By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Justin Tang

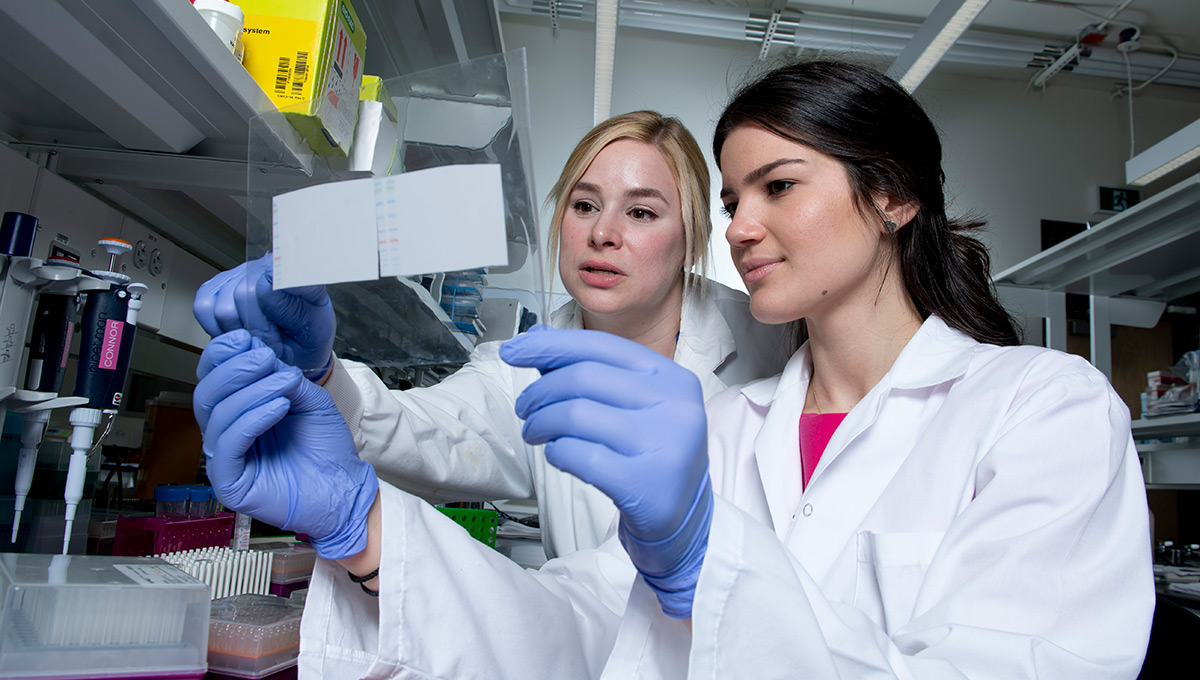

Wearing a white lab coat and blue nitrile gloves, Carleton student Elia Palladino sits at a bench in a large open-concept laboratory on the third floor of the university’s new Health Sciences Building, painstakingly using a pipette to squirt six microlitres of a synthetic dye solution into each of the 384 tiny compartments in a rectangular plastic plate.

Palladino, a third-year Health Sciences major, is chipping away at an experiment that’s investigating the impact of maternal malnutrition on the transfer of B vitamin folate and the pseudovitamin inositol from mother to fetus through the placenta. Low levels of folic acid in the mother are linked to poor fetal growth and neural tube defects — which hinder brain and spinal development — and other long-term concerns.

But to understand the intricate relationships between maternal diet, fetal development and offspring health, and to develop interventions that can be used before or during pregnancy to reduce the risk of birth defects and other fetal complications, researchers have to design and complete a series of rigorous experiments to produce the data they need to validate their theories.

Sebastian Srugo and Elia Palladino

Across the aisle from Palladino and wearing matching lab attire, fourth-year Health Sciences student Sebastian Srugo is using a pipette to prepare solutions containing different sequences of DNA for the PCR machine, a “thermal cycler” that uses heat to amplify and measure the amount of DNA in biological samples.

Srugo’s studies, which have been under way for nearly two years, explore the development and function of the fetal and maternal guts, and could help us understand how gut defences develop in early life and how the gut communicates with the brain.

If the fetal gut has too few cells that produce antimicrobial peptides (part of the innate immune system that protects us from infection) or too few enteric glial cells (which help regulate inflammation and are a key part of the gut-brain axis) there could be implications for our immune defences and for brain development and function. The long-term consequence may be greater vulnerability to brain-associated disorders such as autism and, as we age, dementia and Parkinson’s disease.

“This research could give us important information about connections between diet during pregnancy and fetal health, as well as the long-term risk of chronic disease,” says Srugo, who has to do each time-consuming step of the experiment in the exact same way to ensure the results are sound. “The circumstances we encounter in utero could be setting us up for poor future health.”

Searching for the Developmental

Origins of Health and Disease

Both Palladino and Srugo — who frequently make disclaimers such as “correlation is not causation” — are supervised by Health Sciences Prof. Kristin Connor, whose research focuses on the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD). Palladino, in fact, was Connor’s first student when she joined the faculty at Carleton in September 2015, just one year after the university launched its Bachelor of Health Sciences degree.

The two undergraduates are not only helping a relatively new professor and relatively new program advance the frontier of health research, they also represent a new interdisciplinary approach to health sciences education that’s part of a bold holistic attempt to find solutions to some of today’s most critical health issues.

Connor’s research epitomizes the ethos of Carleton’s Health Sciences Department, where work spans the spectrum from wet lab biomedical research to epidemiology, with a web of collaborations among experts in fields such as chemistry, clinical medicine, computational biology, neuroscience, health policy and regulatory affairs.

Prof. Kristin Connor

Thousands of complex and interconnected mechanisms impact our health, including genetics, lifestyle, the socio-economic conditions we live in and myriad other factors, including what our mothers eat and their exposure to environmental toxicants when pregnant.

Instead of waiting until ailments or diseases arise and countering them with expensive and potentially side effect-inducing pharmaceuticals, early preemptive measures — for instance, programs that encourage people to make simple changes to their diets and daily routines — can have a much more effective and sustainable impact.

But this is a major shift away from our quick-fix emergency room medicine and drugs mindset. Strategies to prevent diseases or lessen their burden must be rooted in compelling scientific knowledge that takes into account the many determinants that shape our health. Which is why Connor and her colleagues, although trained in specific disciplines, want their students to look at health issues from every possible angle.

“I’ve always been interested in preventative medicine and the idea that nutritional and lifestyle factors, and the biological, social and physical environments we’re exposed to early in life, profoundly affect our health trajectories,” says Connor.

“Where we end up is a byproduct of where we start from, and you can’t understand or improve health through one lens. It’s about doing small things that cumulatively will have a greater impact.

“We, the faculty in Health Sciences, were not trained as interdisciplinary researchers when we came up through the academic system. But our job is to graduate interdisciplinary thinkers. We expect our students to go off in boundary-blurring directions. But you can’t do interdisciplinary education without disciplinary expertise.”

Pursuing Interests in Nutrition, Nature and Biology

Connor was born and raised in Stratford, Ont., where she had an active childhood, transitioning from years of ballet to basketball and badminton in high school, along with plenty of hiking, camping and kayaking with her family on Georgian Bay.

Playing sports spurred an interest in nutrition, and all that time outdoors inspired an affinity for nature and biology, so Connor majored in Molecular Biology and Genetics at the University of Guelph, with a minor in Nutritional Sciences. She had been planning to go to medical school, but her undergraduate studies were research intensive, and she fell in love with having the freedom to ask and seek answers to any question as a scientist, rather than stick to a more confined framework as a clinician.

Connor went on to do a PhD in Reproductive and Developmental Physiology at the University of Toronto, supervised by John Challis, an international expert in fetal physiology and pre-term birth whose lab was conducting research on undernutrition during pregnancy and other work.

This direction captured a lot of her personal interests, and Connor had the technical skills from her undergrad to do the type of hands-on lab work that Palladino and Srugo are now mastering. Moreover, Challis had studied under leaders in fetal physiology and was part of its evolution into the exciting new field of DOHaD.

These connections sent Connor to New Zealand, Australia and the United Kingdom during her doctoral studies — “global hotspots for DOHaD research,” she says — and helped her land a postdoctoral fellowship at the Liggins Institute and National Research Centre for Growth and Development in Auckland.

“It’s crucial to have a good mentor,” says Connor, who followed two-plus years in New Zealand with four years as a research fellow at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital with Stephen Lye before taking her current post at Carleton.

“It’s crucial to have a good mentor,” says Connor, who followed two-plus years in New Zealand with four years as a research fellow at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital with Stephen Lye before taking her current post at Carleton.

“You need to have people who believe in you and trust you and train you, and then give you independence and know that you’ll go out and do science that excites you — and do it well.”

The guidance that Connor received from Challis and Lye, a pre-term birth and pregnancy complications expert at Mount Sinai whose DOHaD research group she was recruited to lead, set the tone for how she works with students at Carleton. They must contribute to her research, including ongoing collaborations with Mount Sinai, but also have to put their own spin on it.

“My research can’t grow without input from a variety of viewpoints,” says Connor. “That’s why I put so much time and effort into working with undergraduates. It takes them a long time to do things, and they make mistakes. Despite this, they bring new perspectives on the world and to the problems we face, so we can learn from each other.

“Committing to them and their training empowers them to be the creative scientists we want to help develop, and allows them to see that their insight is valuable to what I do. I don’t take students into my lab to do make-work projects. They contribute to real-world research. There are tangible outputs.”

Cultivating Research Communication Skills

Strong communication skills are another tangible output that Connor wants to cultivate among her students.

It’s one thing for a young researcher to understand a complex scientific idea; explaining it to a general audience can be extremely challenging. But if the overarching goal is to help shape public health policy and improve health across the country and around the world, you need to be able to distill technical concepts into everyday language.

Connor demonstrates the value of communication on her lab’s website, connorlab.ca, with graphic icons and detailed – yet not overly dense – language. And before Palladino and Srugo accompanied her to late-winter conferences in San Diego and Banff respectively, they practised their presentations — for Palladino, a poster presentation; for Srugo, a 10-minute talk — during lab meetings.

These efforts paid off. Srugo’s conference talk, to a diverse group of obstetrician-gynaecologists, neonatologists, paediatricians, governmental health officials and research scientists, beat out graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and clinical trainees to win the best oral presentation award at the annual Canadian National Perinatal Research Meeting.

Carleton’s Health Sciences Building. Photo by Matt Gergyek.

“Sebastian said to me: ‘Now I understand why you had me change my slides five times,'” laughs Connor. “Details matter. These types of science communication opportunities help put the university on the map.”

Connor’s focus on undergraduates may seem unusual, especially for a professor who is not only pursuing her own research and teaching, but also helping Carleton shape its Health Sciences program, launch graduate studies streams and move into a brand new building. Yet she sees all of these responsibilities as pieces of the same puzzle — just as she sees human health as an integrated state — and has learned how to be “fiercely protective” of her time to be able to do the deep thinking her research requires.

One of Connor’s projects involves analyzing data from the Maternal-Infant Research on Environmental Chemicals (MIREC) study, a massive Health Canada and Canadian Institutes of Health Research biomonitoring project that examined potential adverse health effects of prenatal exposure to environmental chemicals in 2,000 Canadian women and their infants in 10 cities from 2008 to 2015.

Connor and her MSc students in Carleton’s Health: Science, Technology and Policy program are working to determine how maternal weight, weight gain in pregnancy and exposure to heavy metals while pregnant are related to the cognitive development of infants, and how breastfeeding might serve as a protective intervention. They are also doing a social media data mining study as part of this overall effort.

Research Opportunities for Health Science Students

Her other key project, funded in part by a new investigator grant from the Molly Towell Perinatal Research Foundation, is looking at women who are underweight or obese during pregnancy, conditions that are associated with inflammation, which in turn is associated with pre-term birth and adverse fetal outcomes.

This research is zeroing in on the placenta, which serves as a conduit for nutrients, oxygen and other substances to reach the fetus and shape its development.

Placental function is diminished by inflammation, which is why Connor thinks being underweight or having obesity may also diminish natural defences in the placenta and fetal membranes. This may explain in part why weighing too much or too little is associated with greater risk of pre-term birth and suboptimal fetal development.

The placental research, some of which involves Palladino, makes use of both animal models (mice) and human tissue samples from pregnancy cohorts at Mount Sinai. Palladino has been able to demonstrate that if a mouse is undernourished during pregnancy, folate production and transportation is affected, which impacts fetal development.

Taking probiotics (because they play a critical role in the production of some vitamins) could be a remedy that increases folate production in the maternal gut, which could then be transported to the fetus through the placenta.

Srugo’s project, although completely separate, is similar in that he is exploring how malnutrition can alter the gut, including the microbiome (or community of microorganisms), which impacts gut integrity and function. This work has implications for the health of both pregnant women and their children.

“We think this may be related to early brain development,” Connor says about Srugo’s research, “because the gut and the brain talk to each other.”

A dysfunctional offspring gut microbiome, she suggests, could lead to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and anxiety and depression later in life.

“We’re trying to understand how these systems are formed, how our future health pathways are created,” says Connor, referring specifically to the work her students are doing, but also thinking about her entire research program.

“We want to prevent this type of adversity in the first place. The cells that eventually make up the embryo and fetus develop and multiply, starting even before conception.”

Paying more attention to maternal health — as part of a broader attempt to improve the long-term prospects for children — may seem intuitive. “But in my field,” says Connor, “there’s a very high burden of proof to convince people that what happens in very early life is linked to our health in later life. Because you might not see the positive outcome of an early-life intervention for 30, 40 or 50 years. Most people understand that if you get cancer, for example, there are treatments and drugs. They don’t understand preventative medicine in the same way.

“The average person may look at connections between research and public policy or lifestyle interventions in a different way than scientists,” adds Connor, “but we always have to keep the bigger picture in mind. Ultimately, this is our obligation as scientists. We’re relying on public money to try to help people remain healthy.”