Lead image by Apisorn / iStock

By Dan Rubinstein

Twenty years ago, Laura Hall saw a movie and had an epiphany.

The longtime fan of horror films sat down to watch The Descent, a 2005 British production in which a group of women explore a spooky cave system. Cue the monsters and mayhem.

“A woman falls into a deep pool of thick blood and emerges only to be attacked by a cannibalistic humanoid in the depths of caves in Cherokee homelands,” Hall, now a sociology and anthropology professor at Carleton University, writes in the opening of her brand-new book Bloodied Bodies, Bloody Landscapes: Settler Colonialism in Horror.

Carleton University sociology and anthropology professor Laura Hall

“They aren’t really still making movies depicting Indigenous people as cannibals,” she thought at the time.

“No way! They are! This isn’t just a ‘past problem.'”

Hall’s realization — that even in the 21st century, horror films rely on racist Indigenous stereotypes to scare audiences — sent her in a new research direction. And while she remains an aficionado of the genre, watching Halloween every Halloween and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at least once a year (when her kids are asleep and her partner is out), as her book reveals, there’s a lot to unpack from a critical academic perspective.

“Many horror movie narratives are about conflict between civilization and savagery,” says Hall, “and many of the demons that attack people are racialized ‘primitives’ with not-too-subtle elements of indigeneity.”

A Love for Horror and Halloween

Growing up in Sudbury, Ont., Hall developed a love for scary stories and over-the-top Halloween decorations from her father, who was born in England and worked as an engineer in the mining industry. (“I became a diehard environmental and Indigenous rights activist, of course, living in a mining community,” she quips.)

In the 1980s, horror films were mainstream. By age 12, she was renting moves like Friday the 13th on videotape with her friends.

Hall’s upbringing was also shaped by her mother’s Mohawk side of the family, who were from Kahnawake, Que. She fished, picked blueberries and was encouraged by her mother to learn about Mohawk history and culture.

But even though she was exposed to Indigenous tropes in the moves she watched — the zombie animals in Pet Sematary and haunted house in Poltergeist, for example, are both spawned by ancient “Indian” burial grounds — Hall’s research and cinematic interests didn’t intersect until she saw The Descent.

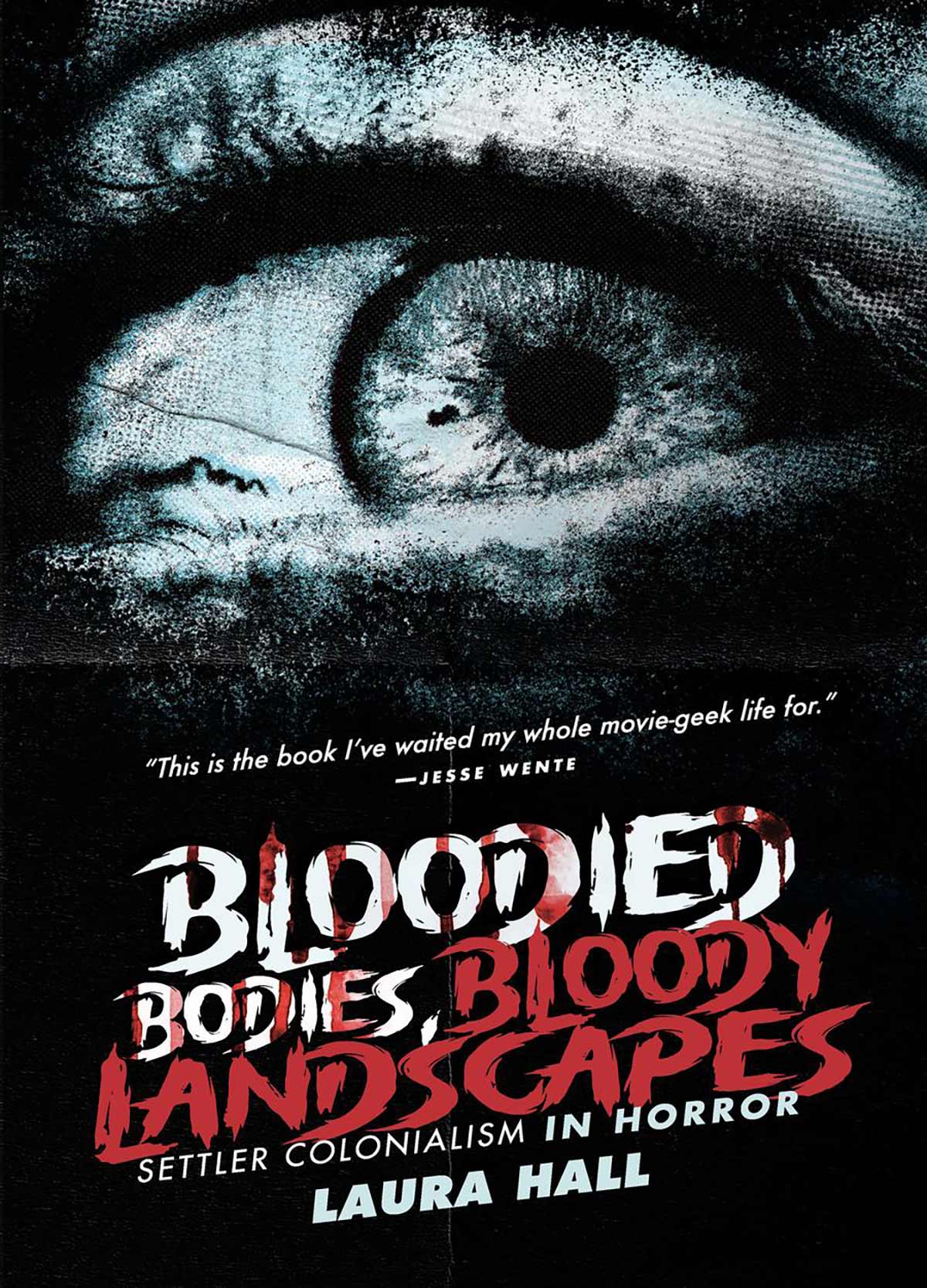

Promotional poster for The Descent (Neil Marshall, UK, 2005). Celador Films / Pathé / Lionsgate

After an undergraduate degree in Canadian Studies at Carleton, Hall went to grad school in Toronto, where she scoured reference libraries for academic analyses of horror films and rented “weird movies” from Suspect Video.

Now, nearly two decades later, she makes some eye-opening observations in Bloodied Bodies, Bloody Landscapes, among them the idea that the violence inflicted upon Indigenous Peoples by colonizers is often inverted in film.

“It is this appropriation of Indigenous suffering that makes horror so crucial to settler colonial storytelling,” she writes.

“Horror may seem to disrupt settler worlds, but it appropriates the suffering and bloody violence of colonization…

“The idea then becomes that fantasies of this kind of suffering and fear can be projected onto the screen for white settlers to consume. Indigenous Peoples have seen genocide and ecocide, only to birth new generations in a world overtaken by colonizers who both appropriate and disappear those stories, all while making this twisted notion of the savage, the Indian, into the real monster. Alongside appropriations of suffering, there are those fears that the colonized will seek revenge.”

Horror Stories Reinforcing Indigenous Stereotypes

Amid the drawn-out response to the calls to action from Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, Hall argues that efforts to seek equity and justice can be undercut by fiction.

“Many of these movies portray Indigenous women as monsters,” she says.

“In this realm of storytelling, this notion of savagery is continuously reinforced.”

How can the average Canadian respond with empathy, she asks, when they’re being taught to fear?

This doesn’t mean Hall wants horror films to be censored. She’s an advocate for critical thinking, so people understanding what they’re watching.

Promotional poster for Slash/Back (Nyla Innuksuk, Canada, 2022). Mixtape VR / Good Question Media / Scythia Films / Stellar Citizens.

“It makes horror even more interesting if you’re analytical,” she says.

“We should be able to have conversations about ‘Indian’ burial grounds and the real depths of these issues.”

Hall also calls for space for more Indigenous-made horror movies, a burgeoning genre that includes 2022’s Slash/Back, director by Inuit filmmaker Nyla Innuksuk, in which a group of girls work together to fight an alien invasion in Nunavut (which Hall calls a “pretty good metaphor for colonization”).

“The original horror of the North American continent unfolded in 1492, with the onset of mass European arrival, invasion, and genocide,” she writes in the conclusion of Bloodied Bodies, Bloody Landscapes. “Decolonization necessitates material as well as ideological renewal and return for Indigenous Peoples. Telling better stories is also about providing the material basis for Indigenous people to tell those stories ourselves.”

Bloodied Bodies, Bloody Landscapes: Settler Colonialism in Horror by Laura Hall

First wide image by Randomerophotos / iStock

Second wide image by Maya23K / iStock

Friday, October 17, 2025 in Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook