By Jena Lynde-Smith

Photos by Cindy Yifan Hu & Terence Ho

Imagine being surrounded by a symphony of sound, each instrument harmonizing to create a rich tapestry of music. The conductor stands at the podium, baton in hand, guiding the ensemble. Musicians, deeply focused, respond to these cues, their eyes darting between sheet music and the conductor. For most, this is the essence of playing in an orchestra — a seamless blend of visual and auditory stimuli.

However, for blind and low vision musicians, this experience is vastly different. Traditional methods of synchronization like following a conductor’s baton, reading sheet music or observing non-verbal cues, are not accessible. This lack of visual input creates a significant barrier, preventing full participation in not only musical ensembles and performances, but music learning in general.

Leon Lu

Leon Lu, a Information Technology PhD student at Carleton University, is transforming this reality through the development of wearable haptic devices. Coined the tap-tap project, these devices assist blind and low vision musicians by enabling teachers and music learners to send vibration signals in real-time to one another, replacing the need for visual cues.

“We often think about accessibility in terms of basic human needs like getting from point A to point B or accessing information. But what about having access to the things that make life more enjoyable and meaningful?’” says Lu.

“Music and creativity, some may argue, are not necessarily things that everyone needs to have access to. But in my mind, they are extremely important aspects of the human experience.”

Beyond Traditional Accessibility

Lu developed the tap-tap device as part of his PhD dissertation. The idea came from conversations he had with blind and low vision musicians. In these initial discussions, he discovered that non-verbal communication was a major hurdle. When trying to follow a teacher or conductor, subtle head nods or hand gestures can’t be observed, making it difficult to follow instruction and keep time.

One story stuck out to Lu. He was told that when playing in a group, blind and low vision musicians sometimes ask fellow musicians to tap on their shoulder as a cue to start playing.

“This got me thinking – there must be a technological intervention here that could do this ‘tapping,’ for them,” reflects Lu. “And so, I set to work on the tap-tap project.”

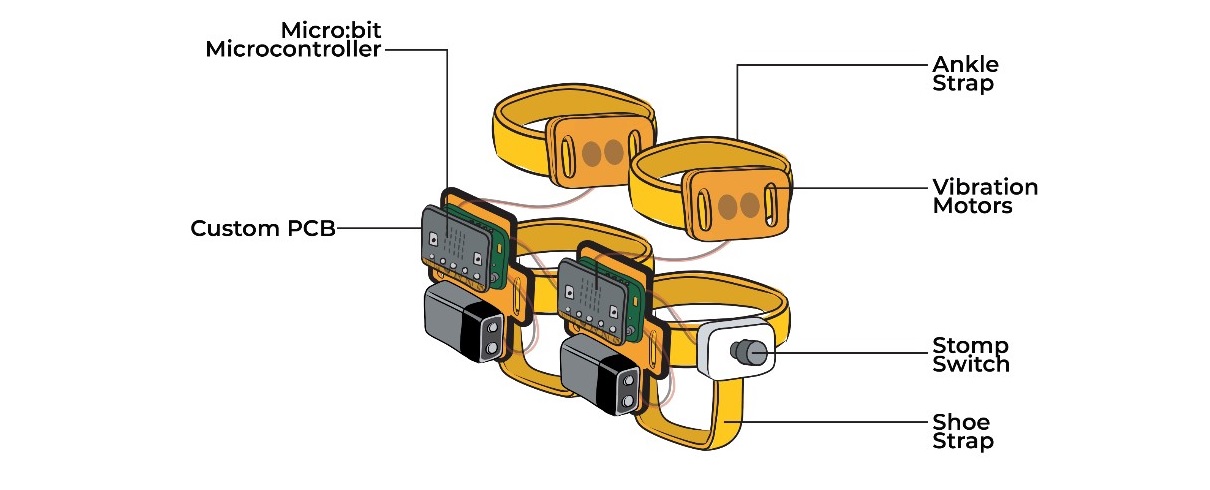

The tap-tap is worn around the ankles of music learners and teachers, allowing them to communicate with one another by simply tapping their heels together to push a button. When pressed, the button sends a vibration to the paired device. These vibrations can be used to create codes as a way to communicate messages non-verbally.

“Similar to Morse code, the tap-tap’s vibrations replace visual cues with tactile ones,” says Lu.

The nuts and bolts of the tap-tap devices are simple. Each one has a small circuit board with sensors and a radio component – which is how Lu programs them to communicate. A small motor is what prompts the vibration and other than, it’s mostly just straps and Velcro.

“The device itself is very low cost,” Lu says.

Improving Learning for Blind and Low Vision Musicians

Lu developed the tap-tap devices with the help of two fellow Carleton students: Aino Eze-Anyanwu, an undergraduate student in industrial design, and Rodolfo Cossovich, an information technology PhD candidate. He also worked in consultation with Chase Crispin, a blind musician and teacher in Lincoln, Nebraska.

“Getting involved with Leon’s study was a way to blend my own interest in technology with the needs I had as a blind musician,” explains Crispin.

“Many people don’t realize how much a musician is managing at once: posture, notes, rhythms, dynamics—the list goes on. For blind music learners, who memorize most of this, it adds even more layers.”

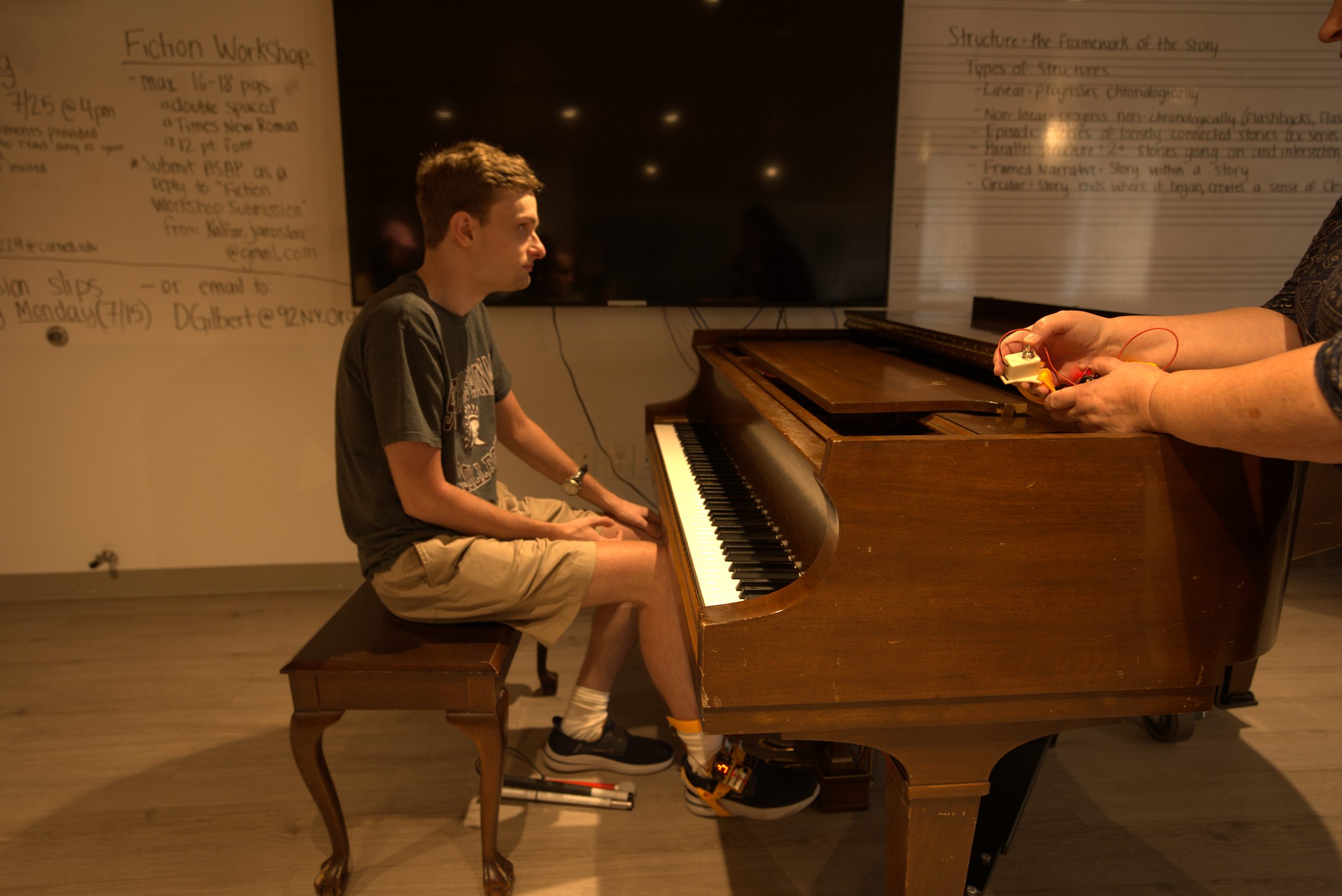

After completing the prototypes, he invited teachers and students from the Filomen M. D’Agostino Greenberg (FMDG) Music School – a music school in New York City for blind and low visions musicians – to try them out. Over the course of eight weeks, the devices were implemented into violin, piano and singing lessons.

Nora Bartosik, a piano teacher at the FMDG Music School, integrated the device into her weekly sessions, using it to send real-time coded messages to signal actions. For instance, a long vibration signaled an increase in volume, while two short vibrations indicated a decrease.

“The tap-tap device offered my students an entirely new and different way of absorbing information during their musical lessons,” Bartosik says. “We discovered ways of communicating musical directions that we would never have thought about without trying the device.”

Sami Osborne, a student of Bartosik’s, found the tap-tap to be particularly helpful as it reduced the number of times his teacher would have to stop and interrupt playing to explain something.

“Using the tap-tap was fun and interesting,” he says. “My piano teacher and I experimented with different vibration patterns to adjust tempo and dynamics during lessons.”

“It’s a great way to facilitate nonverbal communication during music lessons, especially when either the teacher or student is blind.”

The Future of the Tap-Tap

Stationed back home in Toronto, Lu is now analyzing the data and feedback gathered from his study with the FMDG Music School to refine the device and finish his thesis, which is being supervised by Carleton Prof. Audrey Girouard.

After graduating, Lu hopes to make the device open-source.

“I don’t want there to be a cost attached,” he says. “If people want it and if they find it useful, I want them to be able to use it – I’m happy to help with that.”

In addition to music learning, Lu says the device could be customized to fit other uses.

Notably, he is working with Caroline Pakėnaitė to potentially upgrade the device to help her summit Mount Everest. Pakėnaitė has Usher’s Syndrome, which degenerates both sight and hearing over time. Lu hopes the tap-tap will help her communicate with her climbing partner.

“This device has a high-floor, low-ceiling,” he says. “While it’s very simple to understand, the potential uses are countless.”

Tuesday, July 30, 2024 in Accessibility, Faculty of Engineering and Design, Music

Share: Twitter, Facebook