By Joseph Mathieu

Photos by Joerg Emes and Josh Hotz

Halfway through the 2020 winter term, Carleton University’s CTV Chair in Digital Science Journalism, Sarah Everts, began discussing COVID-19 in her environmental reporting class.

If the coronavirus came to Canada, how should reporters cover it? How would its spread impact efforts to curb climate change? What were the best ways to report on confirmed cases when those numbers represented real lives and deaths?

“When I saw COVID-19 become the story of the year — perhaps the decade — I definitely wished that I was in the thick of reporting again,” says Everts, who left full-time reporting to join Carleton’s journalism faculty in January 2019.

Prof. Sarah Everts

As the science journalism chair, she researches issues in her field and helps train the next generation. She walks students through the many steps a science journalist must take to verify key information, especially during times of crisis.

Everts says that reporters don’t need to be medical experts to cover COVID-19, but they must be able to distinguish legitimate science from quackery.

Along with colleagues in the School of Journalism and Communication, she embarked on a research project to examine how journalism is being consumed by audiences across Canada during the pandemic, with a particular interest in how Canadian audiences are getting COVID-19 information and misinformation.

“Science journalism isn’t just about reporting on new research discoveries,” says Everts. “It’s about holding scientists, science policy-makers and others in the scientific enterprise accountable. But it’s also important to hold the media accountable.”

Reducing Stigma in the Media

On that front, Everts is interested in how the media perpetuates stigma, particularly as it relates to health issues.

In her opinion, many news organizations have improved their coverage of mental health issues so they don’t perpetuate stigma about depression, anxiety and other conditions. But she says media coverage of drug use and obesity still needs to improve.

“Reducing stigma, for example, is consistently listed as an essential component for fighting the opioid crisis, by both government agencies and organizations that advocate on behalf of people who use drugs.”

Internalizing stigma creates barriers for those seeking help and undermines the road to recovery, she says. According to Everts, far too many media outlets report on the opioid crisis using derogatory language to describe what is a chronic health condition, and far too little media includes the voices of people who use drugs.

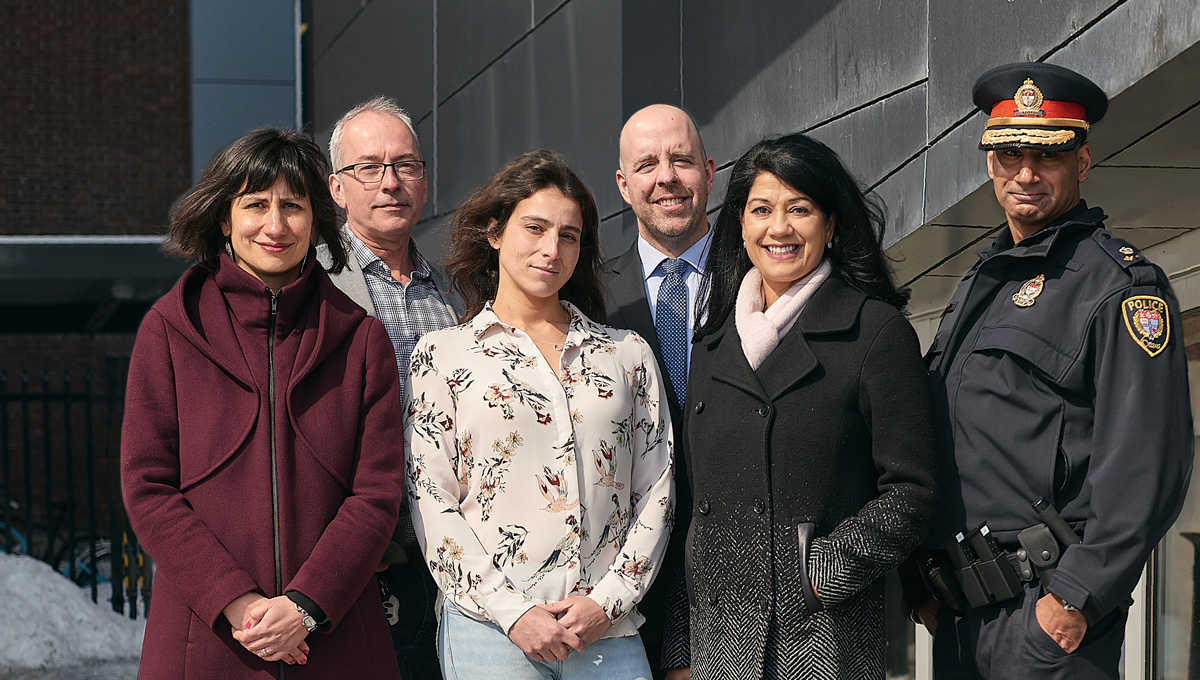

Prof. Sarah Everts stands with participants of a panel discussion on the impacts of stigma and the role of media in shaping perceptions.

Everts grew up surrounded by science: her mother studied genetics, and the kid’s program Wonderstruck with Bob McDonald was her favourite TV show as a child in the late 1980s.

But despite a budding research career, which began with a University of Guelph Bachelor of Science in biophysics and then a master’s in chemistry at the University of British Columbia, Everts decided she couldn’t commit to just one stream of science.

“I really love science but I have a short attention span,” she says. “This is not conducive to being a good scientist because you have to repeat an experiment so many times.”

A Master of Many Trades

After her master’s degree, she wrote proposals, newsletters and annual reports for science funding agencies and travelled between contracts before she sold her first story. She wrote a travel article about Belize for the National Post in 2003.

“This is what I want to do,” she told herself.

After a MJ at Carleton in 2006, Everts went on to write on various subjects, including chemical weapons, the conservation and authentication of art and artefacts, and chemical communication like odors and pheromones. The award-winning science journalist’s work has appeared in Scientific American, New Scientist, Maclean’s, The Globe and Mail and The Economist, among other publications.

Everts is currently writing a book about the science, history and culture of sweat, which began in 2011 when she was a visiting scholar at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia.

The book covers the quest for human pheromones, the history of deodorant, why people sweat in the first place and why so many cultures have taboos about perspiration — one of the things, like big brains and relatively hairless bodies, that distinguishes humans as a species.

Friday, July 10, 2020 in Journalism and Communication

Share: Twitter, Facebook