By Joseph Mathieu

“If you want to learn about the Holocaust, you have to have to start understanding what you lost,” says photographer Tal Schwartz, the researcher-protagonist of the documentary Glass Negatives.

“This is, for me, what this collection has. When you look at those thousands of faces, you start to get a sense of this huge loss.”

On Jan. 27, 2021, Carleton marked International Holocaust Remembrance Day with an online commemoration that gathered students, community members, dignitaries and other guests. Schwartz and Jan Borowiec, director of the documentary, joined the virtual event from Israel and Poland to discuss their work.

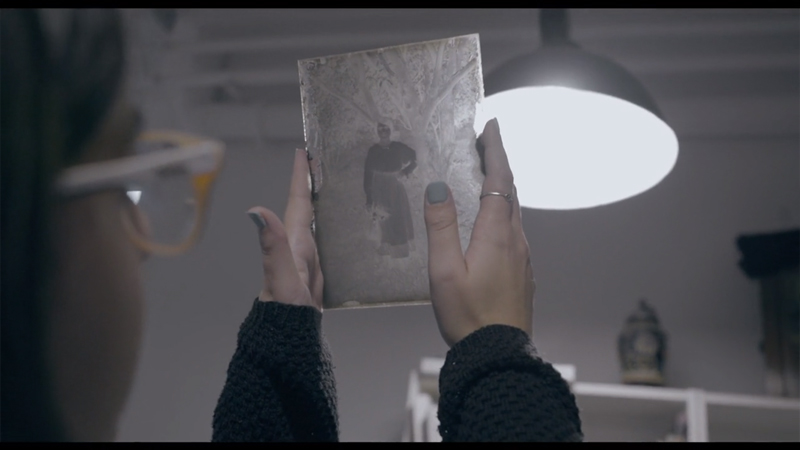

A scene from the documentary Glass Negatives

In 2012, Polish construction workers renovating a Lublin tenement found almost 3,000 glass negatives hidden in an attic.

To this day, the photographs clearly show thousands of faces from the city’s past. They are the faces of children playing with toys and of musicians posing with instruments; of families at home around the dinner table and of partying friends raising glasses. They are the faces of workers posing in uniform, of parents holding babies and of couples on their wedding days. They are the faces of girls and boys on the cusp of becoming women and men.

Many of these people were Jews, which means many of them were murdered. In Lublin, the Nazis extinguished the lives of 43,000 Jewish people during the Second World War.

The renovation crew had the glass negatives cleaned, sorted and donated to a local cultural arts and heritage organization called Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre Centre. When Schwartz and Borowiec met, they decided to investigate the collection to discover the names of the people in front, and behind, the camera.

Lost Memory, Forgotten Lessons? Holocaust Education & the Challenge of Anti-Semitism Today

Carleton Religion Prof. Deidre Butler, director of the Max and Tessie Zelikovitz Centre for Jewish Studies, and University of Ottawa Prof. Hernan Tessler-Mabé, co-coordinator of the Vered Jewish Canadian Studies Program, led a discussion with the film’s creators. The event was called, Lost Memory, Forgotten Lessons? Holocaust Education & the Challenge of Anti-Semitism Today.

Carleton Religion Prof. Deidre Butler

The evening began with the announcement of a gift of essential history books to the Carleton and University of Ottawa libraries. The Embassy of Israel in Canada offered the donation that, said Butler, “stands against the international tide of willful forgetting of the Holocaust, through Holocaust denial, minimization and distortion, and calls us to never forget the victims or the trauma of the survivors.”

Embassy of Israel Chargé d’Affaires and Deputy Chief of Mission, Ohad Kaynar, called the gift a modest effort to further the purpose of the day.

“Today we come together as a community to say no to prejudice, to say no to anti-Semitism and other forms of racism, to say no to hatred, to stand for inclusivity, for our common shared humanity,” said Carleton President Benoit-Antoine Bacon.

President Benoit-Antoine Bacon

University of Ottawa President Jacques Frémont echoed the sentiment by defining the fight against anti-Semitism as a fight against the very idea of racism and all forms of racial discrimination.

“We share a duty to speak out to remember the atrocities of the past in order to eliminate such terrible events from our future,” said Frémont.

Honouring the Survivors and the Rescuers

The event included remarks from Carleton Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Dean, Pauline Rankin, University of Ottawa Faculty of Arts Dean, Kevin Kee, and Embassy of Israel Consul Orly Erlich, a third-generation descendant of Holocaust survivors who shared her family’s stories.

FASS Dean Pauline Rankin

Irwin Cotler, Canada’s special envoy for Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Anti-Semitism, noted that while Holocaust education must showcase the atrocities of Nazi Germany, it should also honour the survivors and the rescuers of human history’s darkest chapter.

“Holocaust survivors endured the worst of inhumanity,” said Cotler, “but somehow they found in the resources of their own humanity the ability to go on, to rebuild their lives, to start families, and to make contributions to whatever community and country they became a part of.”

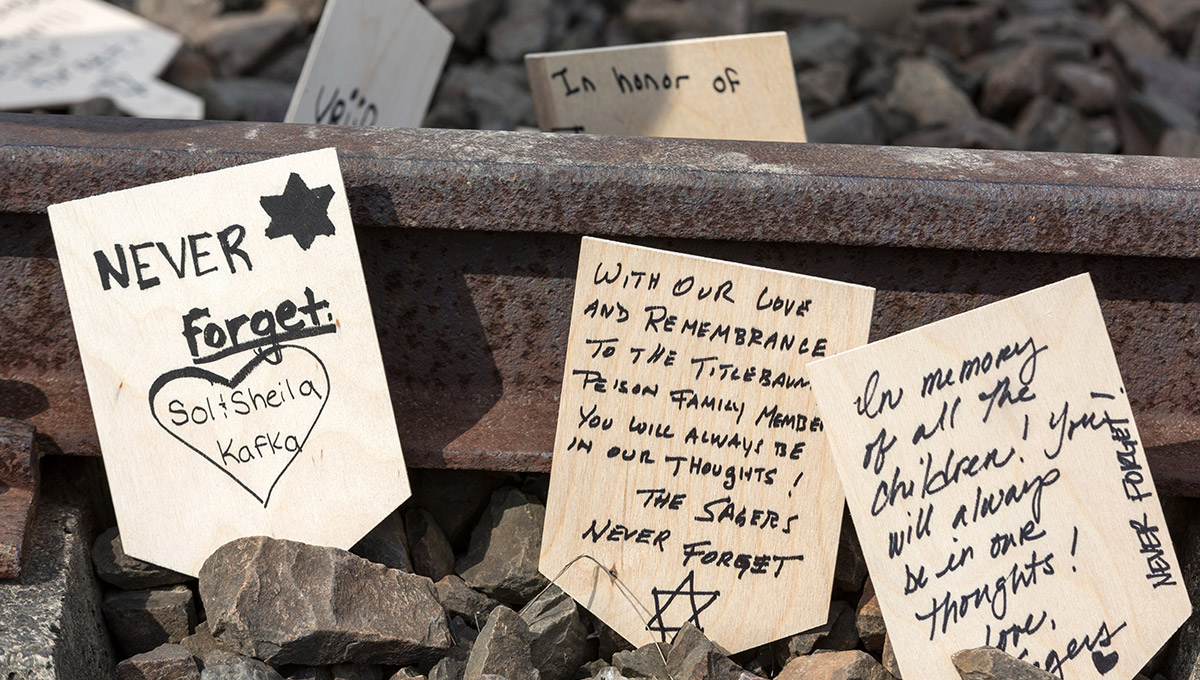

A scene from the documentary Glass Negatives

For Schwartz and Borowiec, digging into the past of Lublin wasn’t just about putting names to faces, or identifying the photographer of the glass negatives. Their journey became a storytelling about something that wasn’t entirely lost to the Holocaust.

“I hope the viewers, like us, realize that the answer to the name of the [photographer] is not the most important answer,” said Borowiec.

“The question is an answer.”

The full documentary Glass Negatives can be made available to students or community members by reaching out to the Zelikovitz Centre.

A scene from the documentary Glass Negatives

Friday, January 29, 2021 in Film, In Memoriam, Jewish Studies

Share: Twitter, Facebook