By Lesley Barry

Photos by Chris Roussakis

Floodwaters lapping at front windows, charred buildings in the wake of a wildfire, homes damaged or demolished by heavy winds; the images are by now distressingly familiar. Climate change, the primary disruptor of our times, has introduced a new consideration into housebuilding. How can we start weather-proofing homes to withstand severe unpredictable weather?

“We can improve resilience – the capacity of a house to survive extreme weather events – in how we build our homes and plan our neighbourhoods,” says Gary H. Martin, a postdoctoral fellow at Carleton University’s Sprott School of Business who focused on sustainable urbanism for his PhD.

“For example, houses can be framed and finished in certain ways that help protect them from wind and flooding.”

However, weather-resilient homes remain on the custom-build fringes of the housing sector. Widespread change requires, among various factors, changes to the building code and that, as it turns out, is far from straightforward.

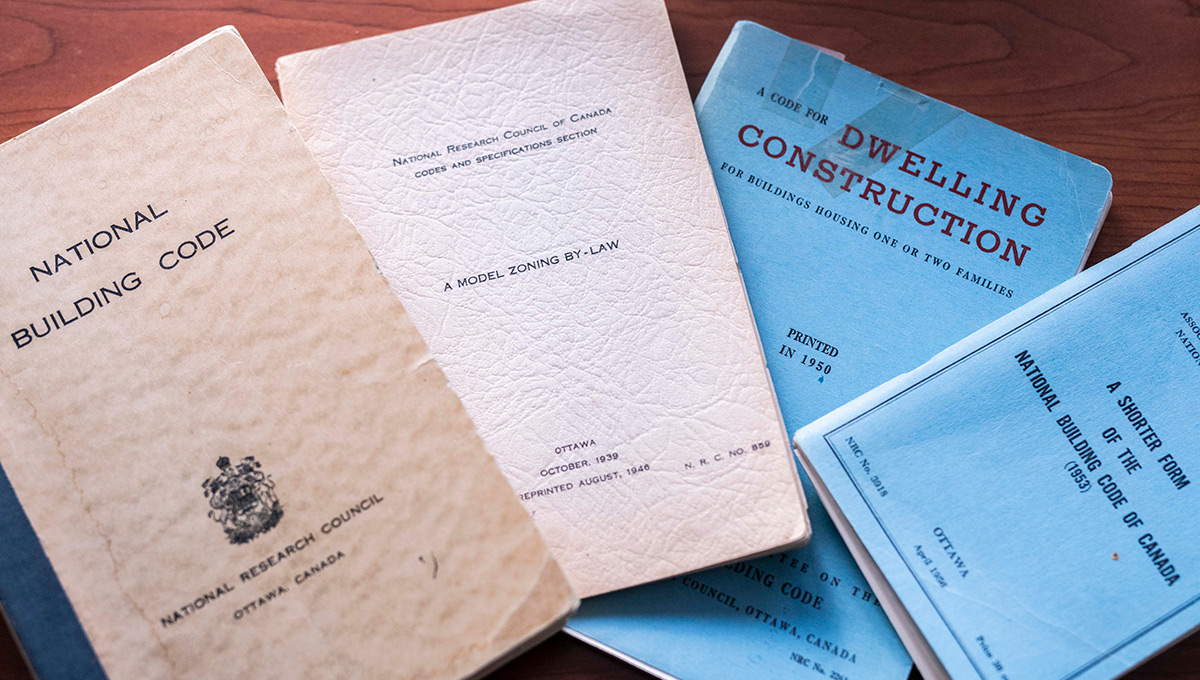

Building codes set out minimum standards of construction for new buildings (and renovations of older buildings) to ensure public health and safety, as well as efficiency relating to energy and water use. The National Building Code of Canada undergoes revision every five years by the National Research Council with input from industry, public stakeholders, and the provinces and territories. Each province and territory then adopts the national code either wholly or in part and passes their jurisdictional code into law.

Martin is examining the revision process for the building code to identify why it’s difficult to integrate the concepts of resilience and adaptation. Arranged through Mitacs, a national research group that uses public funds to support research partnerships between universities and organizations, his study is a one-year collaboration with the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction (ICLR), a non-profit sponsored by the insurance industry.

A Fraught and Arduous Process

So what makes the code change process, in Martin’s words, “fraught and arduous?”

The codes are not only highly technical and complex, they are also politicized: in Ontario, where Martin is focusing most of his attention, the former Kathleen Wynne government added codes around energy efficiency and accessibility according to political priorities.

Moreover, the revision process can be likened to that of Canada’s Food Guide, which has been influenced by industry stakeholders, says Ruth McKay, associate professor of management at Sprott and Martin’s supervisor.

“Interest groups try to change the code for various reasons,” Martin concurs.

“Then other actors will question those changes for various reasons.”

A case in point: hurricane ties. These small pieces of hardware help prevent a roof from lifting during a severe wind by anchoring it to the wall framing more strongly than currently mandated by the code.

Extensive damage after six tornadoes touched down in the Ottawa region in September 2018.

“They cost a dollar or two, but you need a lot of them and they’re time-consuming to install,” says Martin. “The insurance industry considers them inexpensive protection for houses, and ICLR has requested their inclusion in the code twice in the last 10 years, unsuccessfully. The bottom range of their cost is $200 per house, which may not seem like a lot to a consumer, if it’s the difference between your roof staying on or blowing off.” Any home that loses its roof must be demolished and rebuilt.

However, the building industry, which Martin describes as generally conservative and risk-averse, estimates the cost of the ties to be $1,000 or more per house, and some industry players argue the cost is incommensurate with the risk.

“We saw extensive damage after the six tornadoes touched down in the Ottawa region in September 2018, but there is some validity to the argument that tornadoes are too rare to justify this code change across Ontario.”

In contrast, code changes preventing basement flooding have been added to the national and provincial codes: “The risk of flooding is more demonstrable and more expensive than the risk of high wind, and so the proposal is more easily justified.”

Homeowners Must Take an Interest in Weather-Proofing Homes

Where are homeowners in all of this?

Buying a house is a major investment; for many, it’s an equity builder and a retirement fund. Apart from their financial significance, houses are homes, places meant to be private, safe and comfortable.

“To the consumer, it’s a home; to the industry, it’s a house,” says McKay.

“Unfortunately, people aren’t thinking about the house component when they buy a home. They’re not asking, given climate change, will it still be standing in another 20 years?”

The highly technical nature of building codes means that homeowners aren’t part of the revision process. Consumer demand and affordability are important considerations in the decision-making, but these are filtered through stakeholders.

“Talking about the impacts of code changes becomes challenging because we are working through organizations,” McKay reports. “We aren’t talking directly to the consumer. Hurricane straps are available, but they don’t appear in any list of housing features. It’s not just that consumers are ill-informed or uninformed, it’s that the dialogue is missing.”

Nevertheless, in his doctoral research and in this current research, Martin has heard consistent reports of homebuyers’ indifference.

“Builders get very frustrated and discouraged that consumers are more concerned about granite countertops than about protecting their homes from severe weather.”

“We definitely need public education,” suggests McKay, “so that homeowners can become part of the conversation.”

A Cross-Disciplinary Business Angle

McKay brings a cross-disciplinary business angle to the project.

“There is pressure to reduce carbon emissions, which is behind the push for sustainable housing,” she says. “But erratic weather means we also need resilience and adaptation. Whichever path you go down has costs, and the housing sector is starting to open up to that. And code changes have costs, and they need a business case attached to them.

“Then there is the overall cost of these climate events to taxpayers and insurance consumers,” McKay adds.

“It’s huge and it’s increasing.”

For his part, Martin brings unusually deep experience to his research. He talks knowledgeably about hurricane ties because, after decades in the building industry, he’s installed more than a few.

He learned about building by working onsite part- and full-time over the course of an undergraduate and master’s degree, then went into full-time contracting, both solo and with other builders, with a focus on sustainable housing.

But mounting frustration with “a housing industry operating on an outdated production model, oblivious consumers and inadequate regulation” propelled him to a doctorate at Carleton. “My current research continues my attempt to inform efforts to rationalize home construction in dramatically changing environmental conditions.”

Martin and McKay are already looking ahead, applying for federal funding to examine how a community of practice can be created among building code stakeholders to enable information-sharing on achieving resilience and adaptation.

When it comes to researching Canada’s housing sector, Martin appears to be, to his and McKay’s surprise, all on his own.

“The housing market is a major indicator of economic health in Canada, and with its many offshoots, the industry is worth billions of dollars,” Martin says.

“Yet there is very little research in this area. There are studies on housing and on the politics of urban development, but after that, I’ve looked for about 10 years and so far found no academic research in Canada on the industry itself.”

Nevertheless, he is, in the vernacular, more than shovel-ready.

“This is the project of a lifetime for me,” he enthuses. “It’s right up my alley.”

Monday, March 18, 2019 in Research, Sprott School of Business

Share: Twitter, Facebook