By Hannah Dick

One day after the surprise victory of the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) in the recent Québec election, Premier-elect François Legault told a news conference that he plans to invoke the notwithstanding clause to finally pass legislation that will ban religious symbols for employees in “positions of authority” throughout the province.

But even though the Québec election is being described as a landmark shift in political power, the threat to ban religious symbols throughout the province’s public service sector is nothing new.

Politicians in the province have been trying to pass various religious symbols bans for the past decade, including the Parti Québecois’s sweeping Values Charter from 2013 outlawing “conspicuous” religious symbols for anyone giving or receiving public services.

Under the leadership of Philippe Couillard, the Liberals passed more modest legislation: Bill 62, which singled out full-face coverings in the public service sector, was passed in October 2017. But the law was quickly stayed by a provincial judge.

Challenged by civil liberty groups

Each of these attempts has been challenged by groups like the National Council of Canadian Muslims, the Canadian Council of Muslim Women and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

These organizations point out that much of the proposed legislation has singled out a small number of Muslim women who choose to wear the full-face covering niqab rather than applying broadly to all religious symbols.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms has played a key role in preventing the widespread adoption of these laws, which appear only to circumscribe the religious symbols of minority groups.

Indeed, since the 2013 Values Charter, legislation banning religious symbols has included exemptions for “the emblematic and toponymic elements of Québec’s cultural heritage, in particular its religious cultural heritage, that testify to its history.”

This clause effectively exempts Catholics from the secularization mandate by redefining their religious symbols as “cultural” and “historical” rather than religious (and, notably, creates an exception for the large crucifix that hangs at the head of the National Assembly). It is yet unclear whether the CAQ’s attempt will include a similar exemption.

Minority government

PQ Premier Pauline Marois also made threats about her party invoking the notwithstanding clause to pass the Values Charter in 2013.

But the PQ had a minority government at the time, and Marois unsuccessfully risked an election to get a broader vote of confidence.

Legault’s comments, in comparison, come on the heels of Premier Doug Ford’s threat to use the notwithstanding clause for the first time in Ontario, suggesting that the Charter has become something of a pawn in the struggle between right-of-centre provincial populists and the federal Liberals.

That Legault’s comments also come before he enters the premier’s office — and backed by a majority government — signals that his attempt to pass a “secularization” bill might be successful.

If that’s the case, the CAQ’s success where other parties have failed will come at the cost of both civil rights in the province and the protective capacity of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

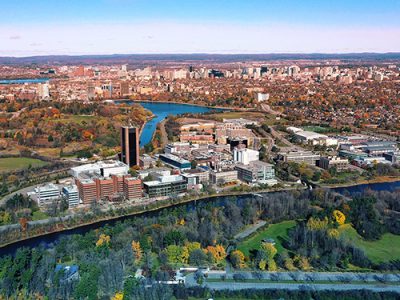

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Thursday, October 4, 2018 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook