By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

Despite the chill in relations between Russia and NATO members like Canada in recent years, a mutual interest in the Arctic represents an opportunity to collaborate – not only on northern issues, but also to move toward improved bilateral Canada-Russia co-operation more broadly.

Diplomats, researchers, policy-makers, government officials, businesspeople and Indigenous leaders packed a hall at Carleton University on Nov. 24 for a day-long conference focused on the need for dialogue about the Arctic between Canada and Russia.

Alexander Darchiev, Russia’s ambassador to Canada

“This event shows the way our countries co-operate on critically important issues,” Alexander Darchiev, Russia’s ambassador to Canada, said in his opening remarks, acknowledging what he called “the delicate context” of international diplomacy.

“The general goal today is to show the full potential of the Arctic as a territory of dialogue and peace,” said Darchiev. “People who have lived for generations in the North know there is no alternative to co-operation. For those who live on their own land, the Arctic is not the far end of the Earth, it’s not a frontier to get whatever resources you can and then leave — it’s home, a place we need to work together to improve.”

The conference, on the heels of the first Swiss-Canadian Polar Research Symposium at Carleton earlier in the week, was organized by the university’s Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (EURUS) and Centre for Governance and Public Management (CGPM), with support from the Faculty of Public Affairs, in partnership with Global Affairs Canada and the Russian embassy. Both events showcased Carleton’s leadership in northern research, from physical and social sciences to the policy front.

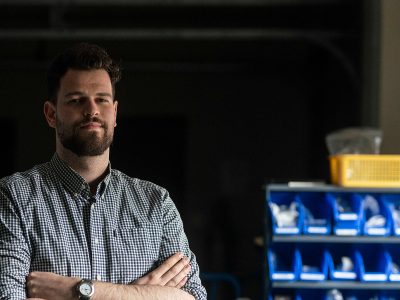

Carleton political science Prof. Piotr Dutkiewicz, co-director<br /> of the university’s Centre for Governance and Public Management

On Nov. 24, three key themes were on the agenda: the environment and sustainable development, Indigenous peoples and sustainability, and the future of Canada-Russia co-operation in the Arctic. The gathering was also infused by the recognition that, considering the geopolitical tension wrought by conflict in the Ukraine and Syria, any civil and productive conversation between Russia and Canada is a step in the right direction.

“The idea here is simple: let’s talk to each other,” said Carleton Political Science Prof. Piotr Dutkiewicz, co-director of the CGPM and one of the conference’s main organizers. “The question is: where do we start?

“We know what kinds of differences we have. It’s time to engage.”

There are two topics, anti-terrorism and the Arctic, that Canada and Russia are “ready to talk about at the highest level,” said Dutkiewicz. “The Arctic is an indirect way to help us build ties that will be helpful in other areas.

“This started as a conference between academics and community leaders, and it has become something much larger than we thought it would be.”

A History of

Canada-Russia Exchanges

Even during the Cold War, Canada and Russia responded to the need to work together in the North through efforts such as the 1984 Canada-USSR Arctic Science Exchange Program.

Power competition between Russia and the West, said University of Waterloo historian Whitney Lackenbauer, does not revolve around Arctic resource or boundary disputes.

Michael Byers, a Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia, said the changing dynamic between Russia and the United States has provided an opening for Canada to step up from the sidelines.

“The world is too interdependent to close off a big country like Russia and say: ‘We won’t deal with you,’” said Byers. Regardless of what’s happening in the Ukraine or Syria, “it doesn’t mean we can’t co-operate on the environment, search and rescue, and other matters in the Arctic. It’s a really important time for lines of communication to be open, and to focus on immediate Arctic needs.”

Alison LeClaire, a director general at Global Affairs Canada

Collectively, Canada and Russia account for 75 per cent of Arctic land, noted Alison LeClaire, a director general at Global Affairs Canada and the department’s senior Arctic official. The nations share similar challenges: climate change, the remoteness of the region and the health of Indigenous communities. Phenomena such as permafrost degradation and melting sea ice have a significant impact on infrastructure and food security in both countries, as do new developments, including the increase in shipping and tourism.

“How we address these issues will help northern communities adapt to the new climate reality,” said LeClaire.

Opening a dialogue may be the overriding purpose of the conference, she added, “but there are also concrete avenues for bilateral action.”

In the first panel, on the environment and sustainable development, a succession of speakers introduced specific areas of common interest. Carleton professors Francis Abele and Chris Burn talked about Indigenous governance and the impact of melting permafrost on road maintenance and construction, respectively. Stephen Mooney, director of cold climate innovation at Yukon College, concentrated on opportunities for renewable energy in the North, while Rita Cerutti of Environment and Climate Change Canada, co-chair of the international Climate and Clean Air Coalition, raised the concerns around short-lived climate pollutants.

Indigenous Issues

and Arctic Sustainability

A second panel looked at the diverse range of connections between Indigenous peoples and Arctic sustainability.

Anna Otke, a senator from Russia’s autonomous Chukotka region, provided a status report on conditions experienced by the area’s smaller Indigenous groups. At the other end of the spectrum, Inuit art consultant Kyra Vladykov Fisher, who has lived in Nunavut for years, looked at how cultural identity is expressed through art.

“The voice of Indigenous people must take a central role in these types of discussions,” said Nancy Karetak-Lindell, president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council Canada. “We were here long before political international borders were in place. Our use and occupancy of the land allowed countries to lay claim to these vast and important territories.

Vladimir Barbin, the senior Arctic official at Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs

“Because Canada and Russia share much of the Arctic, it is our responsibility to work together to improve social conditions,” she continued.

“We must move toward decision making that envisions a healthy future for our families and our collective communities amid all of the attention that the Arctic is receiving.”

Russia’s deputy trade commissioner to Canada, Valerii Maximov, talked about the importance of investing in education in Indigenous communities in his country’s northern regions — a priority in Canada as well.

Maximov also highlighted success stories, such as a wind energy project and bison reintroduction program in the Russian Arctic, positive examples of sustainability and wildlife management efforts that show the potential for progress.

André Plourde, Dean of Carleton’s Faculty of Public Affairs

In a similar vein, research and strategies that make mining in the Arctic more environmentally friendly can produce best practices that boost sustainability in every nation with a footprint in the North.

Government, academic and Indigenous leaders from Canada and Russia must keep talking about all of these environmental, economic and social issues, Karetak-Lindell urged, and use technology to bring together people who are geographically distant. Political and financial support is essential to facilitate this communication.

“We are defined by what we do during challenging times,” she said. “How will we address the challenges we face and create new opportunities? Together we are stronger and can meet the challenge of change.”

Friday, November 25, 2016 in Environment and Sustainability, Indigenous, International

Share: Twitter, Facebook