When asked to imagine someone who abuses drugs or alcohol—someone with a substance use disorder—most people picture an older, possibly homeless man who’s somehow disconnected from society.

“You’ll think of all sorts of negative images,” said clinical health psychologist Kim Corace at the Psychology Let’s Talk Lecture. “[But] people who use substances are everywhere. They are people in risky housing situations and people with two-car garages.”

The wide range of substance use disorders is varied in Canada and they are so common that every Canadian is likely affected.

Kim Corace

A 2018 study conducted by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research estimated that substance use in Canada costs an overall $38.4 billion, or approximately $1,100 for every Canadian. These costs range from lost productivity, healthcare costs and criminal justice costs, among others.

Alcohol and tobacco contribute to two thirds of this cost, while opioids and cannabis contributed about 16 per cent of total costs.

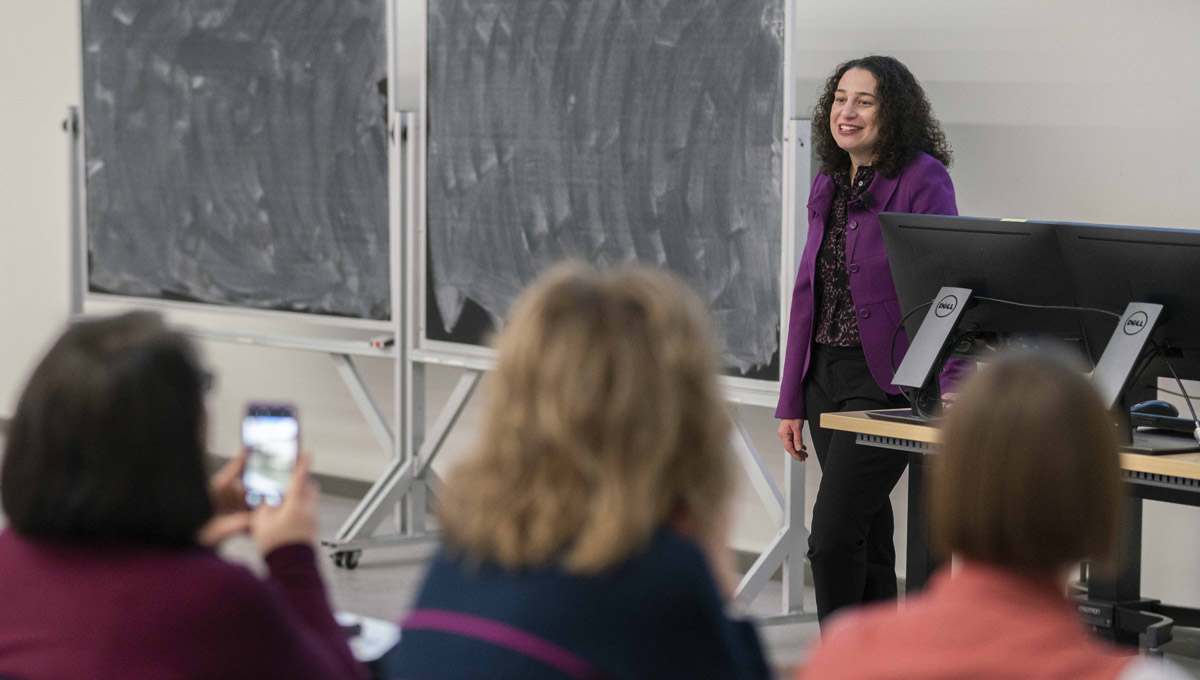

Corace, the director of clinical programming and research in the Substance Use and Concurrent Disorders Program (SUCD) at The Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, described the current drug crisis and the Canadian healthcare challenges to a packed lecture hall in the Health Sciences Building on Jan. 30, 2020.

She was the inaugural lecturer of the lecture series created by Carleton’s Department of Psychology and built off of Bell Let’s Talk Day, an annual awareness campaign to break the stigma around, and raise funds for, mental illness.

She detailed several of the barriers that exist to health services for people with complicated health challenges.

“We have a system of silos where the mental health system and the substance use system don’t work together,” said Corace. “The silo system is harming and literally killing people.”

People seeking substance-use services are often turned away when clinicians recommend they improve their mental health first. Alternately, people seeking help for their mental illnesses are told they need to stop using drugs or alcohol first.

“People are ping-ponging between places because they don’t fit anywhere, and then they end up nowhere,” said Corace.

Corace graduated from Carleton’s Department of Psychology in 1994 and received her PhD in Clinical Psychology at York University in 2008. She is an associate professor at the University of Ottawa as well as an adjunct research professor at Carleton University.

Corace’s role at The Royal puts her at the forefront of innovative care models that aim to reduce barriers and to retain patients. The SUCD is offering one such integrated method known as the Rapid Access Addiction Medicine (RAAM) Clinic.

The walk-in clinic is for anyone concerned about their substance use who might also have mental or physical health issues. Each individual is assessed and recommended an appropriate level of care that links to community resources.

The majority of 466 patients who frequented the RAAM clinic between June 2016 and March 2019 expressed satisfaction with the program. It was designed to provide treatment quickly while not adding any extra costs to the healthcare system.

Young people with substance use disorders have their own barriers to treatment. They are often concerned about their confidentiality and about clinician attitudes toward them, and they require specialized services, said Corace.

There is currently not enough research into the effectiveness of treatment programs for youth who use opioids. Finding out more is particularly urgent to help treat Canadians between the ages of 15 to 24 because this group has the fastest-growing rate of hospitalizations due to opioid poisoning over the last decade. In 2018 alone, this age group saw 140 opioid-related deaths, almost 1,400 emergency department visits, and 216 hospitalizations in Ontario alone.

One of The Royal’s innovative programs is for patients between 16 and 29. The Regional Opioid Intervention Services (ROIS) offers outpatient opioid agonist therapy and follow-up services, as well as mental health and substance use treatment based on each client’s unique needs.

Barriers come in all sizes and stigma is one of the largest. Too often, people in need of medical assistance are judged and rejected because of their ethnicity, language, sexual orientation or age. Corace noted how sometimes a disability or a history of trauma can prevent people from being helped.

“Think about it,” she said. “These people are considered too sick to be helped.”

Corace addressed Psychology students directly when she called for massive efforts of collaboration and research. She challenged the next generation of psychologists and clinicians to help develop the list of patient outcomes that should be studied in the future.

Patients want to function better, go to school again, be fairer to their partners and get along with their friends, but currently these outcomes aren’t studied nearly enough, noted Corace.

To determine what’s important and what works will mean engaging the people who are most affected. Clinicians, researchers and policymakers have a part to play, but people with lived (and living) experience, and their families and friends, will help drive meaningful research.

“As psychologists we have a very unique responsibility to raise awareness and reduce stigma around mental health,” said Carleton Psychology Prof. Robert Coplan as he introduced Corace. “Despite continuing improvements, there still remains a sizable proportion of children and adults who do not, or are not able to, access potentially life changing treatments and services.

“This is why we should all aspire to be more like Dr. Corace.”

Tuesday, February 4, 2020 in Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Psychology

Share: Twitter, Facebook