By Lisa Gregoire

Marie-Odile Junker, a professor at Carleton University’s School of Linguistics and Language Studies, had a dream years ago where, sad about the disappearance of Indigenous languages worldwide, she finds a teepee occupied by Indigenous Elders who beckon her inside.

When she tells them why she’s sad, a woman gives her a basket. She asks what it’s for and the woman says: “You’ll know when the time comes.”

Two years later, while working with Daisy Moar at Quebec’s Cree School Board on an online language tool, Moar, unprompted, told Junker about a dream where she was picking blueberries, grieving the loss of a mentor and fellow language keeper, and wondering how to continue the work—the blueberries representing their accomplishments thus far.

Prof. Marie-Odile Junker

Moar arrives at a teepee but when she tries to enter, she trips and spills the blueberries, sending them rolling down the hill. An Elder inside the teepee tells her: “You’d better find a basket.”

“I had goosebumps,” said Junker. “Even as I tell it to you again, I have goosebumps. It happens every time.”

Junker explained that in East Cree, if you are describing a dream, verbs take on a specific conjugation—the subjective—to alert the listener that the action has been dreamed. This is not just an interesting lesson in linguistics. It underscores the significance of dreams in Cree culture.

Dreams Lead to Birth of eastcree.org

There was a time when Junker would not have told that story for fear of sounding unprofessional. But having earned a Governor General’s Innovation Award in 2017, authored or co-authored more than 100 articles on Indigenous and other languages, and spent years working with Indigenous women who believe in the power of dreams, she doesn’t worry anymore.

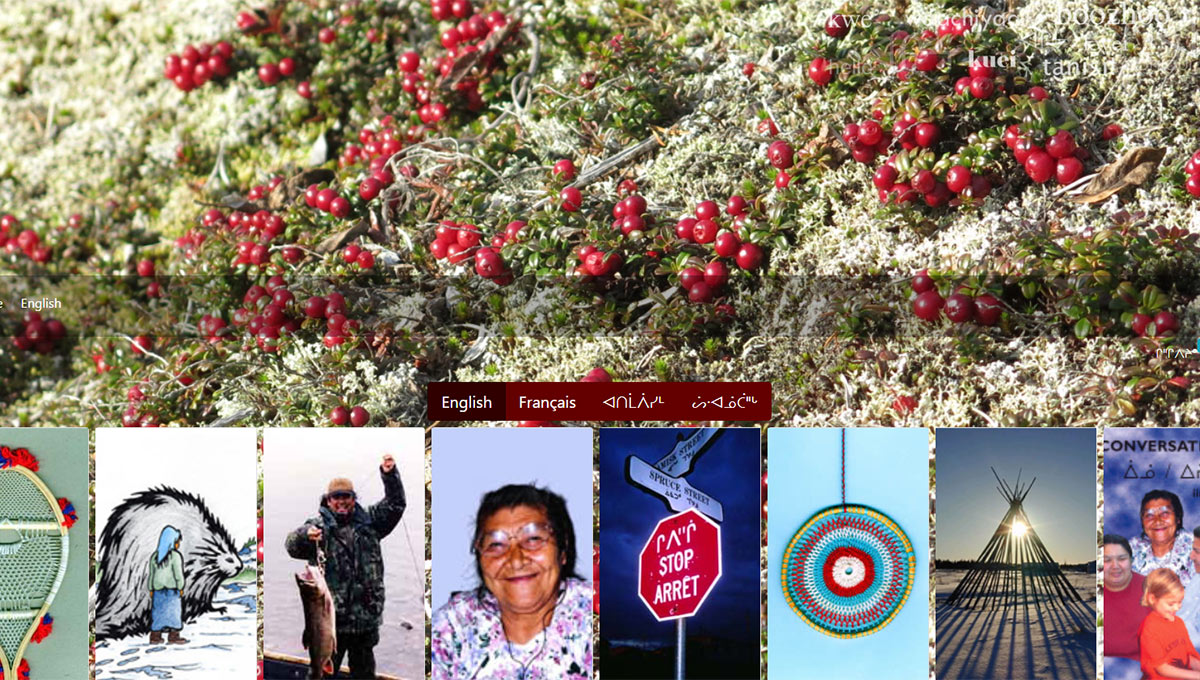

Those dreams, and a lot of effort from a team of Indigenous co-creators, led to the birth of eastcree.org, an Indigenous language website for teachers in remote northern Quebec Cree communities. Built in the early Internet years, eastcree.org was one of the first of its kind in Canada and helped to spawn dozens of similar sites. This month, that unique website turns 20 years old.

Prof. Marie-Odile Junker and His Excellency the Right Honourable David Johnston, C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.D., former Governor General of Canada

But this is not a story about the past. Even though eastcree.org was built with rudimentary, time-consuming coding technology, it is more relevant and useful today than ever.

When COVID-19 closed schools across Canada in March, the Cree School Board turned to full online learning, incorporating resources from eastcree.org into the curriculum and adapting other materials in ways inspired by that unique site.

“It’s not just rewarding for me, it warms my heart,” Junker said. “I never thought this little site would become this. I was just playing in 2000. I was walking around with a question: could this be useful?”

The answer was yes.

One of the people who worked on the site with Junker is great-great-grandmother Luci Bobbish-Salt. Now 73, she was a teacher in Chisasibi and later a language consultant for the school board who helped to create Cree books for children. But eastcree.org, has a unique advantage over books, she says: sound.

“Whenever people say they are going to teach people to read and write the language, that’s fine and dandy, but you have to hear it first,” Bobbish-Salt said from Chisasibi.

Language is the means by which people describe their world, their place in it and the relationships they have there. In East Cree, for example, they don’t use “baby talk” with infants, Bobbish-Salt says. Legends are told and children might not get everything at first, but after each telling, they understand more as they observe the world and begin to experience it. Language is not part of a person’s culture, she says. It is culture.

“Within language, there are so many things. There are values in language. Many different things that are hard to explain . . . things you can’t translate.

“Our culture is an oral tradition. We never wrote down anything. And to this day, we have those stories. Technology had a lot to do with it, people recording things, and I know some native groups in Canada and the U.S., people lost their language,” Bobbish-Salt said.

“But we are very lucky. I give a lot of credit to the people who started working with our language, like Marguerite [MacKenzie] and Marie-Odile. If they hadn’t done this, a lot of it would be lost today.”

Online Language Sites Take Hold

In the two decades that followed the launch of eastcree.org, many other Indigenous groups—mostly in the Algonquian language family, but some not—asked how they could create similar online sites, dictionaries and interactive atlases to preserve their languages and dialects.

But before diving in, Junker used an innovative, five-year grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council to explore how best to incorporate technology into the field of linguistics and how to properly include the participation of Indigenous collaborators.

That research fundamentally transformed her work going forward. And the timing was perfect.

A screenshot of the eastcree website.

The Internet was emerging as a powerful technology and given how Indigenous peoples had suffered abuse and neglect in Canada, Junker felt compelled, as a linguist with knowledge of computers, to partner with Indigenous groups and help them transfer their words, stories, ideas and knowledge to modern platforms.

“If the technology available for communication does not support your language, then either you will not live in your century, or you will have to let go of your language,” she said.

“It’s a question of equity, of linguistic diversity, of letting people speak with their voice,” Junker said.

Language and healing had always been interesting to me long before anybody spoke about truth and reconciliation.”

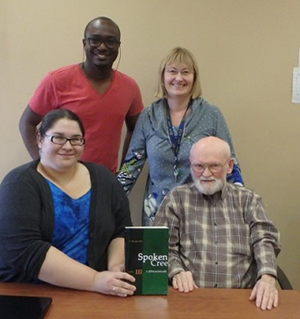

Caitlyn Martinuzzi, Delasie Torkornoo, Marie-Odile Junker, and Doug Ellis

Junker credits success of eastcree.org to a large, passionate team that has included, over the years, dozens of Indigenous co-creators—mostly female language keepers such as Moar, Bobbish-Salt, Louise Blacksmith and Linda Visitor—along with senior linguist Marguerite MacKenzie and expert programmers such as Ghanaian-born Carleton alumnus Delasie Torkornoo, “the invisible man behind the woman,” with whom Junker has worked for 13 years.

She describes herself as a kind of midwife who helps groups give birth to their own language projects. A scroll through her website reveals 19 online Indigenous language resources she’s had a hand in delivering, including the prolific Algonquian Linguistic Atlas, an interactive, cross-Canada tool where you can read and hear phrases spoken in 20 languages.

So while eastcree.org celebrates its 20th birthday, this story is just beginning. Her younger siblings are legion and the family is still growing.

Monday, June 15, 2020 in Indigenous, Linguistics

Share: Twitter, Facebook