By Daniel McNeil

In 1971, the Yale professor Robin Winks wrote that Black Canadians wanted “nothing more than to be accepted as quiet Canadians.”

In The Blacks in Canada, Winks claimed that Black Canadians were “unlikely to organize militant, noisy, pushy protests.” He considered Daniel Hill, the first full-time director of the Ontario Human Rights Commission in 1962, to be an exemplary model of quiet leadership.

Hill returned the compliment by praising Winks’ history of Blacks in Canada as a powerful tool in his campaigns against serious discrimination in housing, education and employment. Hill’s study of human rights in Canada for the Canadian Labour Congress in 1977 also denounced “aspiring leaders” in militant organizations who did not propose what he considered to be constructive action.

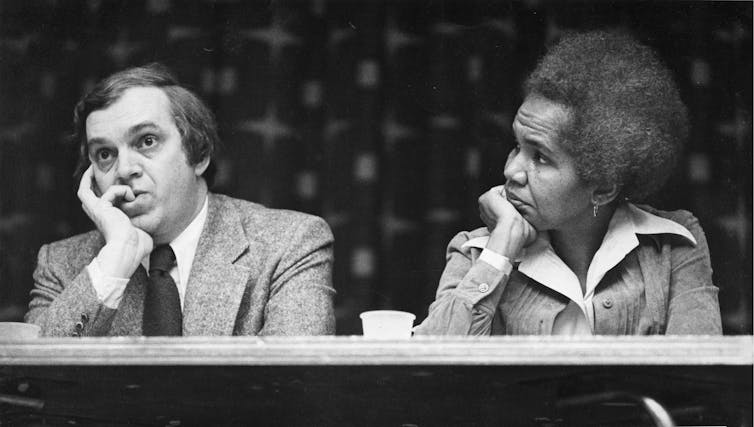

Yet whereas Winks was a rather unabashed elitist who had little time for “simple minds,” Hill translated the work he gleaned from “obscure historical journals” into popular histories. He would work closely with his friend Alan Borovoy, the longtime general counsel for the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, who defined his anti-racist campaigns against “ineffectual intellectuals with no concept of action.”

Hill and Borovoy may be described as Canadian “shy elitists.” They were uncomfortable with anything that they considered too elitist or radical for Canadian tastes. Yet they also encouraged the public to celebrate and defer to prominent, “respectable” figures in elite institutions.

Since we have not ended our dependence on shy elitism, there remains an understandable interest in celebrating Black men and women who have achieved recognition from the Canadian state.

However, we also need to recognize that Black Canadians are not problems when they do not conform to the model of a quiet leader. They are people who confront the problem of shy elitism in Canada.

Consider some of the challenges faced by the politician, social worker, human rights advocate and academic Rosemary Brown.

Introducing Rosemary Brown

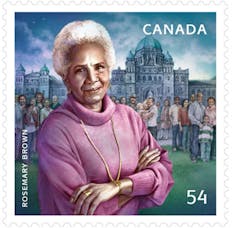

Rosemary Brown moved to Canada in 1951 from Jamaica to study social work at McGill University. She became the first Black woman elected to a provincial legislature in Canada in 1972 and the first Black person to run for leadership of a federal political party in 1975.

Featured in a profile in the Toronto Star on Jan. 9, 1973, Brown was introduced as a “McGill University graduate, wife of Vancouver psychiatrist and mother of two.” Aside from the sexism of highlighting her marital and parental status, such descriptive remarks reminded Canadian readers that Brown was educated at McGill, an institution known for training young people to become the next generation of quiet Canadian leaders.

In other words, Brown was portrayed as a solid, respectable member of the middle class who defied North American stereotypes of Black cultural pathology and single mothers raising children outside of nuclear families.

Brown responded to these media profiles by pointing to her upbringing in Jamaica in the 1930s and ‘40s. Unlike Blacks in Canada in the 1960s and ’70s, she could claim that she grew up in an environment in which the “governor was Black, judges were Black, the police were Black, anyone who was anyone was Black.”

Exoticizing Rosemary Brown

In the British Columbia legislature, politicians like Pat Jordan, the conservative-populist Social Credit Party MLA, asked why Brown did not move back to Jamaica to solve its problems of “slave labour and poverty.”

Media profiles questioned Brown’s socialist credentials by pointing to her comfortable upbringing and privileged status in Jamaica. Stories in The Vancouver Sun highlighted her expensive home in the fashionable Point Grey area and her Parisian wardrobe. Chatelaine magazine depicted Brown as “deliciously minority and yet so chic.”

Brown’s dismissal of these sneers about radical chic did not go unnoticed by Canadian commentators. Journalist Allan Fotheringham identified a certain haughtiness in Brown’s public demeanour. Bob Hunter, the public intellectual, eco-theorist and founder of Greenpeace, said that Brown had to pass through hoops that were understandably frustrating to someone with her intelligence and potential to become Canada’s “Philosopher Queen.”

Domesticating Rosemary Brown

In her autobiography, Brown conceded that she increasingly felt the need to communicate her message in the “safest, most acceptable and bland” terms to the Canadian voter.

This did not mean that she shied away from controversial issues. It did mean, however, that her campaign to become the federal leader of Canada’s left-leaning New Democratic Party would repeat Canadian platitudes. It was claimed, for example, that the candidacy of a Jamaican-born feminist offered voters an opportunity to live up to Canada’s claim to be a multicultural “nation of immigrants.”

Brown also stressed that responsible, quiet human rights organizations had “more lasting impact on the quality of life” of Black Canadians than more prominent or newsworthy radical organizations.

Although she would not win the NDP leadership, Brown would emerge from the contest with a national profile as a dynamic speaker who could convey the realities of racism and sexism in a manner that was palatable to “ordinary, fair-minded Canadians.”

Brown was increasingly portrayed in the media as a responsible Canadian who encouraged minorities and women to achieve major social change by working inside formal institutions.

Unsettling shy elitism

Brown upheld the legacy of Daniel Hill as chief commissioner of the Ontario Human Rights Agency between 1993 and 1996. She also became an Officer in the Order of Canada in 1996 after she lamented the failure of academics and critical theorists to do anything that might appear “commercialized, common or ordinary.”

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose?

To unsettle the system of shy elitism in Canada, we need to contest oversimplified solutions to the so-called problem of Blackness in Canada.

We must also generate critical questions about when and why a Canadian state recognizes Black activists.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Sunday, February 24, 2019 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook