By Randy Boswell

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s threatened defamation suit against Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer over the SNC-Lavalin affair is just the latest in a rapidly growing list of Canadian political mud-slinging matches that have taken a litigious turn.

Scheer had already employed some overheated rhetoric at earlier stages of the controversy, accusing Trudeau of exerting “frankly illegal pressure” on former attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould over the prosecution of the Québec-based company on bribery and corruption charges.

But in late March, the Tory leader’s vague smears morphed into a more specific and unsubstantiated charge of criminality, the most severe kind of malfeasance in the political arena.

A statement by Scheer — circulated via Twitter and Facebook, beyond the robust legal protections afforded by Parliamentary privilege — said Trudeau’s actions in the affair amounted to “corruption on top of corruption.”

A letter from Trudeau’s lawyer highlighted the “corruption” claim against the prime minister as particularly egregious because it painted him as the perpetrator of “the worst political conduct possible, being corruption, which is deserving of a criminal penalty of up to 14 years’ incarceration.”

Following the playbook

In serving that notice of libel, Trudeau was following the playbook of modern Canadian political leaders. In fact, each of the country’s three previous prime ministers got lawyers involved when their main political rivals stepped over the rhetorical line between vigorous debate and alleged slander.

In March 1998, then-prime minister Jean Chrétien threatened to sue Preston Manning and other Reform MPs if they repeated — outside of the House of Commons — an accusation that newly appointed B.C. Senator Ross Fitzpatrick was the beneficiary of a Senate “seat sale” after Chrétien had benefited financially years earlier from a Fitzpatrick stock tip. Manning moderated his attacks and the threatened lawsuit never materialized.

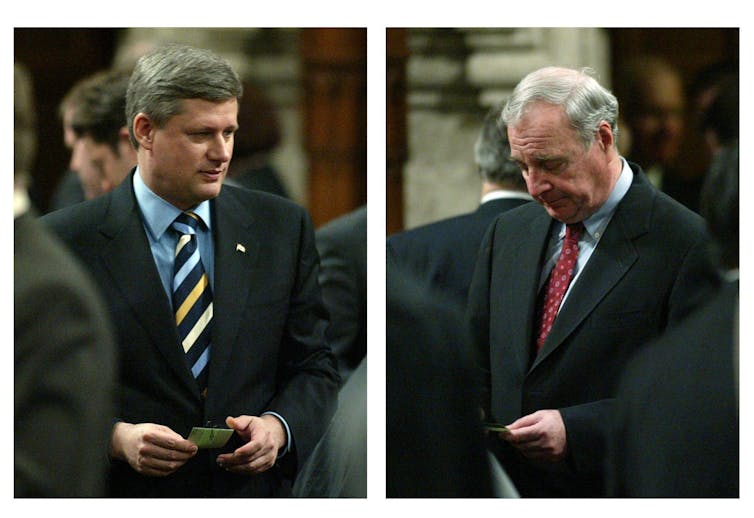

In November 2005, former Liberal PM Paul Martin’s legal team issued a libel warning to Stephen Harper after the then-opposition leader (under the protection of Parliament) accused Martin of heading a party that broke “every conceivable law in the province of Québec with the help of organized crime.”

Laws were broken and perpetrators were eventually jailed in the post-1995 referendum sponsorship scandal, but there was never any evidence that organized crime was involved.

Forgotten threats

In media statements and a shot-across-the-bow lawyer’s letter to Harper demanding an apology, the Liberals warned the Conservative leader that if he uttered the same “false smear” outside the Commons, he’d be facing a defamation suit. But a few months later, with no apology offered and the threatened lawsuit seemingly forgotten, Harper was elected prime minister.

While Conservatives had dismissed Martin’s lawsuit threat as pure bluster and an attempt to gag critics, Harper as PM took the same legal route in March 2008 after then-Liberal leader Stéphane Dion accused the prime minister of knowing about an alleged 2005 “Conservative bribery” attempt to manipulate independent MP Chuck Cadman, dying of cancer at the time, in a crucial House of Commons vote.

There was no proof that Harper knew about the nature of the dealings with Cadman. He said the suit was necessary to safeguard his honour: “I have every right, as does my family, to defend our reputation.”

Suit against Harper fizzled

To Dion, Harper was wielding the defamation threat to “bully” his Liberal opponents into silence on the matter. The lawsuit fizzled and was dismissed without costs in 2009.

Trudeau — like Martin in 2005 and Harper in 2008 — was just months away from a federal election when he threatened his chief opponent with court action.

It’s no wonder critics see such libel notices as primarily aimed at slapping a lid on damaging accusations at a time when voters are about to pass judgment on a government. But it’s no surprise, either, that opposition rhetoric gets amped up to legally risky levels when all parties are girding for an election.

Accusations of defamation have become almost routine in Canadian politics in recent years.

Former Ontario premier Kathleen Wynne, for example, filed lawsuits against successive provincial Progressive Conservative leaders Tim Hudak and Patrick Brown over their inflammatory attacks, respectively, that she “oversaw and possibly ordered the criminal destruction of documents” (no such evidence) and was “on trial” in a case of alleged bribery (she was, in fact, called to court as a witness).

Extracted apology

The Hudak suit was settled or withdrawn in 2015; the Brown suit appears to have been dropped. In September 2017, Wynne did extract an immediate apology from Conservative MPP Bill Walker after threatening to sue him for falsely saying she was under investigation for bribery.

Brown, in turn, was recently sued by his ex-ally — Ontario Finance Minister Vic Fedeli — over statements in Brown’s new book alleging scurrilous behaviour by Fedeli before and during the 2018 upheaval among Ontario Tories that put Doug Ford on the path to becoming premier (and Brown en route to the mayoralty of Brampton.)

University of Guelph political scientist Byron Sheldrick argued last year in a Maclean’s article that the sharp rise in politically motivated defamation battles could lead to the stifling of constructive political debate in Canada. He has urged a SLAPP-type testing of defamation claims in the political arena to weed out strategic lawsuits launched to smother harsh criticism from those cases in which genuine reputational harm seems to have been inflicted by a partisan rival’s reckless words.

Not a new idea

If the idea gains traction, the recent upward trend in political defamation claims could be curbed. But it’s unlikely to end a phenomenon as old as Canadian politics itself.

In 1878, during Sir John A. Macdonald’s years in the opposition wilderness, the notoriously heavy drinker was spotted passed out in the House of Commons and being discreetly carried to an antechamber by fellow Tories. Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie described the scene in a note to fellow Liberal titan George Brown — a Grit senator, publisher of the staunchly partisan Globe newspaper and for decades Macdonald’s arch nemesis — who printed an editorial condemning Sir John A.’s behaviour.

“To say that Sir John Macdonald was on Friday night somewhat under the influence of liquor would be a grossly inadequate representation of fact,” the Globe stated. “He was simply drunk in the plain ordinary sense of the word.”

The accusation was widely republished in the Liberal press, and a flurry of threatened lawsuits from Macdonald followed, none of which was acted upon — perhaps because truth is an absolute defence against a charge of libel.

Nevertheless, Macdonald reclaimed the prime ministership in the 1878 election and — occasional bouts of drunkenness and defamation notwithstanding — kept it until his death in 1891.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Monday, April 22, 2019 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook