By Elizabeth Howell

Photos by Luther Caverly

Two Carleton researchers have received a prestigious grant from the Ontario government. The $150,000 Early Researcher Awards are intended to give early-career post-secondary faculty or principal investigators a helping hand to build a research team. Both researchers also plan to bring on student researchers to help the next generation of engineers and scientists gain real-world experience. Read on to find out what the professors will do.

Carleton researcher Sonia Chiasson plans to develop educational material to help teach kids what it means to be safe online, through games with the well-known children’s online advocacy organization MediaSmarts.

Online Safety for Kids

While children access the Internet from toddlerhood, security protocols haven’t caught up yet to protect them. Sonia Chiasson, Canada Research Chair in Human Oriented Computer Security and an associate professor from the School of Computer Science, talks to parents who are concerned about online safety for kids. “For example, they tell us: we have to use simple passwords because the kids forget them, or they don’t know how to spell them,” she said.

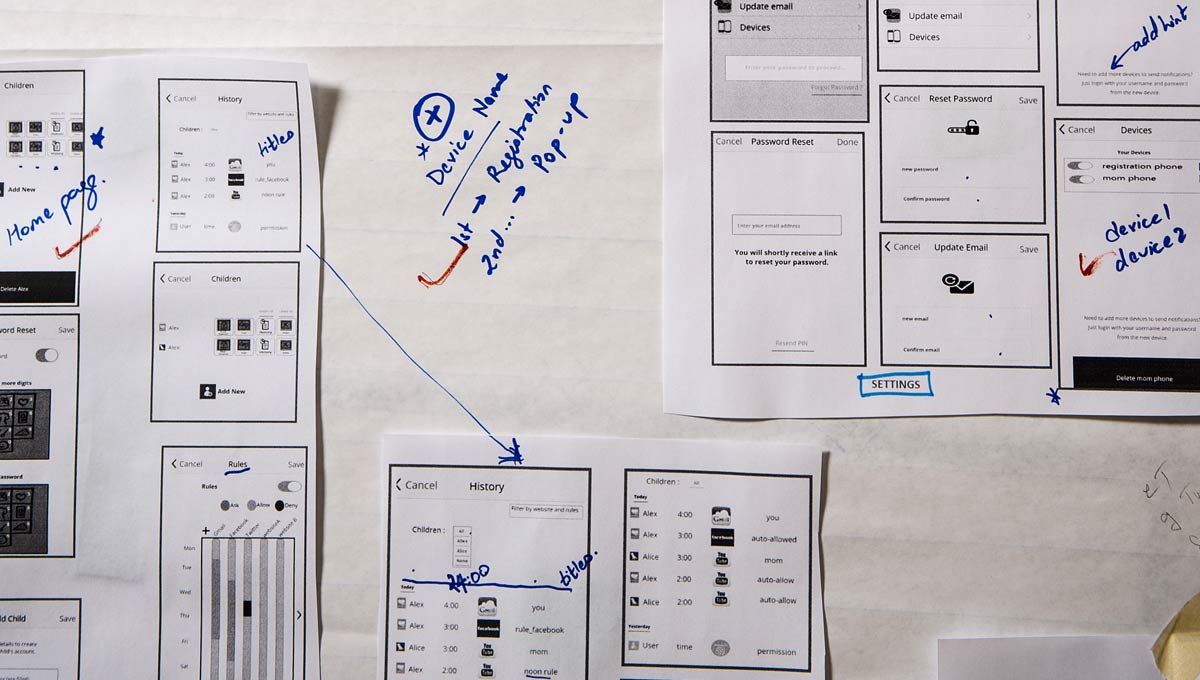

Better passwords, perhaps through the use of images and simple text, are one of the things Chiasson will research with the award funds. She also plans to develop educational material to help teach kids what it means to be safe online, through games with the well-known children’s online advocacy organization MediaSmarts. Additionally, Chiasson plans to build security and privacy tools that will let the parents change the controls as the child ages and becomes smarter at navigating online.

Chiasson’s team has just finished running a user study on a new parent-child password manager. The trial system sends notifications to parents’ phones when their children attempt to log on, enabling them to allow or deny the request. Already, parents are asking when it will be available for them to use regularly, Chiasson said.

Chiasson’s ultimate goal is to create ways that encourage and enable online safety for kids, rather than getting around standard measures for security (either inadvertently or deliberately). She also wants to ease parental concerns about children’s Internet use, particularly since many children go online without their parents around. Studies show that children carry Internet-enabled devices everywhere, and some of them even sleep next to a smartphone.

She added there has been little work done on online safety for kids, which is disappointing because 99% of children between ages 8 and 15 in Canada are online (outside of school situations) and often their parents don’t know how to help them.

Chiasson likened digital security skills to learning how to cross a street safely. “Children need to have online critical thinking skills and know how to be safe digital citizens, because that’s part of their everyday world.”

Smartphones and disabilities:

The next generation is (almost) here

Audrey Girouard, associate professor in the School of Information Technology

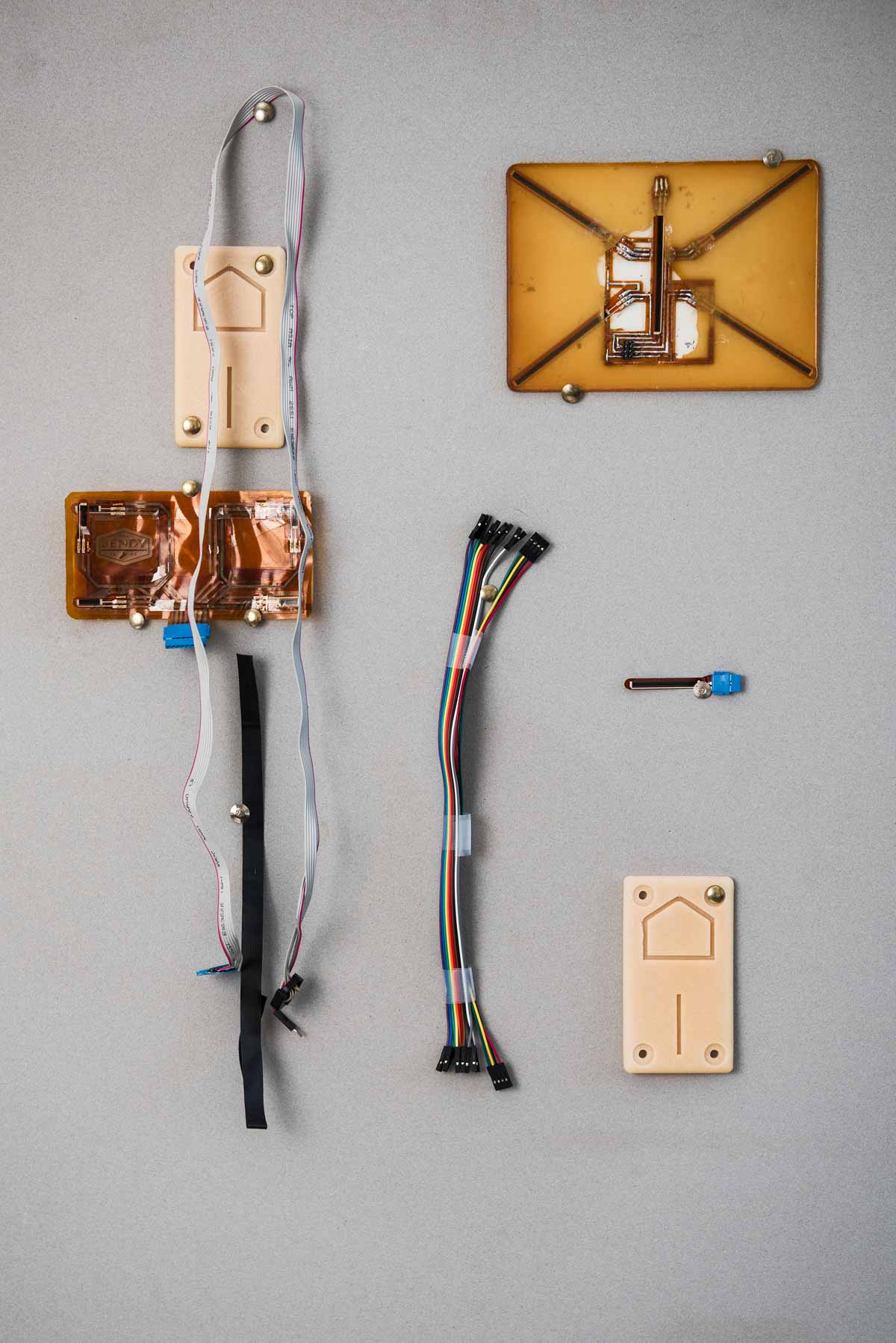

Smartphones and tablets today are rigid combinations of glass, metal and plastic. But in the future, it’s expected these devices will bend. One day, making a phone call could be as simple as squeezing your phone. Or if you’re reading an e-book, you’ll fold the corner on your tablet to turn the page.

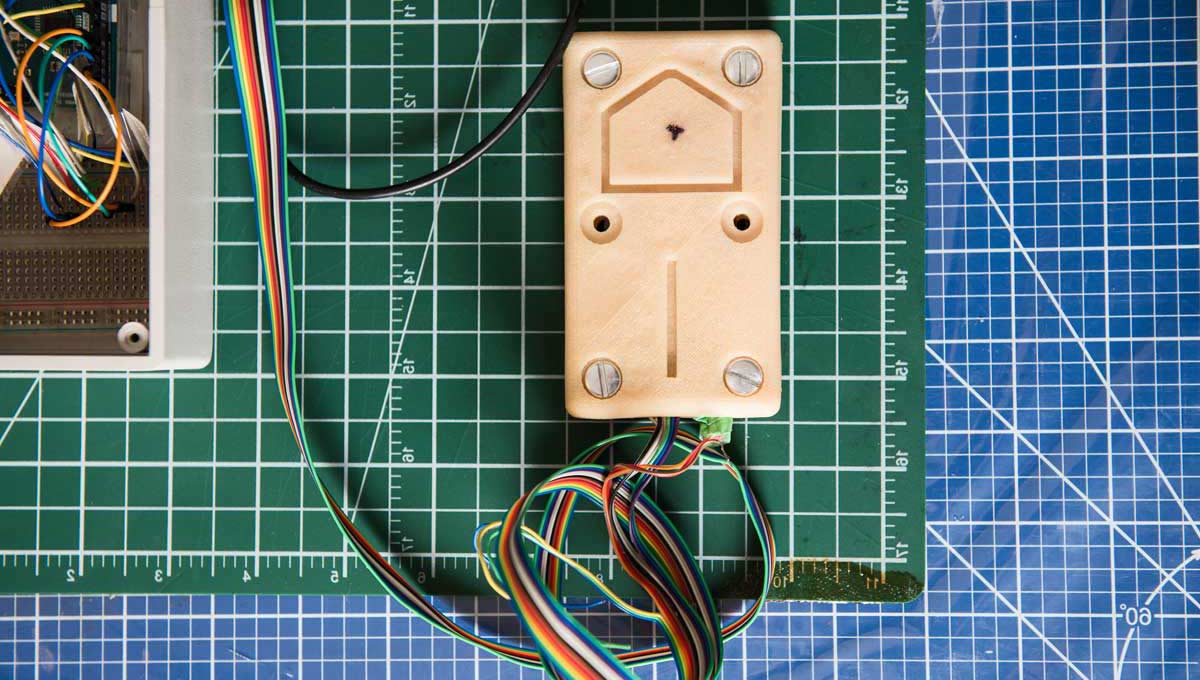

Audrey Girouard, associate professor in the School of Information Technology, hopes to use this “deformable user interaction” to help people with limited hand dexterity, perhaps through a neurological disease or common aging conditions such as arthritis. The goal is to help use these devices to improve their hand functions. The grant will help her imagine what future devices will behave best (in terms of metrics such as form factor, size and material) and to develop games and applications to keep users engaged.

“The hand is not something that therapists look at a lot,” she said. “We think that we can offer flexible devices for additional ways to do therapy, and then if you combine that with the fact that there could be flexible smartphones, this keep the patient engaged. They may be able to do their therapy at home.”

Girouard hopes to use deformable user interaction to help people with limited hand dexterity, perhaps through a neurological disease or common aging conditions such as arthritis.

In an ideal world, she added, these devices could be adapted over time after patients consult with their therapists, who would also monitor the patients’ progress (perhaps through the device itself, or through other means). This work on tablets could help patients with tasks that can be a struggle to those with limited hand dexterity, such as turning a screwdriver or removing a bottle cap.

Girouard is also head of Carleton’s Creative Interactions Lab, which looks at ways of developing input for flexible devices. Some of the lab’s recent work includes creating flexible smartphones, designing bend gesture classification, and finding cheap ways to create flexible devices. Members also have created several applications with physical dexterity built into them, such as creating “bend passwords” to enhance the usual ones typed into a phone or tablet.

Wednesday, November 23, 2016 in Accessibility, Innovation, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook