By IndieWire

Aboubakar Sanogo is a scholar of African cinema and works for the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), but it took him years to see one of the major films from the continent: Med Hondo’s Soleil O, a 1969 portrait of a black immigrant in Paris, was long revered but widely unavailable. Sanogo didn’t see it until a print surfaced in Paris in 2006.

“Even in Burkina, the capital city of African cinema, it wasn’t available,” Sanogo said in New York in early June. “It’s a huge problem.”

Sanogo was addressing a broader challenge facing the preservation of African film history — and one that might be facing a brighter future.

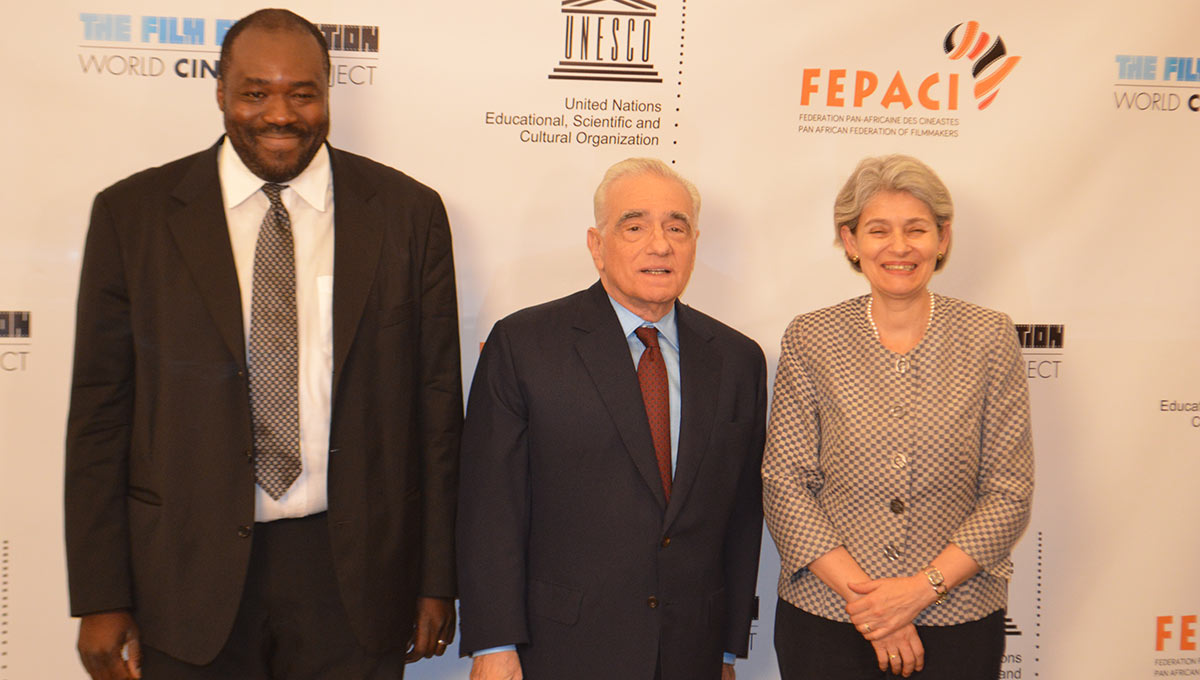

Left to right: African cinema scholar, Prof. Aboubakar Sanogo, celebrated film director Martin Scorsese, and UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova. Photo courtesy of Dave Allocca/Starpix Courtesy of The Film Foundation.

On June 7, FEPACI, UNESCO and Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation World Cinema Project signed a letter of agreement formalizing their partnership on the African Film Heritage Project, a joint initiative to preserve African cinema. But their work has already shown major results, with Soleil O screening in the Cannes Classics section last month.

The project “will restore, disseminate … in Africa and around the world, a collection of the films from Africa that are historically, artistically and culturally significant,” Scorsese said at the event in New York.

Later, he explained how his interest in African cinema grew out of his passion for Souleymane Cissé’s 1987 sorcerer drama Yeelen, which he saw on television. Eventually, he formed a relationship with Cissé and visited him in Mali.

He was struck by a comment that Cissé made when they were both in Cannes for a different partnership in 2007.

“He said: ‘If we don’t try and restore African cinema — made by Africans about Africans — then future generations will never know who they are,” Scorsese said.

“Cinema is a perfect way to open up the mind, curiosity for other cultures.” (For more on Scorsese’s efforts to support the international film community, go here.)

Broadening Awareness

for African Cinema

For Sanogo, the new initiative opens up an opportunity to broaden awareness for African film history that has been marginalized for decades. With historical context, the older films can enjoy a new life in the classroom and repertory cinemas around the world.

“In many ways, the auteurist tradition in Africa is an experimental cinema,” he said.

“That is part of its problem — experimental cinema and audience appreciation don’t always go hand in hand. So we are trying to bring these images back, not only to filmmakers but Africans in general.”

He underscored a developing concern for educating film students in Africa about their heritage at a time in which film production has increased. “Filmmakers are making films in Africa every day,” Sanogo said. “The advent of digital has made the medium more accessible.

“I took my students to Burkina in 2012 to study Burkina cinema. They dreamed to one day hold a piece of celluloid film and shoot on it. In film school, they simply didn’t have celluloid to shoot on. But the energy and desire to make films has never been as high in Africa as it is today.”

UNESCO director-general Irina Bokova also attended the signing and added a broader context to the discussion.

“Cinema is about history and storytelling,” she said. “African films are a [form of] cultural expression. It’s also about trying to change the narrative of this history, so it’s not from the point of view of Europe or anywhere else but your own. It’s a discovery of your own identity.

“I think cinema is probably one of the best ways for this search to find your roots … technology has given us an incredible opportunity to preserve it. This project is a testimony to that.”

Friday, July 7, 2017 in Arts and Social Sciences, Film, International

Share: Twitter, Facebook