By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Fangliang Xu

Spending time alone is like exposure to direct sunlight. We all need some of it, but too much can be unhealthy — and everybody’s threshold is different.

Researchers call this the paradox of solitude, and it has become a key part of the conversation about mental health throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, when people are experiencing the extremes of both unwanted isolation and crowded households without enough personal space.

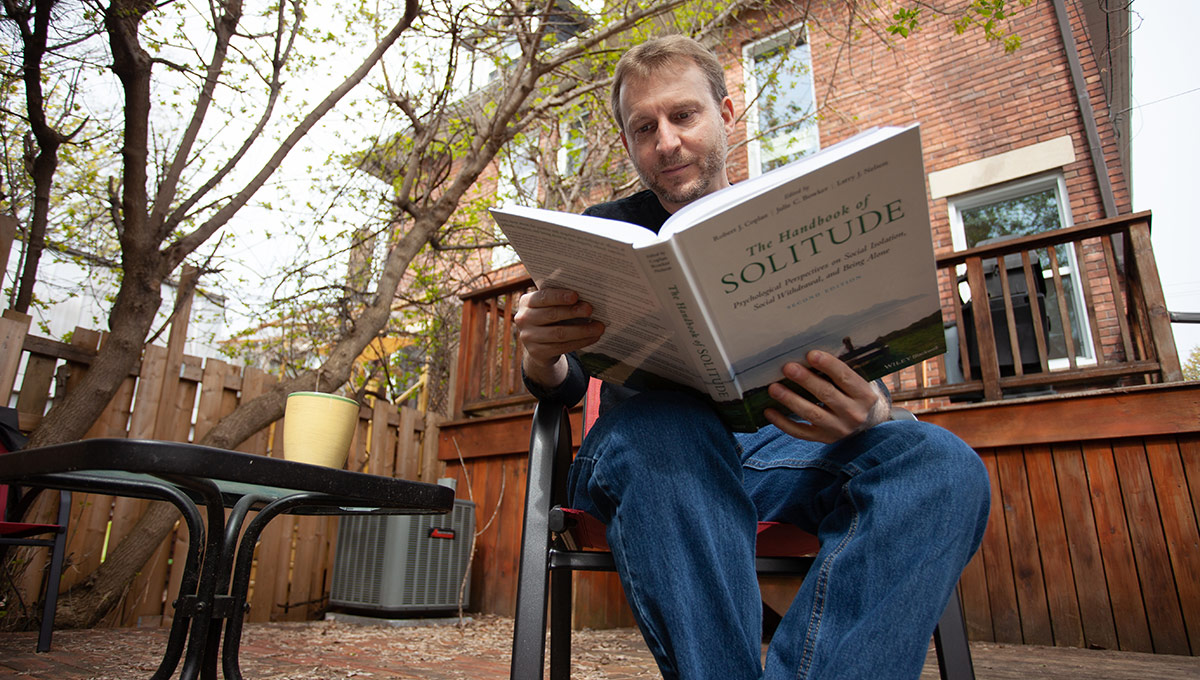

Prof. Robert Coplan

“There’s never been a more important time to study solitude and its implications,” says Carleton University Psychology Prof. Robert Coplan, a leading international expert whose work has received a surge of interest.

“Historically, solitude has a pretty bad reputation and is seen as the cause of a lot of problems. Loneliness is a mental health issue; it can lead to anxiety and depression and even impact physical health. It’s a real concern.”

“But you can’t paint all solitude with the same broad brush,” he continues. “It can also be good for us. It can help with self-understanding, serve as a context for restoration and promote creativity.

Yet not all people like it. One experiment in the United States found that most college students would rather receive a painful electric shock then spend 15 minutes by themselves with nothing to do but think.

There’s a tremendous difference, in other words, between somebody seeking “me time” and a prisoner sent to solitary confinement.

“If solitude is imposed on you,” says Coplan, “that can have profoundly detrimental consequences.”

Topic Gets New Attention

Nine years ago, when Coplan and a pair of collaborators decided to put together the first academic book about solitude, they had to convince people that it was a worthy subject.

Last month, the second edition of The Handbook of Solitude, co-edited by University at Buffalo Prof. Julie Bowker and Brigham Young University Prof. Larry Nelson, was released, updated with COVID-informed content that explores the links between spending time alone and well-being.

The Handbook of Solitude

“We started investigating solitude and social isolation long before it became something that everybody’s interested in,” says Coplan, whose research has been thrust into a media spotlight.

In recent months, he has been interviewed by the New York Times, NPR, Vice and the popular health information website WebMD, among others.

But it was a new term that Coplan came up with about three years ago — “aloneliness,” the feeling that arises when one’s need for solitude is not met — that has generated the most unusual attention.

With so many people experiencing aloneliness these days, the producers of a TV game show — the German equivalent of “Who Wants to be a Millionaire?” — used it as a clue in one of their episodes.

“There’s been more awareness about aloneliness during the pandemic,” says Coplan, who published the first two papers on the topic in 2019 and January 2021, “but that was definitely the quirkiest response I’ve ever seen to my work.”

Defining Solitude Amid High-Tech

Coplan, whose research shifted toward solitude from earlier studies on shyness and social withdrawal during childhood, is collaborating on projects in Shanghai, Rome and Oslo.

He’s wrestling with foundational questions such as how to define solitude in an era when the phone in your hand can instantly connect you to people near and far.

There are no firm parameters, says Coplan: How physically apart from others do you have to be to be considered alone? Is there a difference between reading online and engaging in conversations on social media?

“Solitude has so many nooks and crannies,” he says. “To unravel this paradox, you need to ask a lot of W questions — who is alone, where, when and why? — and probe a lot more deeply.”

Coplan’s advice for people who need alone time to alleviate stress is to take advantage of “micro moments,” such as walking around the block which can be enough of a reset.

As a species, humans typically fare better when we interact with others.

In one European study, people with a range of personalities were seated either by themselves or beside others on an hour-long commute. Regardless of individual tendencies, those who spent the time chatting were in a better mood at the end of the train trip.

If you’re cut off from others and crave contact, scheduling video calls and other interactions may be the only way to make up for the spontaneous encounters that would take place in normal times.

It may not be the same, but it could tide you over.

Coplan experienced this phenomenon first-hand when he recently received the Pickering Award for Outstanding Contribution to Developmental Psychology in Canada.

The March 2021 ceremony was a virtual one and Coplan was initially disappointed that he’d be sitting at home in front of his computer. But when his parents, siblings, collaborators and former students joined the online event from around the world, he realized that he was far from alone.

Wednesday, May 5, 2021 in Mental Health, Psychology, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook