By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

When Angelo Mingarelli was a kid growing up in Montreal, his father, who had immigrated to Canada from Italy and worked as a correspondent for an Italian-language newspaper, would hold court at the dinner table, talking to his sons about art and science and the cornucopia of ideas he was exposed to by his Jesuit and Franciscan teachers.

“My father was a real Renaissance man,” says Mingarelli, a professor in Carleton University’s School of Mathematics and Statistics, “and from a very young age I had a strong sense of who — and how significant — Leonardo da Vinci was.”

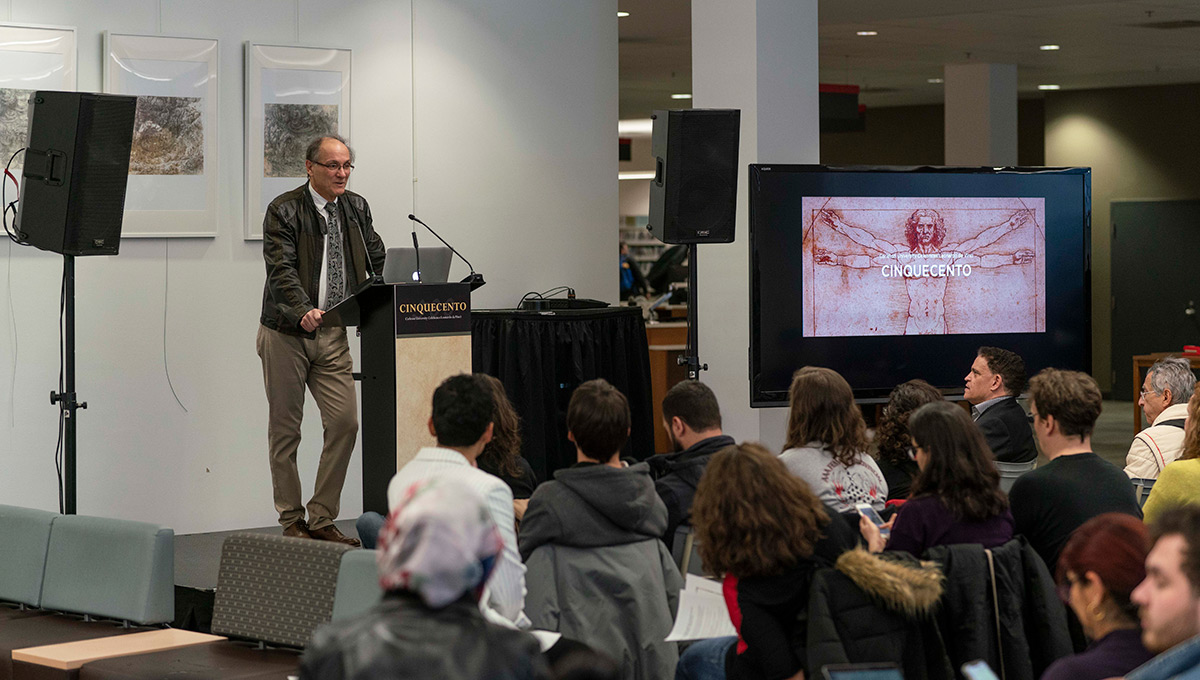

Prof. Angelo Mingarelli

Because 2019 is the 500th anniversary of da Vinci’s death, Carleton has organized a year-long series of events to explore lesser-known aspects of the artist, inventor, scientist and scholar’s life and examine the impact of his achievements on our present day.

And because Mingarelli — probably the most theatrical math prof you’ll ever meet — is so passionate about da Vinci, he was a natural to chair a committee arranging the university-wide festivities known as “Cinquecento,” an Italian term for the cultural and artistic flourishing of the 16th century.

“I started learning about da Vinci and his mystique as a child,” says Mingarelli, who happened to be born in 1952, the 500th anniversary of the original Renaissance man’s birth.

“Eventually that becomes part of you.”

The Leonardo 2019 Committee is Formed

The wheels that led to Cinquecento started spinning three years ago, when Mingarelli had a conversation with Anna Galluccio, the Italian embassy’s scientific attaché in Ottawa.

Although their discussions remained on the back burner for a while, ultimately the Leonardo 2019 committee was formed, and planning snowballed as Mingarelli invited internationally renowned da Vinci scholars to come to Carleton — and, much to his surprise, they accepted.

Those scholars include Martin Kemp, an emeritus research professor in art history at Oxford University and one of the world’s leading experts on da Vinci and the Renaissance and links between art and science, who will deliver the Faculty of Science’s annual Herzberg Lecture on Nov. 21, 2019.

Two months before that, on Sept. 10, best-selling author and historian, Ross King, whose most recent book, Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies, won the 2017 RBC Taylor Prize, will also do a lecture at Carleton.

But people interested in or curious about da Vinci won’t have to wait until next fall.

Diluvio

On May 8, Carleton President Benoit-Antoine Bacon, a neuroscience researcher, will give a talk in the Health Sciences Building called Da Vinci’s Vision: The Beauty (and Limitations) of Painting a 3D World.

And on Monday, April 15 — da Vinci’s birthday — Mingarelli will officially launch Cinquecento with a lecture at the Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre focusing on Leonardo’s life and some of his lesser-known contributions, such as anatomy, astronomy and culinary arts, among others.

The free event begins at 7 p.m. and will include refreshments and highlights from Diluvio, an exhibition of wire-mesh sculptures that draw inspiration from da Vinci’s Diluvio drawings.

Diluvio, which opened last month and will remain on display in the lobby of the MacOdrum Library until April 30, means “deluge,” and the Diluvio drawings sketch out the dynamic properties of air and water in motion, channelled through the power of cataclysmic storms.

“There are sections in Leonardo’s notebooks where he absolutely praises nature’s creativity,” says Prof. Manuel Báez of Carleton’s Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism, whose students created the sculptures.

“He was moved by that to declare a clear, profound distinction between mathematics as conceived by mankind and the mathematics of nature.”

Da Vinci’s Life Outside Art and Engineering

The Mona Lisa is probably da Vinci’s most famous painting, although the most expensive painting even sold — Salvator Mundi, which went for more than US $450 million at auction in 2017 — is also believed to be a long-lost Leonardo masterpiece.

But regardless of these superlatives, Mingarelli is more interested in da Vinci’s life outside art and engineering.

“It was a very big life,” Mingarelli says, talking excitedly about da Vinci’s uncanny ability to draw extremely accurate two-dimensional representations of 3D objects and map human anatomy freehand despite being neither a mathematician nor a medical doctor.

“He was basically a brain for hire,” he continues, noting how da Vinci built bridges and designed fortresses, and how just 7,200 pages of his work are held by archives, galleries and museums, with another 30,000 or so pages unaccounted for.

Prof. Manuel Báez

“He was the greatest genius ever. What else could he have done?”

Mingarelli is perpetually amazed by da Vinci’s capacity for bringing together the technical and creative. This link is something he tries to emulate in his own work as a math professor, in areas such as “celestial mechanics” and “fuzzy cellular automata,” and he believes that the capacity to make connections between seemingly disparate ideas can also help students better understand and tackle society’s major challenges.

“Like my dad always said: ‘The more you know, the better off you are,’ because you can draw links between things that were previously unconnected,” says Mingarelli.

“We have to extend our imaginations outside our own realms so we can find other applications for the work that we do.

“Leonardo knew so much,” adds Mingarelli. “He studied so much. He just wanted to know — and nothing stopped him.”

Tuesday, April 9, 2019 in Faculty of Engineering and Design, Faculty of Science

Share: Twitter, Facebook