By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Justin Tang

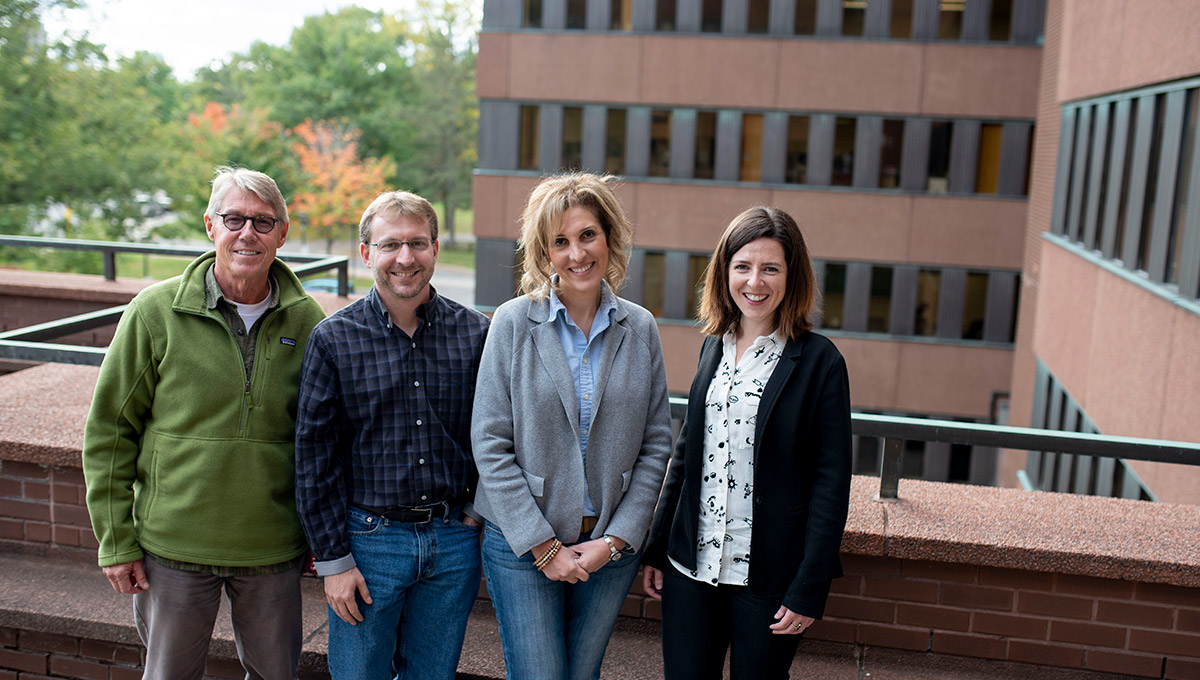

When students taking Psychology courses at Carleton have a problem in the classroom, the issue, if it can’t be resolved with their professor or the undergraduate chair, eventually reaches the office of departmental chair Prof. Joanna Pozzulo.

Over the years, Pozzulo has come to understand that these situations — both among undergrads and grad students — may be associated with underlying mental health concerns.

This past summer, she started talking to Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Dean Pauline Rankin about this pattern, asking what the department could do — a workshop? a speaker series? — to help students.

“The idea just kind of grew from there,” Pozzulo says about Carleton’s first Psychology Mental Health Day, on Oct. 18, which is aimed at raising awareness, providing education on mental health issues and promoting wellbeing, with the ultimate goal of connecting the university community to resources both on and off campus.

Prof. Joanna Pozzulo

“It has turned into something much bigger than what we thought it would be,” says Pozzulo, the event’s main organizer.

“A large number of people wanted to participate, which speaks to what’s going on all around us.”

Carleton offers a wide range of mental health services to students, faculty and staff, including counselling for students struggling with problems such as anxiety, depression or academic stress through Health and Counselling Services, and a variety of wellness and support resources through the Mental Health and Well-Being website.

Psychology Mental Health Day will not duplicate these services. Although attendees will hear practical tips on how to cope with the stress that results from procrastination, shyness and cyberbullying, among other concerns, the day is also an attempt to bridge the gap between academic research and wellness services. The expertise of the department and its community partners will allow Carleton to share valuable information that can be applied to our daily lives.

Recognizing the Mental Health Challenges People Face

The Oct. 18 event, which is free and open to the public, will begin with remarks from Rankin and Vice-President (Students and Enrolment) Suzanne Blanchard, who will provide an overview of Carleton’s many mental health initiatives.

Pozzulo will then moderate an opening panel on “Mental Health Today,” featuring Tarry Ahuja from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, Kim Corace of the Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre, Carleton Psychology instructor Kim Lassiter, Carleton equity advisor and sexual assault support coordinator Bailey Reid, Terri Soukup from the Distress Centre of Ottawa and Region, and Wabano Centre mental wellness director Marianna Shturman.

“It feels to me that over the 18 years I’ve been at Carleton, there has been an increased recognition of the many mental health challenges that people face,” says Pozzulo.

“Many institutions, such as Carleton, have worked very hard to eliminate the stigma associated with mental illness, so it’s easier for people — including our students, faculty and staff — to ask for help. Yet, not everyone does.”

Regardless, Pozzulo says that responding in a holistic way — by providing education and sharing strategies that foster resilience — is how her department can “continue the conversation about how we can all contribute to Carleton being a healthy community.”

Examining Stress and Coping

Psychology Mental Health Day will wrap up with a keynote address on stress and coping by Owen Kelly from the Ottawa Institute of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, followed by a reception in the Tory atrium. (For detailed info on the schedule and room locations, please see the agenda.)

During the lunch break, there will be wellness stations on the second floor of the Loeb Building, including Carleton therapy dog sessions, presentations from the Royal Ottawa Hospital and Ottawa Public Health, chair massages and healthy food sampling.

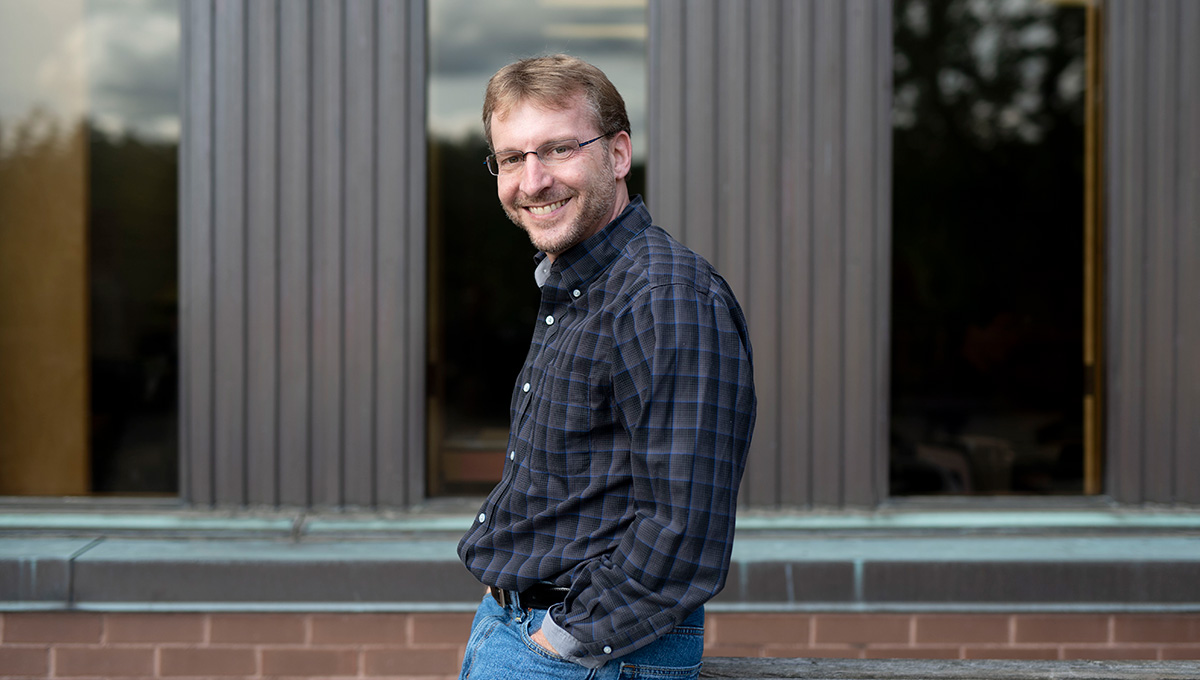

The bulk of the day will consist of workshops, many of which will be led by faculty members from the Dept. of Psychology, including Prof. Tim Pychyl, director of the university’s Centre for Initiatives in Education and one of the world’s foremost experts on procrastination.

Pychyl, whose research explores the relationship between procrastination and health, will talk about why we delay difficult tasks that we know we’ll have to do eventually, and how these deferrals create stress that undermines our wellbeing.

“We prefer short-term rewards — we want to feel good now,” he explains.

“Procrastination is not a time-management problem. It’s an emotion-management problem. We delay and delay, which ultimately catches up to us.”

This tendency is often why students cram or “binge work” to finish a project or study for an exam, says Pychyl — a practice that undermines positive behaviour such as proper sleep, exercise and a healthy diet.

Moreover, he has observed an increase in procrastination in recent years, in part because of digital technology and social media — “because the tools for distraction are always just a fingertip away.”

This risk was evident as early as 2001, before today’s fast internet and smart phones emerged. In a paper published that year, Pychyl concluded that people spent half of their time procrastinating while using a computer.

“Why does our present self screw over our future self?” he asks, noting that our wellbeing, not grades, are the biggest casualty of procrastination, and promising to share practical tips on how to avoid the habit during his workshop.

Focusing on Behavioural Change

Psychology Prof. Rachel Burns, whose research focuses on behaviour change, will lead a workshop on engaging in healthy behaviour, which can influence our psychological wellbeing.

Most of us frequently intend to eat better or exercise more, says Burns, but we find the follow-through challenging.

The reasons for this dissonance vary by individual. Some people have established patterns that are hard to break from. Others are motivated by instant gratification or their sensory experiences in the moment. We go for that freshly baked cookie, instead of an apple, because it will make us feel good right away or because it smells delicious.

But there are strategies that can help us implement healthy behaviours, says Burns, such as writing down “implementation intentions” that can guide us when we’re confronted with barriers to our goals, or by removing temptations — putting that bowl of candy in a drawer, for instance, instead of leaving it visible on the counter.

“As psychology researchers and educators, we spend a lot of time thinking about mental health and wellbeing,” says Burns.

“Participating in workshops like the ones at Psychology Mental Health Day is an important extension of our teaching and research.

“We have a lot of expertise in areas that are related to wellbeing, but are not necessarily clinical psychology. We can share what we know to help individuals in their daily lives and contribute to the broader conversation surrounding psychological wellbeing.”

Public Outreach a Primary Goal

Psychology Prof. Robert Coplan, who researches the development of shyness, social withdrawal and social anxiety in childhood, says that public outreach such as the Psychology Mental Health Day should be one of the primary goals of his discipline.

“Psychologists can do a lot more with our research,” he says.

“We’re trained to be cautious about our research results and how they apply to the real world, but there’s so much information out there that’s not based on any research.”

Coplan agreed to co-author a book called Quiet at School: An Educator’s Guide to Shy Children, for example, because he was told that if he didn’t contribute to the discourse around this important issue, somebody with less knowledge likely would.

Shyness is a misunderstood personality trait, says Coplan, and has a lot of negative connotations. Students who are quiet in a classroom can be perceived as less intelligent or unprepared by teachers. Teachers may also pay them less attention because they are more focused on acting out children, who disrupt the classroom and interfere with learning. Modern pedagogy was not developed with shy people in mind; grades often incorporate marks for verbal participation, group work and the dreaded in-class presentation.

But shy people may be quiet in class because they’re uncomfortable or nervous about speaking in larger groups, or appear inattentive because they are ruminating about the possibility of being called upon to answer a question.

“These kinds of challenges are embedded into the curriculum,” says Coplan.

“Shyness can make students more vulnerable to these sources of stress, which in turn can lead to academic difficulties, which can lead to more stress. Stress can also further exacerbate shy students’ feelings of anxiety which, if left unchecked, can deteriorate into more serious mental health difficulties.”

Coplan’s workshop is part of his attempt to raise awareness about shyness. His most important message is that the onus should not be only on students to communicate their concerns to their professors, nor on just their professors to accommodate individuals with unique needs, but that a collaborative effort is required.

“There are a lot of positive aspects associated with people who are shy,” he says. “It’s important that there are people in our population who think before they act and are perhaps more sensitive to threats in our environment. But because our how society has evolved, there are demands that are social in nature.

“We shouldn’t try to change who people are,” adds Coplan. “We simply need to equip people with knowledge and the necessary coping strategies.”

Wednesday, October 10, 2018 in Accessibility, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Mental Health, Psychology

Share: Twitter, Facebook