By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

Although the tools they use have evolved over the years, architects have always designed and built physical structures and objects.

A pair of jointed-arm industrial robots recently acquired by the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) represent the latest leap forward.

Roughly three metres high when fully extended, the Kuka KR 360 and a desk-sized KR 6 are housed in a customized room in Carleton’s Architecture Building. Kuka is the manufacturer and the numbers refer to the payload (in kilograms) each machine is capable of handling.

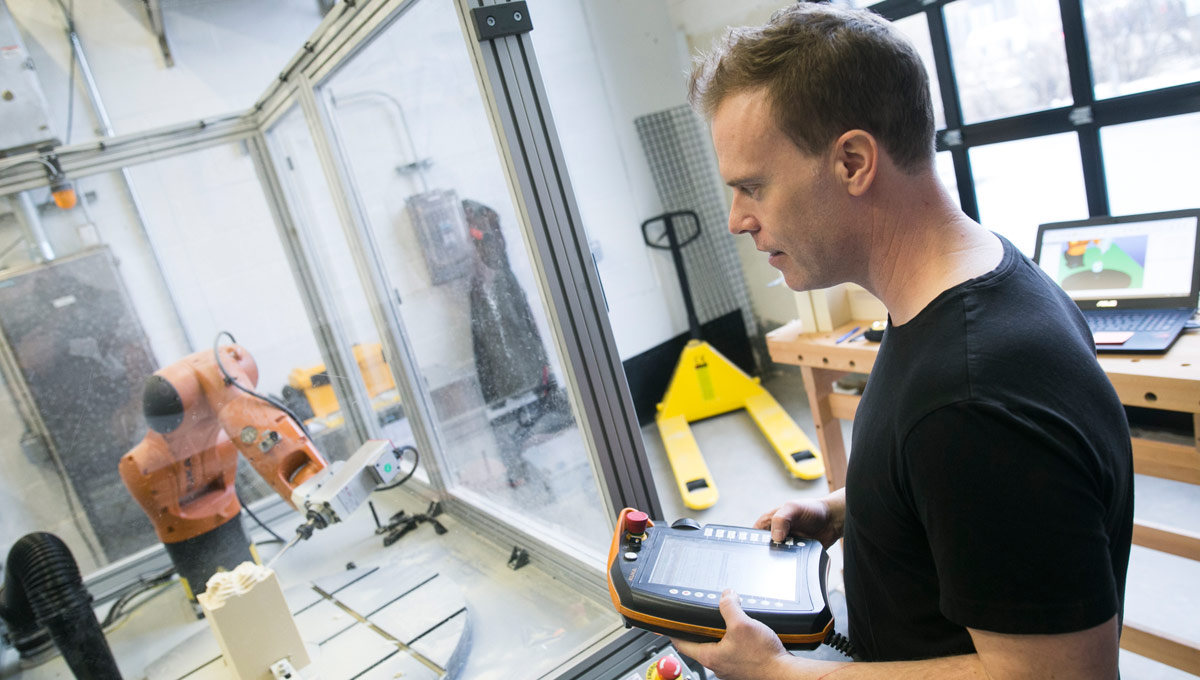

Carleton University Architecture PhD candidate James Hayes

Purchased with support from Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), the robots will help CIMS and its collaborators in the federal government continue their cutting-edge work in the rapidly advancing world of digitally-assisted fabrication.

“We’re the only university in Canada with a setup of this kind,” says James Hayes, the Architecture PhD candidate helming the robot project, currently focused on the heritage conservation components of the major rehabilitation of Parliament Hill.

“The ability to actually craft and make artifacts is fundamental to an architectural education.”

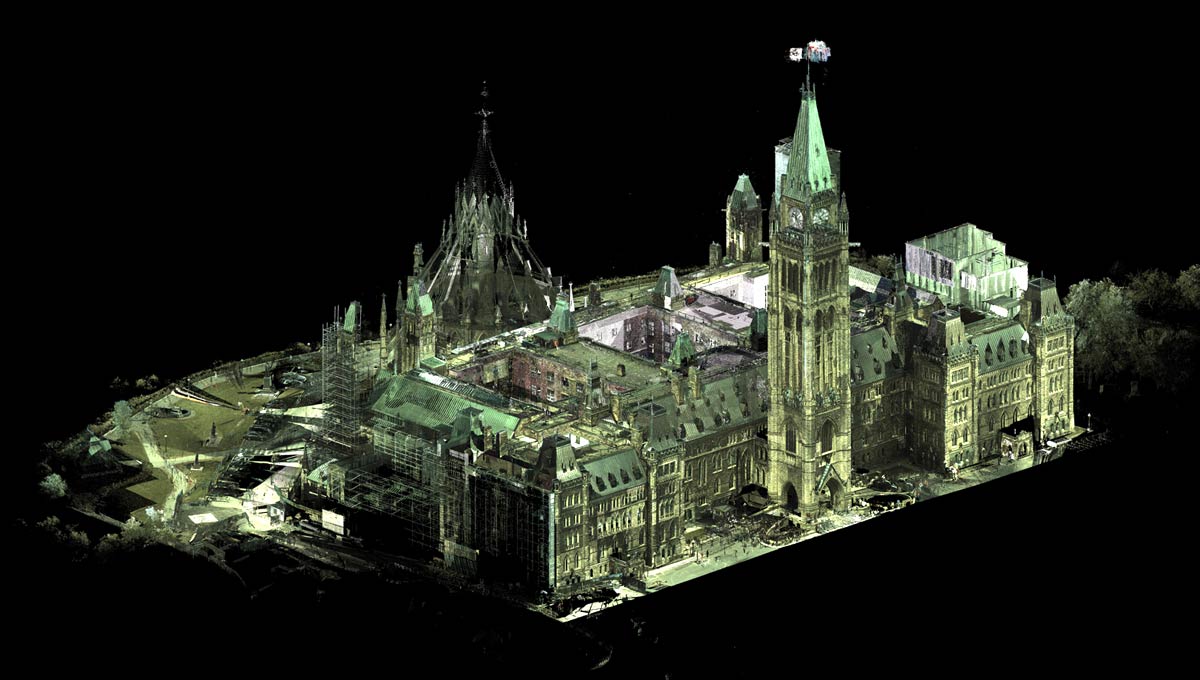

The CIMS team will use the robots to assist in creating sculptures and other architectural ornaments in a variety of materials — including stone and wood — from digital models obtained by laser scanning and photogrammetry, the science of using photographs to make precise measurements.

This technology has already been of use on Parliament Hill, where centuries-old sculptures are being replaced or restored as part of the renovations, and new decorative features are being crafted for the Government Conference Centre, which will serve as a temporary home for the Senate when the decade-long Centre Block restoration begins next year.

And because human hands will continue to play a role in this process, from operating the robots to the fine-detail finishing work on a sculpture before installation, some people in traditional fields such as stone masonry don’t see the robots as a threat to their employment.

A Tool in the Tool Box

“They’re another tool in the box,” says Canada’s Dominion Sculptor Phil White, whose responsibilities include the conservation of all the architectural ornamentation on Parliament Hill. “From my point of view, this technology is going to enhance the possibilities for what we can do.

“I don’t see people losing jobs,” continues White, noting that there is some concern and debate in his field about the impact of new technologies.

“There could even be new jobs created. Digital fabrication provides an opportunity to learn a new craft in combination with a traditional craft.”

Laser scanning something as a step toward making a 3D object is an idea that developed at the National Research Council (NRC) in Ottawa in the 1990s, says White, who was working at the Museum of Civilization at the time and worked with the NRC to create a replica sphinx for an Egypt exhibition.

Two decades later, the technology has matured and is being used to restore historical objects, such as a badly deteriorated owl sculpture perched on the northeast corner of the East Block that White worked with CIMS to digitize and reproduce.

And it is being used to help create new ornamentation, “which seems to have been forgotten for decades,” says White, who is also working with CIMS on a collection of 10 decorative maple leaves that will be milled into wooden panels, cast in glass and carved out of stone for the Government Conference Centre.

“PSPC sees great future potential for these robots,” says the department, a collaborator with CIMS since 2008.

“They are examples of how projects within the parliamentary precinct are leveraging innovation and technology.

“Innovative digital fabrication technology has been used in a complementary fashion with old world craftsmanship as a new method of delivering stone carvings and stone repairs required by the rehabilitation projects on Parliament Hill, while continuing to respect the heritage character of these elements.

“All sculptural elements found on the interior and exterior of the buildings are being modelled to create a database of historic elements, which can called upon when repairs are required. In addition, in the future, these 3D models can be shared online to allow interested individuals to view and explore the sculptural artisanship on Canada’s Parliament Buildings.”

A Return to Ornamentation

Stone and metal sculptures are expensive and time-consuming to produce, and aren’t regular features on the modernist buildings — boxy structures with clean, straight lines — that have become the norm in our cities.

By reducing costs and the amount of time required, digitally-assisted fabrication could herald a return to the type of ornamentation that was common when the Parliament Buildings were constructed.

“We’re the only university in Canada with a setup of this kind,” says Hayes, the Architecture PhD candidate helming the robot project, currently focused on the heritage conservation components of the major rehabilitation of Parliament Hill.

“I’m interested in seeing what type of new designs emerge,” says David Edgar of RJW Gem Campbell Stonemasons, the head conservator and foreman for the company’s carving work on the West Block restoration project and an independent consultant who has worked with CIMS.

Edgar, who came to Canada from the United Kingdom to work on Parliament Hill and has been involved since the first scaffolds went up, says this technology could be perceived as a threat to traditional stone carving. But he prefers to see this shift as a new set of tools that could help revitalize the relationship between his craft and modern architecture.

“It’s not as straightforward as you might think — you don’t just scan an object and hit ‘go’ on the robot,” says Edgar.

“Maybe carvers are going to move into more of a design role, instead of hitting stone. I don’t think I’m going to make myself redundant and I’m interested in learning more about my craft and being part of its evolution.”

“Automation significantly altered the stone industry a long time ago,” adds Hayes. “We’re exploring ways for digital fabrication to work in conjunction with skilled craftspeople.”

“A craftsperson with skills in stonecutting, woodcarving or metallurgy knows the material qualities of the thing that is to be fabricated,” says CIMS Director Stephen Fai, Hayes’s PhD supervisor. “Material and form are related — but not the same. This knowledge of material informs the imagination of the craftsperson in determining what is possible.

“Can the stone be cut deeply here? Will the grain of the wood allow this detail? Michelangelo is famously credited with saying that the form of the sculpture is already in the stone. The imagination of the craftsperson is what lifts us above the tedium of mindless replicas.

“That said, we need to remember that digital fabrication also requires craft. If accuracy and precision are important — digital capture, digital modelling and translation for fabrication are all exacting tasks that require very specific knowledge and skill sets. To bring heritage and the digital together requires two highly refined sets of skills — two crafts.”

Heritage Conservation through Digital and Traditional Means

Holding a control panel that looks like a souped-up tablet computer, Hayes demonstrates a tool change for the KR 360. The robot gracefully swings around and the drill bit-like attachment at its tip is released and another is secured in its place.

The KR 360, typically used in auto plants and similar manufacturing industries, can rotate 360 degrees, as can the work table where objects that it alters are placed. The arm part has six different axes of movement.

“That’s six degrees of freedom,” says Hayes, who has started an architecture firm with CIMS alumni Darcy Charlton and Ryan Odell, “but also six degrees of complexity.”

After a couple months of calibration work, there is still much to learn about the operation of the machines, although already been used for prototyping with high-density foam. Diamond-covered tooling that will enable it to cut stone has been ordered and is on the way from Italy.

Moving a few feet away to the KR 6, which is enclosed in a Plexiglas case, Hayes places a foam block beneath the milling tool and begins a pre-programmed sequence.

Starting at the top, the robot begins to cut contours out of the foam. The end result will be an aesthetically pleasing abstract decorative ornament — and it will be finished in less than three hours, a project that would take a human craftsperson two or three days.

“It’s relatively rare to be able to do this kind of research as part of an architecture PhD,” says Hayes.

“And our work is just getting started. There’s so much research potential.”

Fai considers the use of digitally assisted fabrication on heritage conservation and rehabilitation projects a logical unfolding.

“Digitization using photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning is well established in the recording of objects, buildings and landscapes that have heritage value,” he says. “This metric information can be translated into very accurate drawings or digital models that can serve as a record or as the basis for conservation or rehabilitation initiatives.

“Over the past decade, the computer hardware and software needed to do this has become increasingly fast and affordable. It is a logical next step to use this same information to assist in fabrication.”

Thursday, June 1, 2017 in Architecture, Research, Technology

Share: Twitter, Facebook