By Laura Byrne Paquet

In 17 ambiguous words, Section 35.1 of the Constitution Act, 1982 set Canada on a new path that is still unfolding.

The section reads: “The existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

“We possess that inherent right to self-government; we possess that right because it was bestowed upon us by our Creator, by natural laws [and] we’ve never voluntarily given up that right,” says Edmund Bellegarde, Tribal Chief and CEO at File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council Inc. in Fort Qu’Appelle, Sask.

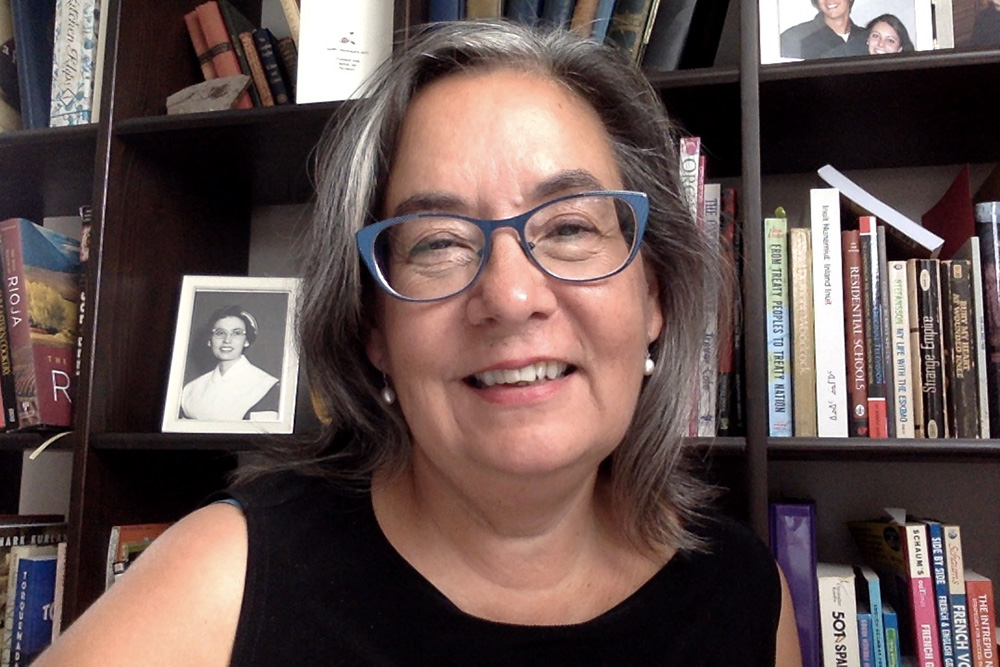

Chancellor’s Professor of Public Policy and Administration Frances Abele

Bellegarde is among many Indigenous chiefs, academics, practitioners and community members working with Carleton University’s Frances Abele on the Rebuilding First Nations Governance (RFNG) project addressing wide-ranging questions about what self-government looks like and the constraints of the Indian Act.

The grassroots initiative is supported by a $2.5-million grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and is affiliated with the Carleton Centre for Community Innovation (3ci). Over the next six years, the project will work with Indigenous communities to research issues they have selected as important to achieving their self-governance goals.

The roots of the RFNG project go back many years. One inspiration was a court case, Delgamuukw v British Columbia, in which the Supreme Court of Canada provided a legal definition of Aboriginal title and of the way it can be proven—definitions that have played a role in subsequent court cases.

Connecting with Carleton

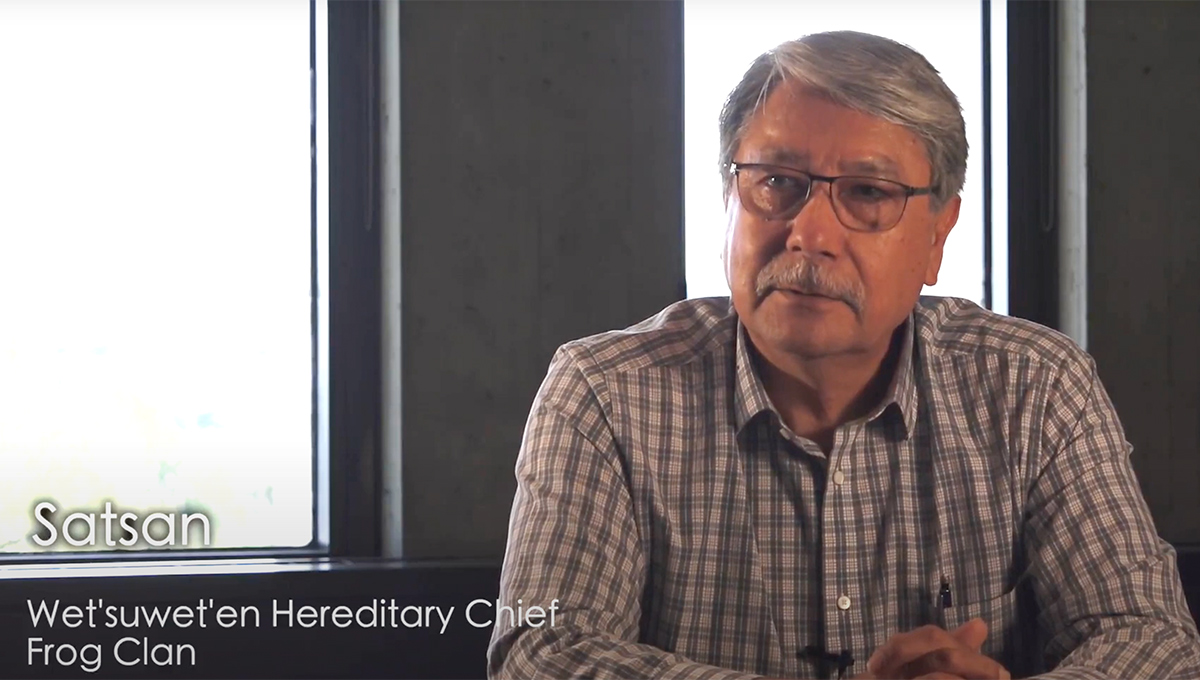

Satsan (Herb George), one of the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs of the Frog Clan of British Columbia, was deeply involved in the Delgamuukw case. Later, he founded the Centre for First Nations Governance.

Project Co-Director and Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Satsan (Herb George)

In 2012, Satsan approached Abele, Chancellor’s Professor of Public Policy and Administration at Carleton, to discuss a national research network led by Indigenous communities. They became the project’s co-directors, joined by project manager Catherine MacQuarrie, a former federal public service executive who is Métis and has extensive policy experience in Indigenous issues.

Together, they organized a series of preliminary meetings and think tanks. A webinar series in 2021 is investigating various aspects of self-government, with the next event on April, 28.

Despite challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the project has already forged partnerships with six First Nations and two Tribal Councils, six Canadian universities, three non-governmental organizations and 35 academic researchers and practitioners.

Project Manager Catherine MacQuarrie

Notably, says Abele, Indigenous partners will drive the project’s work. After determining their local priorities and the types of information they need, they will work with academic partners to carry out the necessary research.

“The project is First Nations led,” she points out.

“It is a true partnership.”

Four Regional Clusters

To better reflect regional legislative frameworks and concerns, the project has been divided into four regional clusters, each with two co-leads.

The West Coast Aboriginal Title Lands cluster focuses on British Columbia. Cluster co-lead Terry Poucette, a faculty member at Carleton and the University of Victoria, explains that Indigenous peoples in B.C. have a unique position because Canada never signed treaties with them.

“The lack of treaties means that the B.C. First Nations are still the rightful owners of their territories. This land was never ceded,” explains Poucette, who is from the Stoney-Nakoda First Nations of Treaty Seven in Alberta.

“It really puts them in a position of power.”

On the East Coast, the Peace and Friendship Treaties cluster is dealing with a different legislative framework. At the moment, that cluster is focusing on the pressing issue of fisheries control and regulations, where the networking advantages of the RFNG project are already starting to emerge. The project has helped Nova Scotia researchers connect with the Nipissing First Nation in Ontario, which has already created its own fisheries laws.

When the RFNG project ends, a website packed with videos, research and case studies will remain to foster knowledge mobilization across the country.

“That’s meant to be the legacy of the project,” says Abele.

Mentoring the Next Generation of Academics

Another key goal of the project is to encourage, support and mentor the next generation of Indigenous academics. “We hope to grow the numbers of students who are actually interested in working in this field,” says MacQuarrie. “The vast majority of academics we have working with us are Indigenous . . . For potential students to be able to see those examples in such a large number—I think that will help.”

As part of that effort, the project hires graduate and postdoctoral students like Amsey Maracle. A Carleton Master of Public Policy student who is Mohawk and Plains Cree, Maracle joined the RFNG project as a research assistant in March 2020. She says the job has been inspiring.

“I’m in awe every day of the mentorship opportunities [and] the people who I’ve been able to engage with because of this project,” she says.

“It’s unreal, and it’s so exciting.”

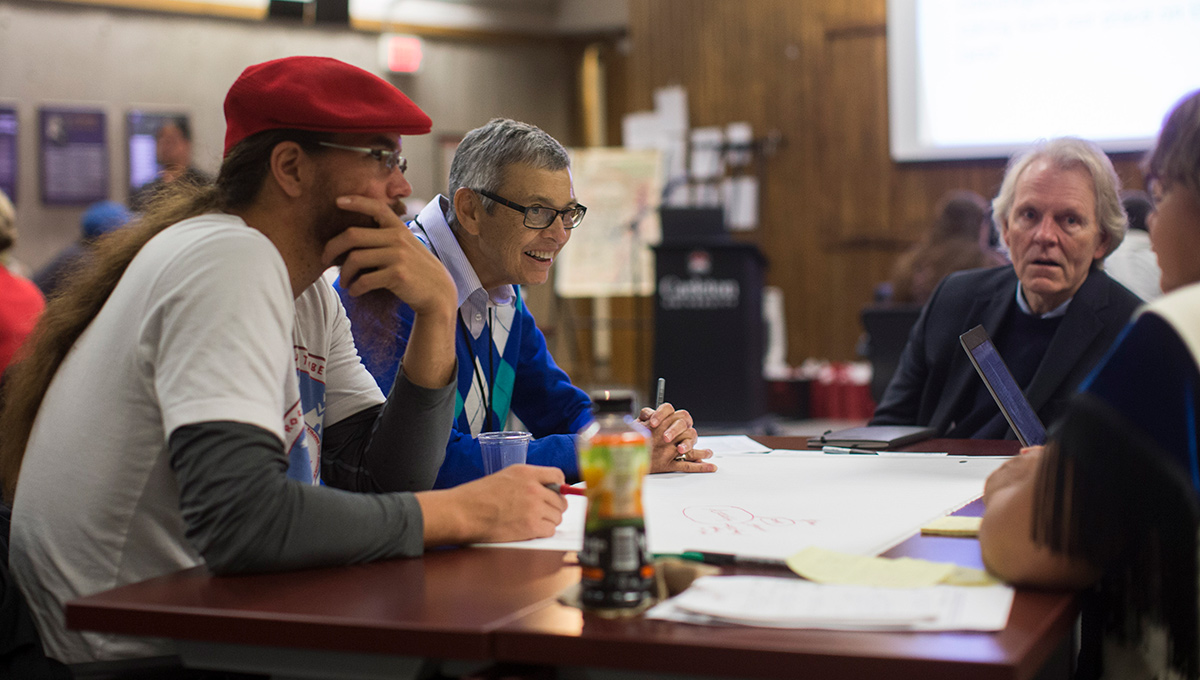

Roundtable discussions at the 2017 Transitional Governance Conference

Many of those involved note the project’s success will hinge on developing a deep understanding of the myriad ways the Indian Act affects every aspect of Indigenous life in Canada—and then helping people escape from its long shadow. Poucette notes that despite their hatred for the act, many Indigenous people are reluctant to cast it aside because they don’t know what might replace it.

“[Many believe that] staying under the Indian Act will ensure that government upholds its fiduciary responsibilities to First Nations. So it’s very difficult to move from the Indian Act,” she says. “This research is going to allow us to speak directly to communities about those fears and about the things that are keeping us stuck, and [look] for ways to alleviate that fear and move towards implementing our inherent right.”

Satsan agrees that changing mindsets and empowering people is key.

“This nation-rebuilding project is about reorganizing our people to kind of decolonize their minds and their consciousness, to get rid of that anger and the pain that’s associated with it. So that we can talk about the kind of future that we want to have for our children and future generations. And so that we can fulfill our responsibilities and obligations to our lands, and the resources and all the living beings there.”

Once communities understand that self-governance can happen and can improve their lives, it will be easier for people to support the concept and to make it real, he adds.

“Hope is big medicine,” he says. “The big challenge is getting our people to that place. Once they’ve accomplished that, then to me, it’s inevitable. They’re going to get it done.”

Monday, March 29, 2021 in Indigenous, Partnerships

Share: Twitter, Facebook