By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

“If you thought getting to the truth was hard, getting to reconciliation is going to be really hard.”

So said Senator Murray Sinclair, the chair of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), in an address to a packed theatre in Carleton’s River Building on Oct. 3.

The evening event, presented by the university’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences and billed as an “inclusive discussion on Indigenousness in Canada,” was an opportunity for students, faculty, staff and other members of the Carleton community to learn more about the past, present and future of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from the man who has been at the heart of the process.

Sinclair, a Métis/Ojibwa from Manitoba who became the province’s first Indigenous judge, participated in hundreds of Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings across Canada and heard more than 12,000 testimonials and statements from residential school survivors and their families, “including some who only wanted to talk about the pain, not the future.”

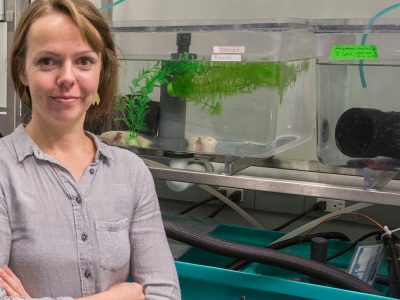

Senator Murray Sinclair, the chair of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission released 94 calls to action

He was front and centre when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its final report in December 2015, and he has remained a vocal advocate for the commission’s 94 calls to action since being appointed to the Senate in April 2016.

“We have a lot of work to do,” he said during his talk at Carleton, which last hosted Sinclair in November 2015 to present him with an honorary degree. “We’re not just talking about changing a system. We’re getting people to think differently.

“Residential schools were with us for 130 years, until 1996. Seven generations of children went to residential schools. It’s going to take generations to fix things.”

Education is one of the keys to reconciliation, said Sinclair, who likes the changes he has seen so far at elementary and high schools, where content on residential schools has already been added to some lessons.

Change can be difficult in a university setting, he acknowledged. But universities such as Carleton must remain on this path — and if you don’t persevere in the face of obstacles, he added, “then you will perpetuate.”

Responding to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission will be particularly difficult for the federal government, continued Sinclair, even though the prime minister “has said and probably intends to do the right thing.’’

“Government departments have to change the way they do business. Government needs to change its behaviour. We’re putting the responsibility to change in the hands of people who have made their careers by not changing.

“Change is not easy for most people, but for governments it’s really hard. They’re scared it’s going to cost them a lot of money, and if they spend too much they won’t get re-elected.”

Senator Murray Sinclair delivers an address to a packed theatre in Carleton’s River Building.

Children were punished for practicing their cultures in residential schools

Speaking without notes, Sinclair talked about the horrors of residential schools, where children were subjected to physical, sexual and emotional abuse; punished for speaking their languages or practicing their cultures; repeatedly told that Indigenous peoples were “inferior savages;” denied adequate food; and kept apart from their families, often for years, with parents not necessarily told when their child died.

“It was a genocide,” said Sinclair. “A policy of forced assimilation.”

The resulting legacy of intergenerational trauma is what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its calls to action seek to address.

“We need to grow toward a mutually respectful relationship,” said Sinclair, noting that one of the first steps is for Indigenous youth to regain a sense of self-respect and pride.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action begin with child welfare and education for this very reason, and then segue to language, culture and health. A stronger sense of identity, said Sinclair, will help Indigenous peoples find direction.

The event at the River Building began with a smudging ceremony on the patio overlooking the Rideau River.

Sinclair was introduced by Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller from Carleton’s recently renamed School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies — a change that received a loud burst of applause from the audience when it was mentioned by Horn-Miller.

“I would like to thank Senator Sinclair and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for the words and actions that inspired us to make this change,” she said, adding that Sinclair had donated his speaking fee to a bursary that will be given to a student in the Indigenous and Canadian Studies program.

Sinclair’s speech was also preceded by a few words from his wife, Katherine Morrisseau-Sinclair, who talked about what the TRC process was like for her and the couple’s children.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission Chair Sinclair’s speech was preceded by a few words from his wife Katherine Morrisseau-Sinclair (left). Also pictured: Interim FASS Dean Wallace Clement (right)

Morrisseau-Sinclair was concerned about Sinclair’s health and eating habits while he travelled and attended hearings. “Take him to the gym with you,” she’d say to his assistant. “Get him to walk more.”

At a Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearing she attended in Inuvik, NWT, Morrisseau-Sinclair described the testimony of a woman in her 90s who endured horrible beatings at a residential school. Afterwards, the woman’s children and grandchildren enveloped her with hugs.

“I knew it was important for him to do this,” Morrisseau-Sinclair realized. “The grannies needed him. The kids needed him. The moms and dads needed him.

“Everybody wanted him in their community. Everybody wanted him to hear their stories.”

The Carleton event had lighter moments too, such as Sinclair’s explanation of his nickname, The Justinator. Judges are allowed to keep the “Justice” honourific after they retire, and senators can always call themselves “senator,” so he has combined the two terms.

At one point during his talk, Sinclair’s cellphone rang. “That’s my elder,” he said while turning off the ringer. “He’ll have to wait.”

Wednesday, October 5, 2016 in Indigenous, Public Policy

Share: Twitter, Facebook