By Lesley Barry

Photos by Chris Roussakis

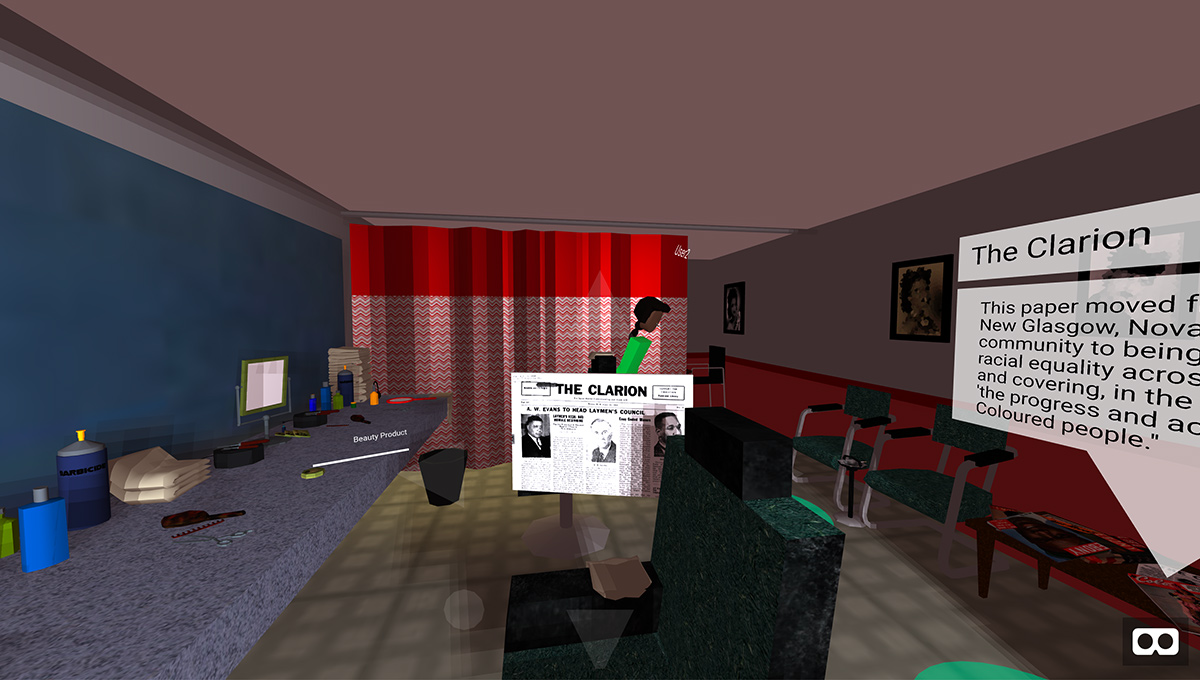

Walking into a peaceful room, you take a seat next to a pile of magazines. Women’s voices, talking and laughing, come from nearby and a breeze ruffles the curtains as a streetcar rumbles past.

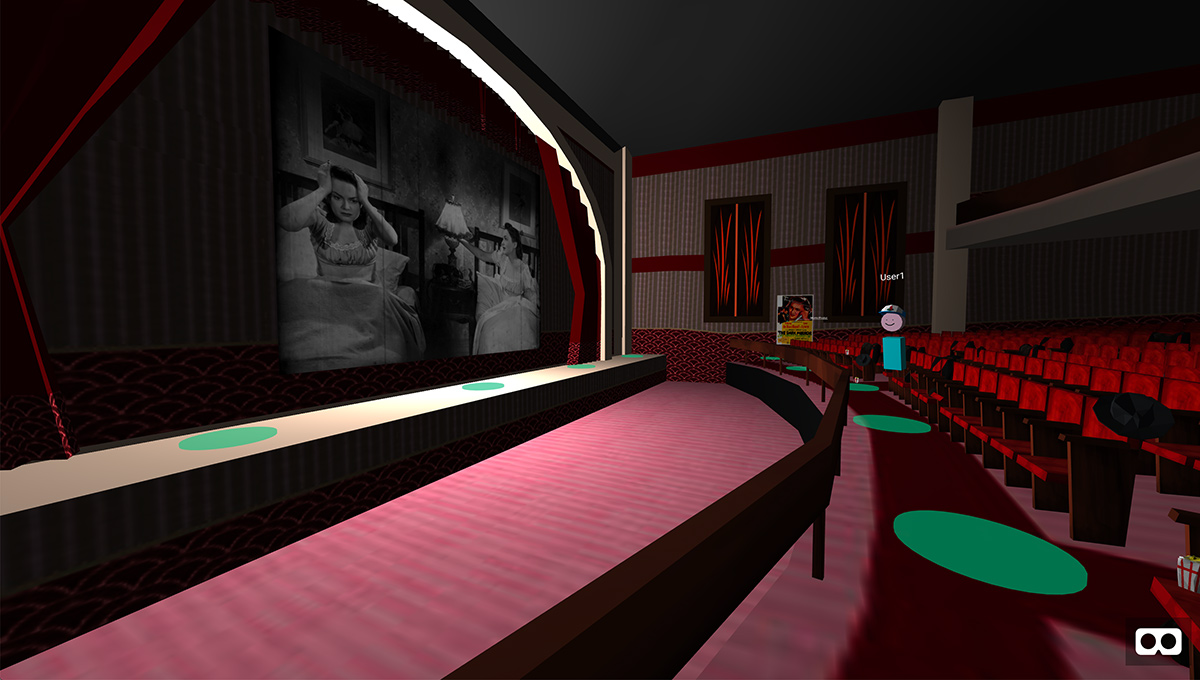

It’s 1946 in Halifax, and you’re in the beauty salon of Viola Desmond, who will soon defy a segregation policy at the Roseland movie theatre and eventually become a civil rights icon and the first Canadian woman to be pictured on our currency.

Welcome to the Circles platform, an innovative educational virtual reality (VR) experience created by Anthony Scavarelli, doctoral student at Carleton’s School of Information Technology.

Anthony Scavarelli

While it’s a truism and challenge of our age that the technology that connects also isolates, Scavarelli has other ideas about that.

“For me, the most important part of technology is the human element,” he says. “I’ve always used computers as a tool for creating experiences that bring people together.”

His approach is unusual – it’s artistic and egalitarian, and driven by a belief that technology can help us connect with each other and with the world around us in lively, creative ways.

Amplifying Learning Effects Through VR

VR in education is his current venue for putting those ideas into action and, for Scavarelli, it begins with VR’s experiential value. “Using our bodies to interact with things or being immersed in a world is known to amplify learning effects.”

Literature reviews of VR use in education, however, reveal a common theme. Usually one person at a time wouldc use the headset and then remove it and talk about their experience.

“Given how much we learn from shared experience, that seemed strange. So I wanted to combine social cognition with the experiential learning VR offers by creating virtual worlds that participants can visit together and experience from multiple different perspectives.”

He also noticed that VR wasn’t always accessible. VR normally requires headsets. They can cost hundreds of dollars, generally have wires people might trip over, and cause nausea in a significant number of participants.

“This means that an educational experience that should be available to everyone is already restricted to some and not others.”

Scavarelli decided to use a programming interface that brings VR content to web browsers to create a platform that can be accessed using mobile devices and desktop PCs via keyboard controls.

“The desktop or mobile device experience may be less immersive, but it allows you to participate,” he says.

Exploring the Worlds of Viola Desmond

The result is a revolutionary prototype platform where users can experience a VR world simultaneously with others on a variety of devices. Circles currently offers a central hub, or “campfire,” with three worlds relating to Desmond, who was a cosmetics pioneer for black women in Atlantic Canada: her beauty salon, the Roseland movie theatre and Province House, the site of her posthumous mercy free pardon in 2010.

“The locations don’t have people in them,” says Scavarelli, “but with VR immersion you can move around, hear sounds and pick up objects. It’s like a living world that we’re visiting in shadow, so to speak.”

The central “campfire” hub.

The prototype platform was developed by a multidisciplinary team of six, headed by Scavarelli. It included a sound engineer, 3-D animator and a storyteller. Viola Desmond’s story was chosen for its topicality and to support diversity.

The project got a serious boost in 2018 when Scavarelli became one of just 100 selected from thousands across North America to participate in the 2018 Oculus Launch Pad program. Oculus, a VR industry leader that produced a headset that raised US$2.5 million on Kickstarter, flew participants to Menlo Park, California for a boot camp weekend of workshops and lectures, followed by three months of feedback and support from industry professionals.

“It was immensely helpful for moving the project along,” he says.

Accessibility, Social Scalability and Appeal

Informal pilot studies of Circles have been encouraging, and formal user studies in early 2019 are looking at accessibility, social scalability—how many people can beneficially participate—and appeal to students and educators.

When Scavarelli first came to Carleton as an undergraduate, he was enrolled in the physics program, determined to be a theoretical physicist. That focus soon changed.

“Instead of doing my assignments, I was on the computer teaching myself Photoshop and how to create in 3-D. It was the first computer that was my own—at home I shared one with my family—and I was amazed by its power.”

He switched over to the Interactive Multimedia and Design (IMD) program, a joint initiative between Carleton’s School of Information Technology and Algonquin College’s School of Media and Design. The program gives its students “a general knowledge base in everything technology,” says Scavarelli, who currently teaches a third-year IMD course at Algonquin. With both theoretical knowledge and hands-on application, graduates have an understanding of the industry that helps them adapt as it shifts and changes.

Then came a master’s degree in Human–Computer Interaction, where Scavarelli did a deep dive. Outside of class, he and a fellow IMD graduate formed Luminartists. Tired of seeing people locked into their phones out in public, they used technology to create a series of interactive art installations for special events around Ottawa that encouraged people to connect with each other and with the space around them.

This ethos of connection through technology animates the Circles prototype as well, and Scavarelli wants to see whether there’s a place for the platform beyond its current research phase. He’s reaching out to museums and other institutions for possible collaboration.

At the same time, he’s putting out feelers for funding partnerships, whether with industry, academia or other institutions—anyone who might be interested in taking the idea of web-based VR for education further.

“There may be a return on investment later on,” he says, “but the opportunity now is to be ahead of the curve on defining and creating what VR education can look like.”

Industry predictions are that VR is poised to go mainstream in the next couple of years. Already the headsets – some with touch sensors, some wireless – are available for a few hundred dollars, down from the thousands they used to cost.

In other words, according to Scavarelli, now is the time to start discussing ethical issues related to VR. Concerns range from the possible psychological effects of being immersed in a VR world with problematic content to personal data collection that could, down the road, lead to virtual cloning of participants without their permission.

Despite the dangers, though, for Scavarelli the potential benefits of VR are compelling.

“Ultimately art and technology are for everyone, to inform and inspire us and to better our sense of connection, and VR, by bringing people together into a virtual space, is really the ultimate form of doing that.”

Click here for more stories from the Carleton Newsroom.

Tuesday, January 8, 2019 in Faculty of Engineering and Design, Human-Computer Interaction, Interactive Multimedia and Design

Share: Twitter, Facebook