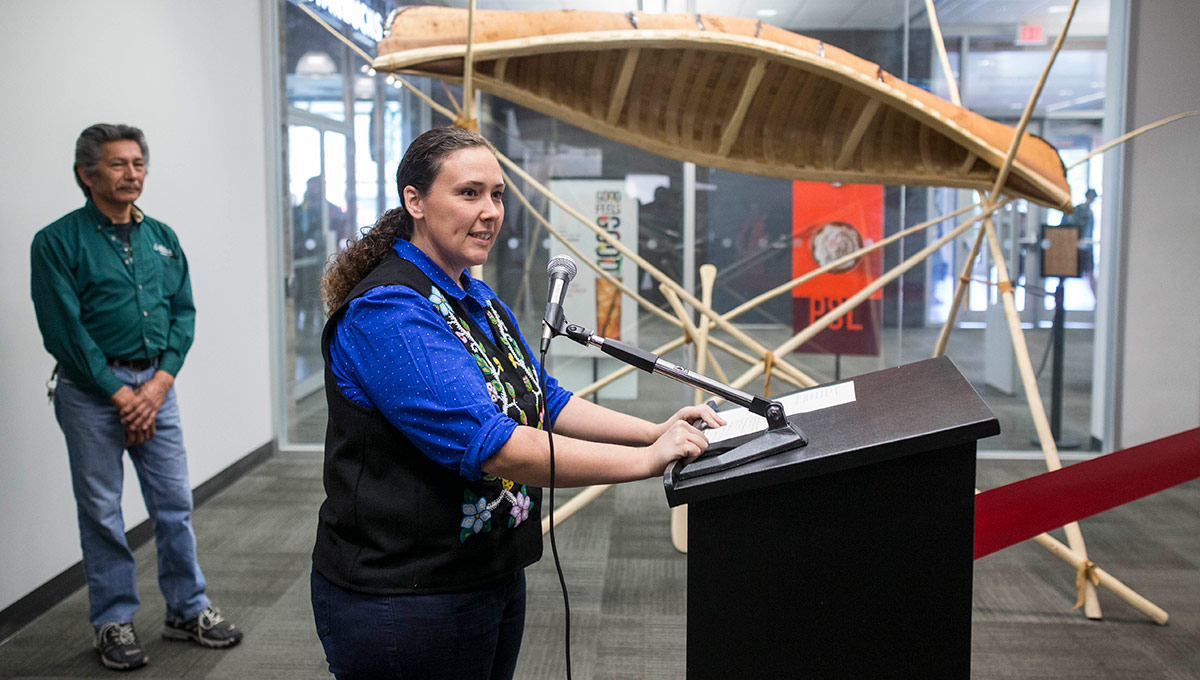

“The ultimate goal of the work we’re all engaged in is to support Indigenous students by creating culturally relevant and resonant experiences in the classroom and in the broader campus community,” says Benny Michaud, director of Carleton’s Centre for Indigenous Initiatives (CII) and one of CUSIIC’s co-chairs, along with Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller from the School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies and Provost and Vice-President (Academic), Jerry Tomberlin.

Centre for Indigenous Initiatives Director Benny Michaud

“Relationships are at the centre of the work that we do, and having good relations — or miyo-wichitewan in Cree/Michif — means being able to share truths, even when those truths cause our hearts to ache,” says Michaud. “Achieving a relationship where both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people can rely on a shared set of truths is necessary for reconciliation to occur.

“The vast majority of Canadians are still learning about the historic and ongoing impact of settler colonialism on Indigenous communities. The act of reconciling is difficult for everyone. One group must reconcile the trauma they have experienced, while the other must reconcile how that inflicted trauma has benefited them. It’s a journey that is both deeply personal and extraordinarily necessary.”

President Benoit-Antoine Bacon at the Indigenous Learning Bundles launch in 2018

“With the TRC report already five years out, we must make sure to keep up the momentum in deepening the understanding of Indigenous worldviews and implementing Indigenous initiatives throughout the Carleton community,” said President Benoit-Antoine Bacon.

“Our new Strategic integrated Plan and, of course, the Kinàmàgawin report provide a clear road map to continuous improvements and measurable outcomes, and I am encouraged by our progress so far.”

On the anniversary of the TRC report, at the end of challenging year that has heightened the significance of the Kinàmàgawin recommendations, we look at the progress achieved so far at Carleton and some of the work that remains on the long journey ahead.

Hiring Indigenous Faculty and Staff

One of Kinàmàgawin’s Calls to Action addresses the need to increase the number of Indigenous employees at Carleton, “supported by the development of Indigenous hiring policies for Indigenous-specific faculty and staff positions.”

In January 2019, the university announced a plan to hire 10 new tenure-track Indigenous professors over the ensuing two years — a process that is now nearing completion.

An Indigenous faculty member has joined the Department of Electronics, for example, and several units — such as the Sociology and Social Work departments — are preparing to conduct interviews in the new year.

Several new Indigenous staff members have also started at Carleton, including two Indigenous cultural counsellors, an Indigenous programs officer, an Indigenous Enrichment Support Program co-ordinator, and the new position of Algonquin Liaison Officer with the CII — a unique role in the province that sets Carleton apart in its commitment to nurturing and deepening relationships with the university’s host communities.

Phillip Macho Commonda, Algonquin Community Liaison Officer

“Having a person delegated to building relationships with the area’s Algonquin communities is vital because Ottawa and Carleton sit on unceded traditional Algonquin land,” says Liaison Officer Phillip Macho Commonda, a member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishnabeg First Nation near Maniwaki, Que.

“This position allows for Carleton to not only respect the land it sits on but also fosters active input from the surrounding communities.”

Commonda sees progress on Kinàmàgawin’s Calls to Action as a sign that Carleton is moving forward in partnership with Indigenous communities toward a stronger relationship — a relationship, he says, “where Indigenous people feel they are not only heard, but also a part of a growing movement for equal rights.”

Learning Bundles Used in More Than 50 Courses

Although Carleton’s unique Collaborative Indigenous Learning Bundles predate the release of Kinàmàgawin, the projects speak directly to Carleton’s Call to Action No. 21: “The development of appropriate measures to ensure that every student graduating from Carleton achieves basic learning outcomes with regards to Indigenous history and culture.”

Creation of the Bundles — a series of focused Indigenous knowledge modules available online for faculty members to deliver in their classes — were developed by Horn-Miller and her colleagues to serve as a resource for instructors and a learning tool for students to provide the factual and theoretical basis for understanding Indigenous history and politics in Canada, while prompting students to consider how this knowledge might be applied in their areas of study.

Today, says Horn-Miller, the Bundles have been used in more than 50 courses, with more than 2,000 students in the fall 2020 term engaging with them. Two new Bundles have been completed recently.

Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller

The CII is also developing a four-part module training for faculty, staff and students which explores anti-Indigenous racism in Canada, unconscious bias, privilege, practising allyship and reconciling state-sponsored violence towards Indigenous peoples.

And Michaud, the CII’s director, teaches the only course at Carleton focused on Métis history, culture and kinship systems — a history class that will soon be evolving into a new course within the School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies.

“It’s significant because it’s the only course like it and also because most Canadians know very little about Métis people and the Métis Nation,” she says.

“Recognizing the diversity of Indigenous peoples means having courses that include those diverse worldviews, and the Métis worldview is extremely unique.”

Moreover, Kinàmàgawin Call to Action No. 31 is for the “establishment of an Institute for Indigenous Research with the intent of continuing, consolidating and further promoting innovative and collaborative research pertaining to Indigenous peoples, communities and nations,” and Horn-Miller expects the new institute to be announced in the new year.

Indigenous Representation and Voting Rights

In Kinàmàgawin’s section on culture, system and structure, one recommendation is for Indigenous representation, with full voting rights, on the university’s Board of Governors and in the Senate.

The board’s membership currently includes Waneek Horn-Miller, a Carleton Political Science graduate, motivational speaker, television host and former member of the national women’s water polo team — the first Mohawk woman in Canada to compete in the Olympics. She joined the board for a three-year term in September 2020.

Waneek Horn-Miller

Prior to Horn-Miller, Peter Dinsdale — the president and CEO of YMCA Canada and former CEO of the Assembly of First Nations — was on the Board for several years and was a strong advocate for creating an Indigenous strategy at Carleton.

Meanwhile, the Senate — Carleton’s most senior academic body — has officially expressed support for Kinàmàgawin and will encourage Indigenous faculty and students to apply for vacant positions when it releases its next call for nominations in the new year.

This past September, Carleton and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyak Dun in the Yukon signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to collaborate on Indigenous and northern studies, post-secondary education, research and access for learners.

The partnership — an initial seven-year term with the possibility of renewal — will draw on both traditional Indigenous knowledge and non-Indigenous knowledge to inform and enrich research and teaching. Projects will be designed by and attributed to both parties, the type of shared journey that is at the heart of Kinàmàgawin.

Pamela Palmater speaks at the Kinàmàgawin Symposium in Feb. 2020

Coming up on Feb. 25, the CII will host the second annual Kinàmàgawin Symposium that welcomes community members. Registration for the online event opens on Jan. 11, 2021 and the theme this year will be The Inuit Relocations: Intergenerational Impacts and Inuit Resilience.

“The Inuit story is often not given a platform and sometimes Inuit experiences are lumped in with the experiences of other Indigenous peoples,” says Michaud.

“The goal of symposium is to provide learning opportunities on topics that the Carleton community might not otherwise have access to.”

Overall, says Michaud, “there has been exceptional commitment demonstrated at Carleton in the last few years toward bringing Indigenous pedagogies into the university. Not only have there been significant investments in creating Indigenous-specific faculty and staff positions, there has also been an increased platform at Carleton to bring Indigenous perspectives forward.”

Tuesday, December 15, 2020 in Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook