Photos courtesy of Keith Seifert

By Dan Rubinstein

When Keith Seifert walks into a house, he has a hard time stopping himself from looking — and sniffing — around for interesting fungi.

“If there’s mould in a building, the first thing anybody is going to notice is the smell,” says Seifert, a recently retired Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada mycologist and adjunct research professor at Carleton University.

“That’s a good indicator, and your natural reaction is, ‘Oh, this isn’t a good place to be.'”

Mould is a type of fungus, and fungi — a kingdom of about 144,000 known species that also includes mushrooms, mildews and yeasts — are the focus not only of Seifert’s professional and personal curiosity but also his 2022 popular science book, The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi.

Mould is a type of fungus, and fungi — a kingdom of about 144,000 known species that also includes mushrooms, mildews and yeasts — are the focus not only of Seifert’s professional and personal curiosity but also his 2022 popular science book, The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi.

In the book, he introduces readers to the many realms in which we knowingly and unknowingly interact with fungi, from forests and food to our bodies and built environments. And even though Seifert looks at the latter through an ecological lens, not a health perspective, it’s clear from his writing and research that greater awareness about the presence of mould and other fungi in our homes is an important step toward safer buildings.

The average North American house contains the DNA of about 2,000 fungi species, a fair number of which were discovered by Seifert. Approximately 100 of these dominate on damp or wet surfaces. You see them on walls that are wet from leaks or condensation, in the grout around bathroom sinks, in plants, dust and the dishwasher.

Health problems occur when there is visible mould and dampness, which increases the number of spores and fungal fragments in the air, impacting the respiratory systems of all occupants, including people who are allergic to mould and especially children.

“As long as we live in homes and spend time indoors,” Seifert writes, “we will interact daily with the microbial world.”

The Risks of Reduced Ventilation

The shift that exacerbated this situation began in the mid-1970s, when the first energy crisis and high oil prices changed how houses and other buildings are constructed in Canada.

“To reduce heating costs, we increased insulation and reduced ventilation,” Seifert explains.

“The result was buildings with increased humidity and warmer air, both developments that made fungi feel more welcome.”

Although humans evolved with microorganisms and a healthy immune system can cope with routine exposures, Seifert suggests a few remedies, such as periodically wiping the gaskets of appliances with soapy water or rubbing alcohol, replacing carpets with tile or wood flooring, vacuuming regularly and installing a furnace fan with an effective high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter.

He also recommends cleaning small mould colonies on walls or ceilings with appropriate solutions — not bleach — while wearing personal protective equipment, as well as hiring a qualified remediation expert for larger outbreaks. Health Canada has good guidance on how individuals should respond.

Fungi: The Connective Tissue of Life

One of Seifert’s long-time collaborators, Carleton chemistry Professor J. David Miller, is an internationally renowned expert on indoor mould, among other subjects related to toxins and allergens.

Miller helped to draft the current Health Canada residential mould guidelines and the guidelines used by indoor air quality investigators in Canada and the U.S., and is contributing to the next iteration of North American bioaerosol guidance, due out in the spring. Much of the basic science that underpins these guidelines comes from Canada, including research at Carleton.

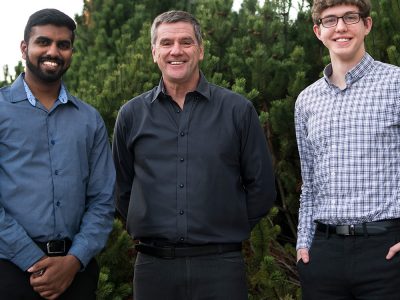

Carleton’s David Miller (left) and Keith Seifert with their former joint postdoc Allison Walker, who is now a fungi researcher at Acadia University

“There has been more public discourse about mould and other fungi lately, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made more people think about proper ventilation,” says Miller. “The first energy crisis that brought vast hardship to people in the United States and Canada, so we overreacted and reduced ventilation rates massively. And then we got a harvest of allergic disease that we still have.

“We generally don’t talk about things like the fungi in our homes or our food,” Miller adds, “and we need people to be engaged if we want to make changes. Books like Keith’s help open a window into this world.”

It’s been said that fungi are the connective tissue of life, allowing trees and other plants to communicate and exchange nutrients through a network of microscopic threads. They constitute about one-quarter of the world’s biomass — “an enormous but largely invisible player in our ecology,” says Miller, “that allow plants to do a lot of the things that they do.”

Beyond houses and other buildings, and the impacts of fungi on human health, Seifert hopes his readers become more attuned to the interconnectedness within and across all natural ecosystems, one of the foundations of a sustainable planet.

“The type of symbiosis that fungi embody is really in the zeitgeist right now,” he says. “This interconnectedness is not a magic bullet solution for anything, but there are benefits to paying attention to our relationship with these microbes.”

Thursday, December 15, 2022 in Biology, Books, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook