Carleton University’s Tim Patterson is one of the principal investigators of a project at Crawford Lake in Milton, Ontario, where he is studying well-preserved layers of sediment found on the bottom of this deep lake. In pulling and analyzing ice cores, Patterson, alongside researchers at Brock University and a multi-institutional team of experts, has uncovered evidence of the ‘Great Acceleration’ – a period of intense resource use, population growth, and environmental impact in the mid-20th century.

On July 11, the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) announced that out of the 12 sites in consideration worldwide, Crawford Lake was selected as the site that could formally define the start of the Anthropocene – a proposed new epoch shaped by the significant global impacts of recent human activity.

Read more on the groundbreaking research project below.

By Dan Rubinstein

In April of this year, Carleton University environmental geologist Tim Patterson and his research team returned to Crawford Lake, a place now very familiar to them, to extract more “freeze cores” from the lakebed.

The lower reaches of this small, steep-sided, deep lake — located in a conservation area just west of Toronto — are chemically distinct and permanently isolated from the waters above, making it inhospitable to most organisms. The sediments at the bottom thus remain undisturbed, with distinct layers deposited annually.

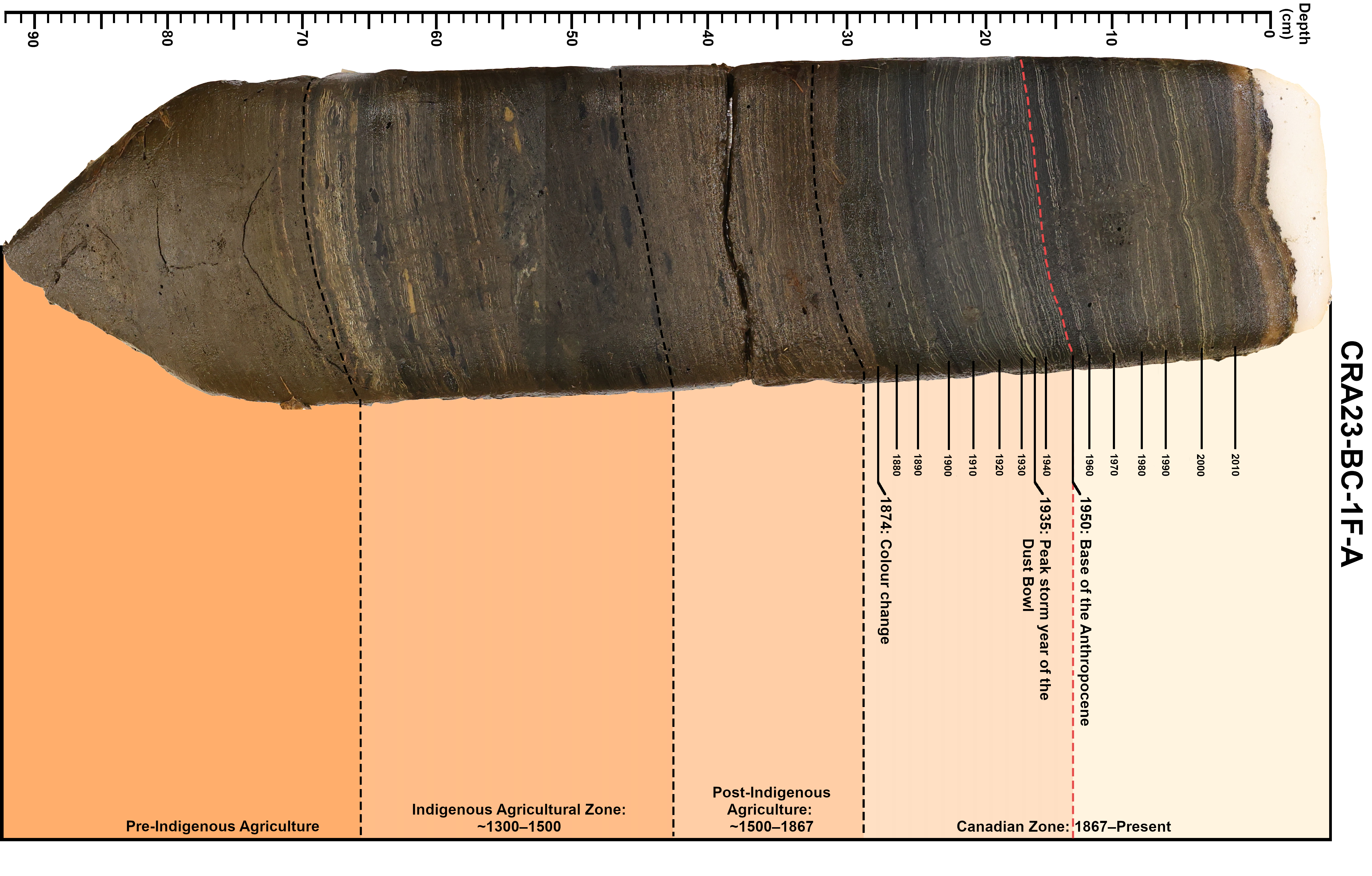

So when Patterson pushed a flat-faced metal rod filled with a slurry of dry ice and alcohol into the lakebed, the sediment that froze to it provided a perfectly preserved tree-ring-like record of industrial emissions, radioactive elements and other chemical signals released into the atmosphere over the years.

Tim Patterson, Professor of Earth Sciences at Carleton University

After being winched out of the lake, these cores, up to two metres tall and 15 centimetres wide, were analyzed by Patterson and his students in their lab at Carleton, as well as by a large team of national and international collaborators, including Indigenous partners.

The data they came up with was a key part of the successful campaign to have Crawford Lake declared the “golden spike” for the Anthropocene — ground zero for the start of a new geological epoch, circa 1950, in which unprecedented human activity has had a significant impact on the planet’s climate and biosphere.

“This is a tremendous opportunity to show people how sensitive our world is to human activity,” says Patterson, who also does freeze core field work to help monitor and safeguard the environmental health of lakes in northern Canada.

“As environmental earth scientists, we’re mostly interested in things that leave a permanent geological record. Crawford Lake archives the key indicators proposed to mark the beginning of the Anthropocene: plutonium isotope peaks associated with nuclear weapons testing, fly ash produced by high-temperature combustion of fossil fuels, and major ecological changes.

“The concept of the Anthropocene has captured the imagination of both the general public and the scientific community. It is a great honour to have the golden spike here in Canada.”

The Anthropocene’s Golden Spike: A Stratigraphic Voting Process

The international process to select a golden spike for the Anthropocene goes back nearly 15 years, when members of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), which operates under the umbrella of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), started to debate whether this is indeed a new geological epoch and, if so, when it began. In 2019, they voted to recommend the middle of the 20th century when soaring human populations, industrial pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as plutonium isotopes from nuclear testing altered the planet’s systems.

In April, the AGW narrowed down the list of golden spike candidates to three and on July 11, they announced that Crawford Lake had been selected as the best geological example of the proposed Anthropocene.

The Patterson Lab team collects cores from the deepest part of Crawford Lake (Photo by Brock University)

The research at Crawford Lake is co-led by Patterson and Brock University’s Francine McCarthy and Martin Head, both members of the AWG. When McCarthy realized she needed a freeze core expert for the project, she contacted Patterson, whom she had met when they were undergraduates together at Dalhousie University.

Patterson has been using freeze cores in his research for around 25 years. They preserve an undisturbed record of paleolimnological change and are more accurate than conventional coring techniques. At Crawford Lake, the Carleton team also looked at the concentration of chrysophytes and diatoms, shelled microorganisms whose populations are very sensitive to agriculture runoff, acid rain and other by-products of human activity.

A freeze core pulled during the April, 2023 expedition by Tim Patterson and his team at Crawford Lake

The lakebed strata, which are at most a couple of millimetres thick per year, provide a treasure trove of information about airborne substances in the local area and further afield. For example, fly ash is abundant in the wake of World War II — in part, says Patterson, from steel plant smokestacks in nearby Hamilton.

A novel photography technique that Patterson and his students have developed allows them to zoom in on these annual layers, which they can associate with specific calendar years. They can do other types of high-resolution analysis as well and only need to rely on an off-campus labs for the plutonium and fly ash testing, which was done for consistency at the same labs in the U.K. for all of the golden spike candidates.

Back in Ottawa, the Canadian Museum of Nature is preparing to archive the Crawford Lake freeze cores in its cryo storage facility, they will help tell the story of Earth’s past — and future.

Tuesday, July 11, 2023 in Faculty of Science, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook