Lead image courtesy of Amanda Cotton

By Jena Lynde-Smith

Shane Gero‘s family is bigger than most. He has his immediate family, made up of his wife and three sons, his extended family, and his whale family – a group of around 400 sperm whales that reside in the Eastern Caribbean Sea.

On July 8, the whale family welcomed a new calf to their pod, an event that will go down in history as the first ever filmed and recorded sperm whale birth. Gero, a scientist-in-residence in Carleton University’s Department of Biology, was leading the crew that witnessed it.

“I felt so happy for them (the whales) in that moment,” Gero recalls. “It was so galvanizing to witness, especially alongside all these people from different places and disciplines. We all felt the extreme weight of that day.”

Where it Began

Gero has been researching this particular family of whales for almost 20 years. His fascination with the mammals was ignited in the 1980s – like that of many children during that era – by watching Free Willy and CBC’s Danger Bay.

Shane Gero, Carleton University scientist-in-residence, has been researching sperm whales for over two decades (photo by the Dominica Sperm Whale Project)

This interest turned to passion, and eventually a career, when he began working with the legendary scientist, Hal Whitehead, at Dalhousie University during his PhD. Together, Whitehead and Gero journeyed to the Eastern Caribbean where they encountered families of sperm whales thriving off the leeward coast of Dominica. This finding launched Gero’s Dominica Sperm Whale Project (DSWP).

Since then, Gero and his team have put in thousands of hours observing the sperm whale population, detailing their behaviors and history. In 2019, Gero was approached with the idea for a large collaborative initiative – one that would attempt to understand whale communication whilst also focusing on conservation. Project CETI was launched a year later, where Gero is now the lead biologist. In 2021, Gero’s work with sperm whales contributed to an Emmy-award winning documentary, Secrets of Whales.

Decoding Whale Communication with AI

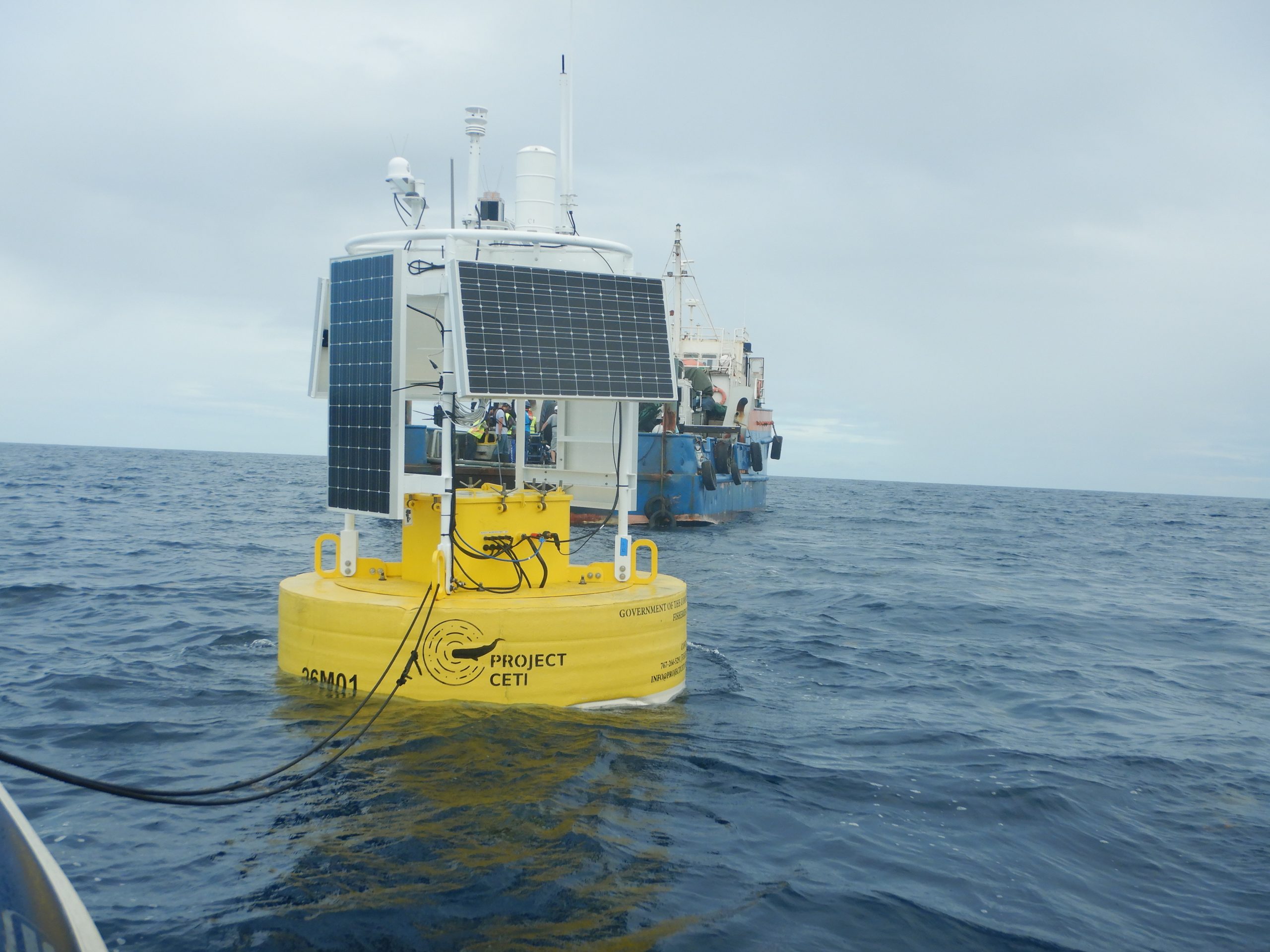

Project CETI is a non-profit organization made up of a team of scientists, technologists and conservationists. The group has deployed ‘listening stations’ off the coast of Dominica. Made up of dozens of underwater microphones, the stations record non-stop audio 365 days a year; localize where the whales are; and pinpoint which whales are making sounds.

Project CETI’s listening stations in Dominica record ocean activity all-year round (photo by Project CETI)

The team has also begun implementing artificial intelligence into their work. To better track the whales, they are developing autonomous drones that can fly over oceans, locate sperm whales, and place a non-invasive wearable device to their backs as they surface.

“These designs are not only advancing to the scope of marine biology, but they are helping us better contribute to conservation efforts,” Gero says.

The small computers, which stick on using suction cup technology, are programmed with sensors that allow the Project CETI team to monitor whale movement, heart rate, light, depth and much more. Given that these devices are non-invasive, they will eventually fall off – at which time the drones will be programmed to find and retrieve them.

Shane Gero placing a non-invasive listening device to capture whale communication (photo courtesy of Jennifer Modigliani)

Prior to this development, these animal-worn computers were larger and could only be deployed manually by researchers using a long pole to carefully place them on whales’ backs as they surfaced.

“We’ve mastered figuring out which whales are saying what, but the when, where and why is what we’re trying to decipher now,” says Gero. “That behavioral and social context is hard to capture on a bigger scale, but Project CETI is building the capacity to do just that.”

What Whales Have to Say

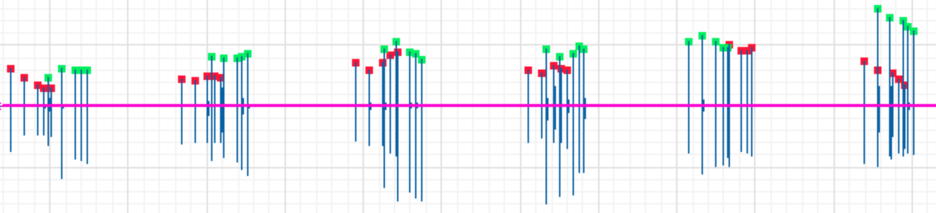

What Gero and Project CETI have discovered so far about whale communication is quite interesting. Sperm whales communicate through the use of codas, a series of clicks that are comparable to Morse code. Each clan’s codas are distinct, using different rhythms and tempos. This is how Gero is able to tell which whales they are listening to. The families that he’s been following use a specific coda which he calls the one-one-three to signify the pattern of their clicks.

“One thing that seems quite clear is sperm whales spend a lot of time saying, ‘I belong with these animals,'” Gero says.

“Their identity is important to them, where they come from, who they learned from, and how they live their life-because within a clan they do things differently.”

Sperm whales can dive over 1000m and can often hold their breath for over an hour , as such they spend around 10 minutes as surface to reoxygenate their blood (photo courtesy of Patrick Dykstra)

Just like humans from different backgrounds and cultures, sperm whale clans have diverse diets, and use different habitats, movement patterns, and behaviors.

“We can’t translate every click they make but it seems quite clear right now that a lot of their acoustic cues are announcing who they are, such as ‘I am Shane from family Gero and I am Canadian.'”

Lessons for Humanity

Sperm whales are the largest toothed whales in the world – reaching up to 18m in length with their head making up one third of their bodies. Yet, despite our inherent physical differences to these oceanic giants, Gero believes they have a lot to teach us about how to live our lives.

“One main take away from sperm whale life is that family is critical to survival,” Gero says. “Who you spend time with, whether their genetic family or not, makes for your life to be a success.”

Another lesson the whales have taught Gero is that humans need to overcome hardship by building a bigger definition of ourselves, not a smaller one.

Sperm whales are the largest toothed whales in the world – reaching up to 18 m in length and with heads that make up one third of their bodies (photo courtesy of Amanda Cotton)

“COVID and current global situations have made a lot of people very quick to discount someone as ‘them,’ or ‘other'” explains Gero. “In the oceans, it seems quite clear that building a more inclusive definition of ‘us’ and working together is how you succeed.”

Gero himself has been influenced by sperm whale’s commitment to family.

“They have changed the way I live my life,” Gero shares. “In 2016, we moved back to Ottawa because the kids’ grandparents are here – which is a very sperm whale thing to do.”

“I believe we can learn a lot from our neighbours (the whales) who are fundamentally different from us, yet seem to have figured out some things that are fundamentally important to us.”

Wednesday, October 25, 2023 in Biology, Environment and Sustainability, Faculty of Science

Share: Twitter, Facebook