By Dan Rubinstein

In mid-March, when Carleton University cancelled face-to-face classes and moved to alternative modes of instruction for the rest of the term, third-year Journalism student Sarah MacFarlane left the city to be with her family near Winchester, south of Ottawa.

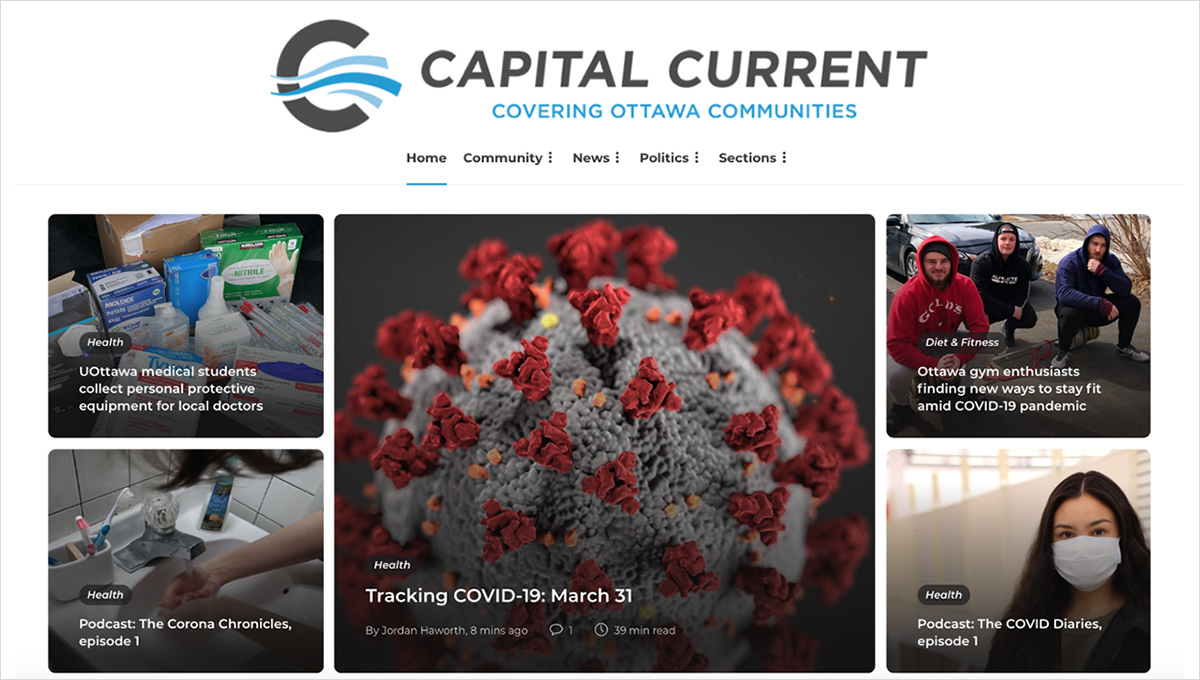

One of the classes she’s completing is focused on digital journalism, with students pitching stories that frequently end up getting published on Capital Current, the program’s flagship online publication. Prof. Allan Thompson, who works with students as their editor, suggested they look for issues related to COVID-19.

Sarah MacFarlane

Back home, MacFarlane noted the impact of the pandemic’s social distancing restrictions on churches and faith-based communities that are a huge part of the social fabric of her rural part of the province.

“It can be a tremendous comfort to get together at a time like this,” says MacFarlane, who is using the phone and Internet to work on an article about how churches and other religious organizations are using technology to adapt to the new normal.

“Some churches are very technologically savvy and can make the switch,” she says, “but it’s a very complicated process for those that are more traditional, and some people really need what they’re able to provide.”

Because church congregations tend to be older, parishioners may not be familiar with connecting online. Yet from Facebook pages to livestreaming services, whether it’s something they’ve done for years or a brand-new practice, churches are finding ways to offer reassurance and community.

MacFarlane and her classmates are not only sharpening their journalism skills by reporting these stories, they’re also disseminating important information that mainstream media outlets may not be able to cover with so much happening. And they’re keeping themselves engaged in the world during a time of unprecedented uncertainty, when there’s a risk of drifting toward feelings of helplessness and fear.

“This is giving me a sense of purpose,” says MacFarlane. “This is the first real dramatic shift in society that I’ve been a journalist for, and this is the type of situation when people rely on journalism. It’s a duty and a public service, and I have an opportunity to contribute.”

Talking to Sources from Afar

Thompson, a veteran journalist who covered the aftermath of the genocide in Rwanda, describes JOUR 3235 as a fairly typical third-year reporting class, so he asked students to pitch stories “that relate to the thing that everybody is talking about,” with clear instructions to only interact with sources online and over the phone.

That’s counter to the usual emphasis on seeking face-to-face interviews, and it presents challenges for acquiring images, although students were encouraged to ask people they speak with to shoot and share selfies that can be published online with the articles.

“We’ve got to finish the term and we really need students to do these assignments,” says Thompson, “so they can further develop their skills and also give me something more to assess them on.”

One of his students is working on a story about how the pandemic will impact Ramadan, which starts in late April. Another is looking at what sports media are doing with no games to cover.

Graham Swaney, an American student who is writing a feature on how homeless shelters are coping with the COVID-19 outbreak, has already published an article detailing his surreal journey to his diplomat parents’ home in the Dominican Republic after Carleton asked students to leave their residence rooms.

“We don’t have a (template) for covering a crisis like this,” says Thompson. “Typically, they don’t last for more than a few days or a few weeks, and we didn’t have a 24-hour news cycle during the Spanish Flu.

“People are sitting in front of their TVs and computers and media are finding ways to tell us what we need to know. There’s higher viewership than normal and journalists are providing an essential service. We’re not doctors or firefighters, but journalists are important.”

On one hand, journalists working on stories about traumatic situations are at risk of mental and emotional strain, adds Thompson, and we don’t know how to gauge the impact of this load. On the other hand, he says, “even in normal times, journalism is a job that makes people feel like they’re helping others by providing information that’s useful, and that can be a good thing.”

Pandemic: How the Most Vulnerable are Faring

For student Mercedes Belaiche, who is reporting on how food banks in Ottawa are dealing with increased demand with no volunteers and other challenges, the crisis is providing an eye-opening look into vulnerable populations and their supporting institutions.

“They’re still running and their doors are still open,” she says, “but they’ve had to change the way they do things.

Some clients served by food banks weren’t aware there was a pandemic, Belaiche learned, and the staff she’s spoken with said they haven’t turned away a single hungry person.

“It’s a real-world lesson for students in the journalism program,” she says. “It’s an opportunity to rise up and cover things that might be overlooked. And it’s reaffirming to me the importance of journalism: despite how busy they are, people want to talk and share their stories and demonstrate that what they’re doing matters.”

“Journalism has a way of uniting all kinds of different people,” adds MacFarlane, “especially when we’re physically separated. Journalism can remind us that we’re all human beings and are all connected to one another.”

Monday, March 30, 2020 in Health, Journalism and Communication

Share: Twitter, Facebook