By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Mike Pinder

Some strange organisms are growing at the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG). There are fungi in plain sight.

No, there’s no humidity problem at the gallery. The live specimens of mushroom mycelium are part of “La chambre des cultures, foraging in time and space,” a collaboration between Gatineau artist Annie Thibault and Carleton Biology Prof. Myron Smith.

The exhibition, which includes photographs and drawings, was inspired by Thibault’s research and experimentation as an artist-in-residence in the university’s Biology Department. It’s one of five new shows that the gallery opened in September, including “She Wants an Output,” a look at the history of Ottawa’s punk music scene that’s on display inside the main entrance of the MacOdrum Library.

As CUAG celebrates its 25th birthday this fall, this fusion of art and science — a pilot project complemented by “HERbarium,” a student-curated exhibition that focuses on Canada’s largely unknown pioneering female naturalists — embodies a longstanding commitment to creative expression that engages the Carleton community and connects it to the outside world in bold and imaginative ways.

“This fall’s group of exhibitions exemplifies our key interests and priorities,” says CUAG Director Sandra Dyck, who officially opened the suite of new exhibitions at a well-attended anniversary party on Sept. 11, “and does so with energy and excitement.”

Foraging in Time and Space

In “La chambre des cultures, foraging in time and space,” Thibault — who studied science at university before turning to art, and has worked with plankton, mold and microscopic algae in the past — cultivates and documents the underground mycelium networks that allow mushrooms to share information and nutrients.

“She works instinctively with fungi as artistic material,” says the exhibition’s curator, Heather Anderson, “exploring and revealing what are often invisible aspects of our world.”

The adjacent “HERbarium” exhibition — presented in the Carleton Curatorial Laboratory by six students who participated last winter in the “Representations of Women’s Scientific Contributions” seminar offered by Women’s and Gender Studies Prof. Cindy Stelmackowich — presents examples of the scientific work of women such as Ottawa mycologists Irene Mounce and Mildred Nobles.

Attendees take in “La chambre des cultures, foraging in time and space” by Gatineau artist Annie Thibault and Carleton Biology Prof. Myron Smith.

“Because of the accessible nature of plants close to home, and the national pursuit and desire to see, describe and classify flora and fauna species that were distinct from Europe within what is now Canada, botany became the best-known science formally practised by Canadian women,” the student curatorial team write in the exhibition’s introductory panel. The exhibition also looks at the continuing need to encourage women to pursue careers in science, where they face ongoing discrimination on the basis of gender, race, sexuality, disability and class.

This subject is significant, says Dyck. So is the fact that it was curated by a diverse group of students, working collaboratively and across disciplines — a testament to the gallery’s mandate to help develop the next generation of curators, to open up interdisciplinary conversations, and to demonstrate the vital role that art plays in helping us interpret and make sense of our rapidly evolving world.

“Our exhibition program is carefully planned, over the long term,” says Dyck, who had just started her master’s in Art History when the gallery opened in 1992, and has been at the helm for the last five years.

“We want to be timely and relevant to contemporary society. We want to inform and inspire important conversations, and to engage with the world in real and substantive ways.”

A Distinct Role in the Cultural Landscape

University art galleries play a distinct role in the cultural landscape. Unlike national, regional and municipal institutions, they serve and reflect a specific community. But because of the nature of art — a bridge between the personal and the universal — galleries such as CUAG provide opportunities for universities to deepen their relationships with diverse communities beyond the campus.

Yale University’s art gallery, which opened in 1832, was the first university gallery in North America. The Owens Art Gallery, at Mount Allison University in Sackville, N.B., was the first in Canada, opening in 1895. Today, there are more than 40 in Canada. CUAG — located in its original 4,830 square feet of exhibition space in the St. Patrick’s Building near the northern end of campus — is one of a handful at a university without an art studio program.

As the CUAG website recounts, the prospect of a campus gallery was first discussed in 1970, just four years after Carleton’s Art History Department was established. There was widespread support for the idea, amid growing interest in the arts in Canada, but the project stalled in 1972 when the Ontario government froze university funding.

A 2016 performance by artist Carol Sawyer featuring a harpsichord owned by Ottawa art collector Frances Barwick, who helped bring the Carleton University Art Gallery to life in 1992. Photo Credit: Justin Wonnacott

A “transformative bequest” from Ottawa’s Frances and Jack Barwick, who donated 57 works from their collection of Canadian art as well as a generous financial gift, ultimately led to CUAG opening its doors on Sept. 23, 1992. The Barwicks’ contribution was augmented by Carleton’s successful community-wide fundraising campaign, and by an expanding collection of more than 80 other artworks that the university had started collecting in the mid-1960s.

This start was aligned with Carleton’s origins as an egalitarian, community-focused university, says Michael Bell, who was hired as CUAG’s first director and had previously worked as the assistant director for Public Programs at the National Gallery of Canada and as director and CEO of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, among other positions.

“Starting up something from scratch was a totally different experience,” says Bell, comparing his role at CUAG to his earlier posts. “Especially because we had no operating budget.”

Carleton’s dean of Arts at the time, Janice Yalden, came up with a creative way to fund the gallery. She designated it an “art laboratory,” which gave it access to research funds, and then encouraged Bell to sell his case to Carleton’s other deans. They all agreed to contribute to an operating budget to support CUAG in its formative years.

“It was such a beautiful gallery space to work with,” says Bell. “It has presence, but does not fight with the content. The space was always sympathetic to the art, whether it was Mexican ceramics or contemporary art. It all just fit. In my humble option, we had the finest university gallery space in the country for its size.”

A Focus on First Nations, Métis and Inuit artists

Since its birth 25 years ago, CUAG has maintained a focus on the work of contemporary First Nations, Métis and Inuit artists. One of Bell’s fondest memories of his 11 years as director is of “Kanata: Robert Houle’s Histories,” a 1993 exhibition featuring work by the internationally acclaimed Saulteaux artist.

The focal point of the gallery’s first solo exhibition of a contemporary artist was Houle’s monumental painting “Kanata” — a reframing of Benjamin West’s iconic “The Death of General Wolfe,” in which the clothing of a Delaware warrior is vividly coloured while the rest of the dramatic scene is pale. It was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada immediately after the CUAG exhibition.

Houle’s work will return to CUAG in January 2018 in “Pahgedenaun,” an exhibition — curated by Dyck — of works in which he addresses the traumas he experienced as a child while attending residential school in his home community of Sandy Bay First Nation on the western shore of Lake Manitoba.

These two shows bookend a long list of exhibitions of the work of Indigenous contemporary artists, including the nationally-touring exhibition “Meryl McMaster: Confluence,” and this fall’s “Always Vessels,” curated by Carleton PhD student Alexandra Kahsenni:io Nahwegahbow, featuring nine contemporary Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee artists whose media and subjects range widely, from glass beads to photography, and from language to land.

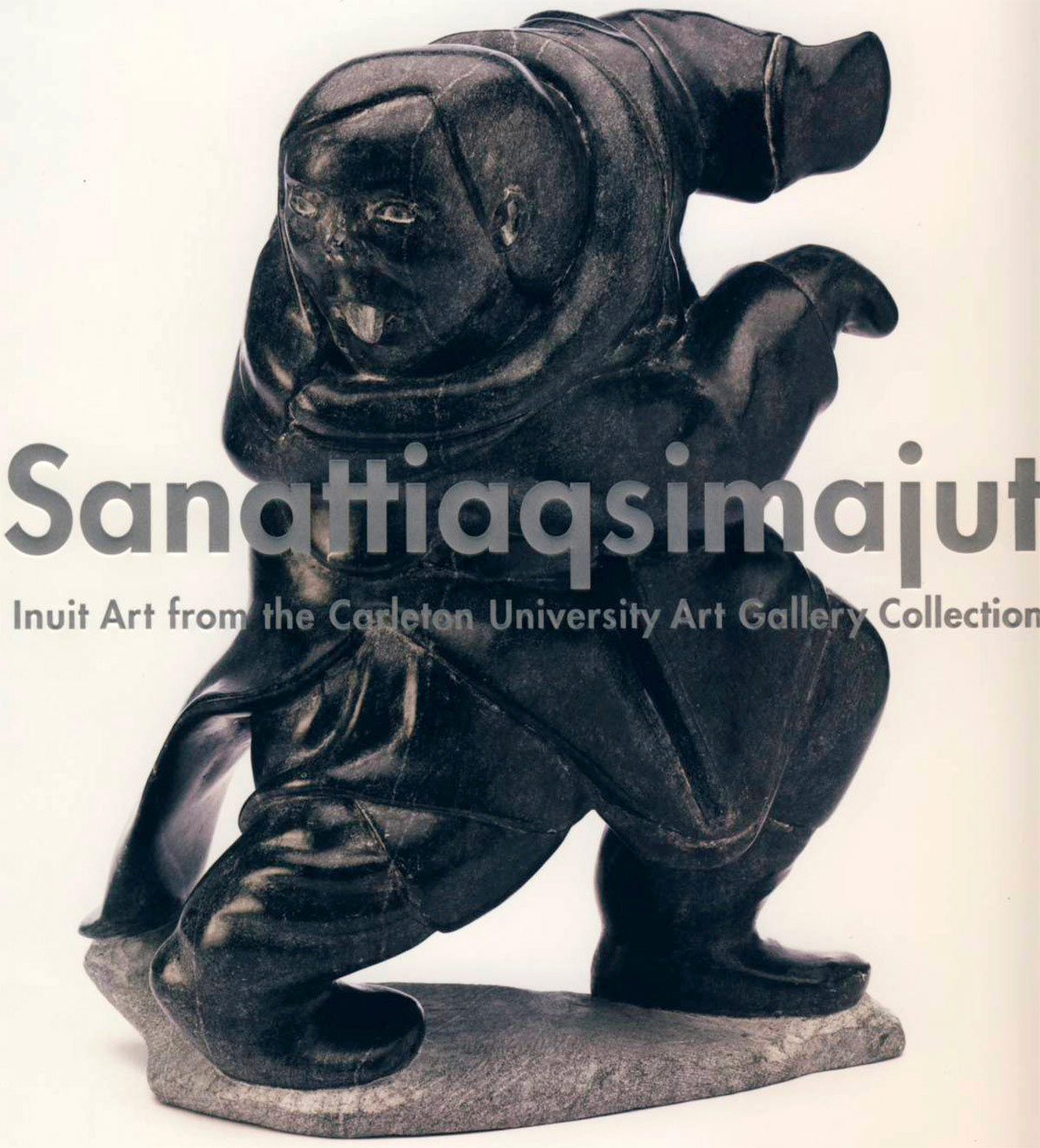

Much of CUAG’s programming over the years has featured the work of Inuit artists, reflecting the gallery’s extensive collection — the focus of one of its first major gifts, from Priscilla Tyler and Maree Broks, an act that encouraged other collectors to follow.

This specialty is showcased in the stunning 2009 book Sanattiaqsimajut — Inuktitut for “these things that are finely made” — which won first prize for exhibition catalogue design in that year’s American Association of Museum Publications Design Competition (in the category for institutions with budgets less than $750,000).

The full-colour, richly-illustrated hardcover documents the highlights of the gallery’s rich collection of Inuit art, and speaks to a successful publishing program, one of the many forms of outreach at the gallery. Many of the students who had formerly curated exhibitions of Inuit art over the years at CUAG contributed essays to the catalogue.

Emphasizing Art-Based Public Programs

Beyond its exhibitions and catalogues, CUAG has a strong emphasis on art-based public programs. These initiatives take many forms and are offered under the umbrella of CUAG Connects, an education program run by Fiona Wright, the gallery’s student and public programs co-ordinator.

In 2014, the wildly successful Art + Sports Camps were launched, a collaboration between CUAG and Carleton Athletics that has inspired spin-off summer camps run by the English and Earth Sciences departments.

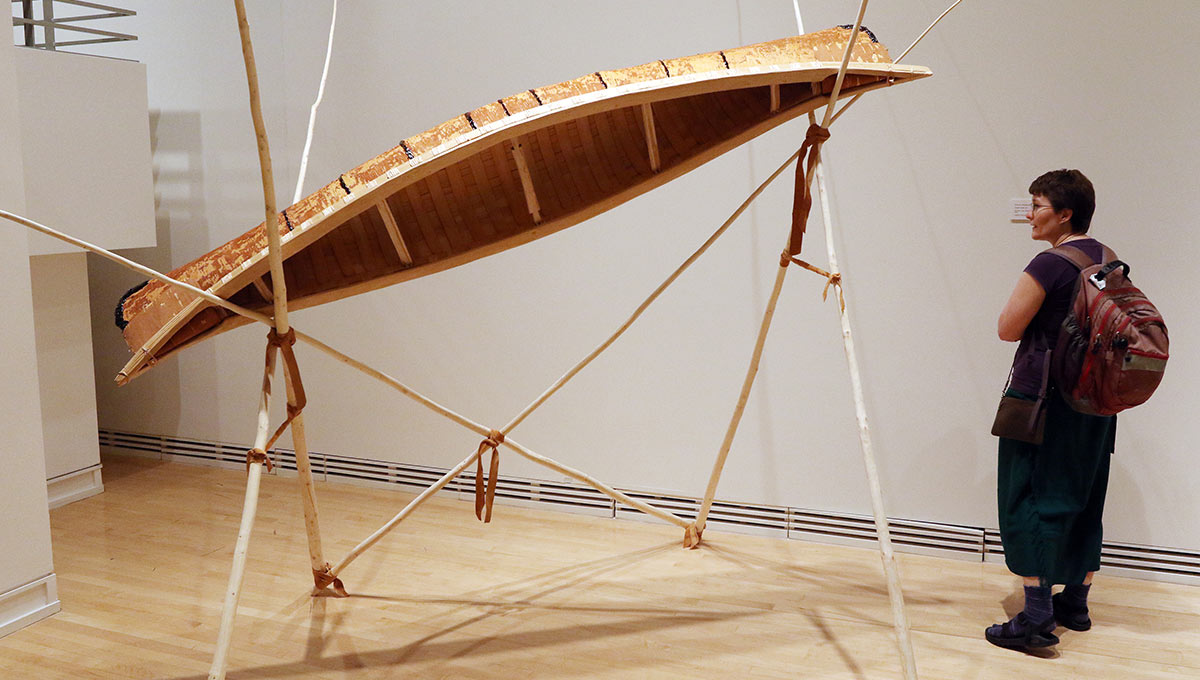

There are also collaborative co-learning projects, such as the recently completed birchbark canoe, a partnership between CUAG and Carleton’s Centre for Indigenous Initiatives that saw students build an eight-foot canoe that’s now permanently on display just inside the main entrance of the MacOdrum Library. “I can’t even put into words how special that project was,” says Dyck.

A wigwàs chinam (birchbark canoe) made by Pinock Smith, included in the “Always Vessels” exhibition.

Moreover, CUAG is behind a series of pop-up performances on campus throughout 2017 by Music Prof. Jesse Stewart, and frequently invites guest curators to organize exhibitions — in addition to the 30 per cent that are curated by students — to ensure that a multitude of perspectives are represented in its programming.

As part of the “She Wants an Output” off-site exhibition at the library, curator Michael Davidge organized at punk concert at Oliver’s Pub on Oct. 6 in conjunction with the show — another example of how CUAG is engaging the campus, not only in the gallery itself.

Now that CUAG is generously supported with operating funding from the Ontario Arts Council, Canada Council for the Arts and Carleton, and has four and a half full-time staff positions (compared to one and a half when it opened), Dyck and her colleagues can look farther ahead and find new ways to connect the gallery to the outside world.

As Bell says: “The gallery is basically a window that works both ways. It is and always has been a significant contributor to the local cultural scene, and also serves Carleton as a stimulating environment for aesthetic and intellectual innovation.”

Thursday, November 16, 2017 in Art Gallery, Arts and Social Sciences

Share: Twitter, Facebook