By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis

Fifty years ago, when Canada celebrated its centennial, eight-year-old Stephen Fai watched the ceremonies in the national capital on television from small-town Saskatchewan.

The copper-roofed Gothic Revival buildings on Parliament Hill — and the idea that such a place existed in his country — seemed magical.

Participating in projects that help showcase and rehabilitate the historic buildings of<br />Parliament Hill is a dream come true for CIMS director Stephen Fai.

Now an architecture professor and director of the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS), Fai and his students are using cutting-edge digital technologies to help the federal government document, rehabilitate and showcase these historic buildings through a series of collaborative projects that add another layer to Canada’s 150th birthday festivities.

“Doing this is literally a dream come true,” says Fai.

“We’re putting together material that people will be looking at from across the country.”

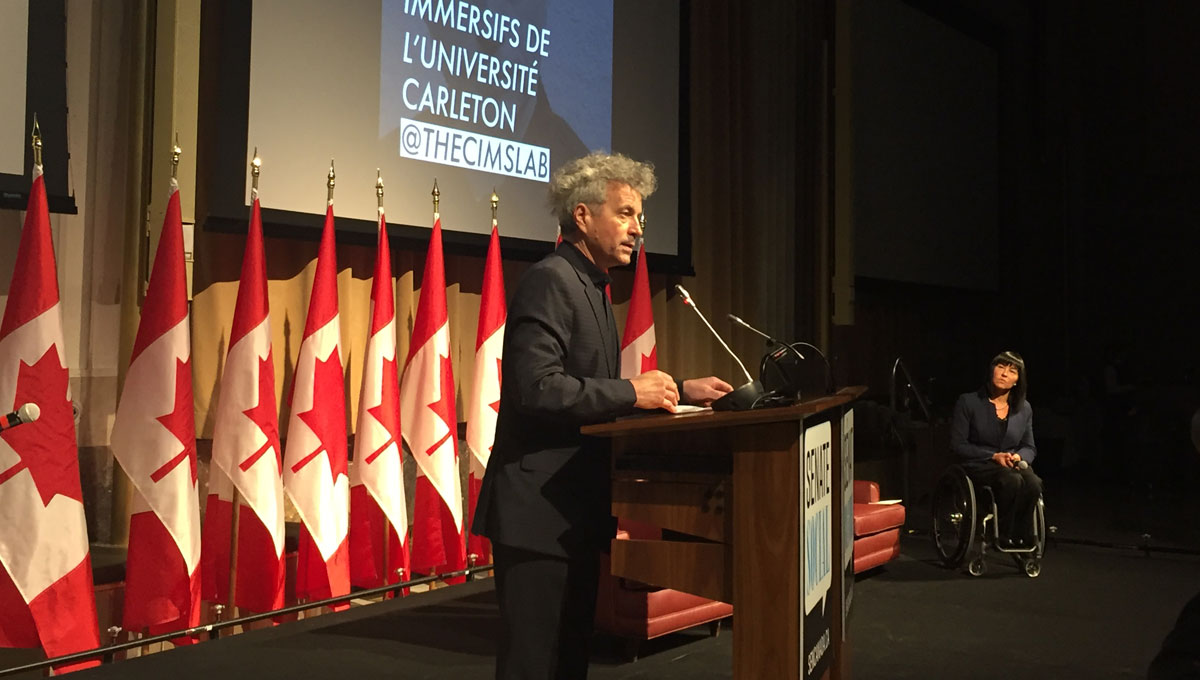

A virtual tour of the Senate foyer, antechamber and chamber — the first public component of the CIMS work — was launched at an event for politicians and the press in the Sir John A. Macdonald Building on Wellington Street on March 1.

Virtual Senate Tour Open to All

When major renovations begin at Centre Block next year and senators move into a temporary home in Ottawa’s former downtown train station, anybody with Internet access will be able to experience their iconic Red Chamber thanks to the CIMS virtual Senate tour.

Visitors can enter the virtual building and watch 360-degree 3D animations that bring to life the chamber’s artwork and architectural flourishes, from paintings, sculptures and the speaker’s chair to the four demonic “grotesques” perched over the main door. They can click on hotspots to read or listen to stories about the provenance of these features. And they can view a building information model that reveals that physical substructure above the ceiling.

Guests at a March 1 launch for the Senate’s new website test drive the virtual tour built by Carleton’s CIMS lab.

“Canada’s 150th anniversary is not just a time to reflect on the past — it is a chance to look to the future,” says Senator Leo Housakos, chair of the upper house’s Committee on Internal Economy, Budgets and Administration and chair of the Sub-Committee on Communications.

“The Senate’s virtual tour combines both by using technology to open up our institution to the public. Now all Canadians can thoroughly explore the Senate, delve into its history and appreciate the vital work the institution has been doing since Confederation.”

“This is a monumental achievement and we’re so happy to have worked with Carleton University to make it happen,” adds Senator Jane Cordy, deputy chair of both committees.

“There’s a lot of technical know-how behind this project, and Carleton students and their faculty supervisors had to put in considerable sweat equity as well. A lot of hard work, long hours and persistence went into developing this tour and we are grateful for their dedication.”

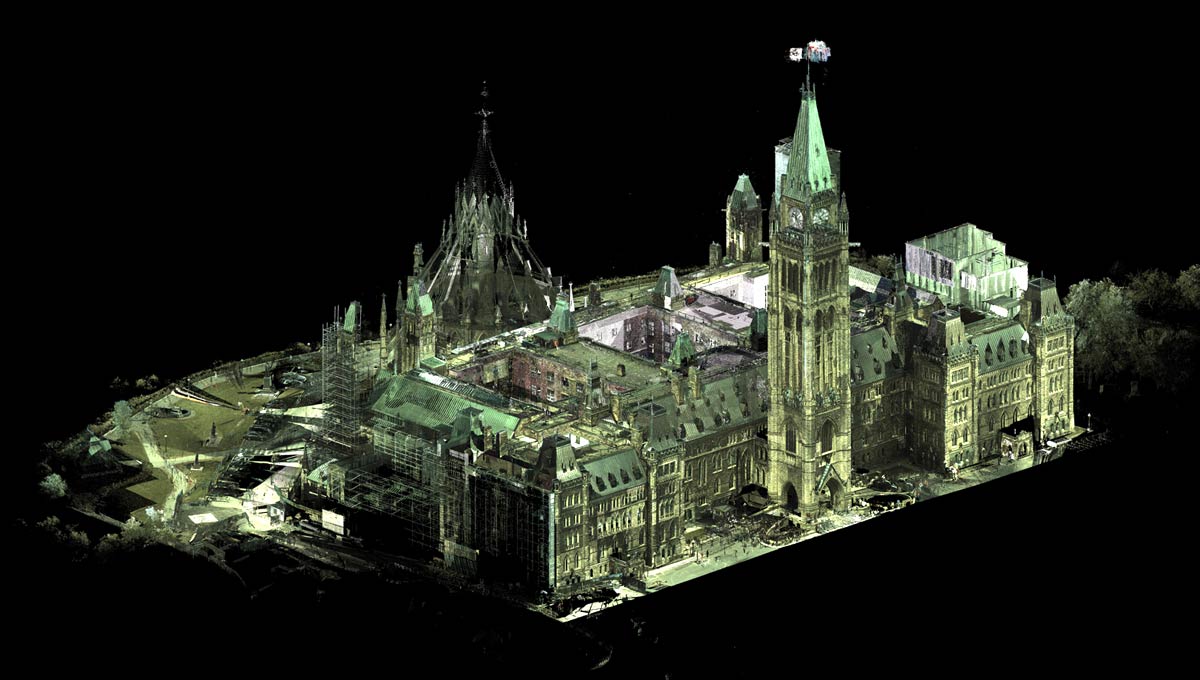

The virtual Senate tour, which the CIMS team created using 360-degree photographs, laser scans and photogrammetry of the exterior and interior of the building painstakingly captured during repeated visits over several months, offers a snapshot of the Carleton studio’s capabilities. And it hints at what else will be unveiled over the months and years ahead.

“This is a very new area of research for us,” says Fai.

“As a result, we’re expanding the number of directions our lab is exploring. Two years ago, it was mostly architecture and heritage conservation. Now it’s also sustainable design, interactive animation, coding, digital fabrication for reconstruction projects, and more.

“Being in the Senate chamber at 7 a.m. on a Sunday, when the only other person there was a security guard, that was quite an honour. It was gratifying for the students and me. But we haven’t had too much time to reflect on it — we’re too busy thinking about what’s next.”

A Buzz of Activity

Visitors to the 800-square-metre CIMS research centre, a collection of open rooms and workshops that occupy the fourth floor of the Visualization and Simulation Building in the southwest corner of campus, will be struck by the buzz of activity. The walls are adorned with maps, diagrams and blueprints; the desks are covered with cameras, microphones and large monitors; and a couple dozen students are either focused on their screens or talking to each other about the myriad tasks at hand.

Professor Fai introduces the virtual Senate tour at an event for politicians and the press in the<br />Sir John A. Macdonald Building on Wellington Street on March 1. (Photo: Jesse Plunkett)

The lab, established in 2002, is “dedicated to the advanced study of innovative, hybrid forms of representation and fabrication that can both reveal the invisible measures of architecture and animate the visible world of construction.”

Under the umbrella of the Faculty of Engineering and Design’s Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism, one of its goals is the “advancement and development of the tools, processes and techniques involved in the transformation of data into tangible and meaningful artifacts that impact the way we see, think and work in the world.”

Early projects at CIMS, funded by organizations such as Mitacs, included a digital model of Batawa, Ont. (a small town created by the Bata Shoe Company) as part of an imaginative community retrofit plan, and a resource management tool for the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation north of Ottawa. There were also biomedical models of mouse brains (supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research), and university buildings, to help managers visualize measures such as heat loss and electricity use.

Professor Fai introduces the virtual Senate tour at an event for politicians and the press in the<br />Sir John A. Macdonald Building on Wellington Street on March 1. (Photo: Jesse Plunkett)

This research revolved around what was then an emerging technology called building information modelling (BIM) — a conflation of architectural geometry and a database or databases. Gathering the metric information for BIM relied on a pair of techniques: laser scanning, which captures digital information about the shape of an object, building or landscape by using laser beams to measure the distance between the scanner and the target; and photogrammetry, which is defined as the science of using photographs (especially aerial images) to make precise measurements.

As equipment became more affordable and easier to use, CIMS began to develop increasingly complex and interactive models. “A motto we played with,” recalls Fai, who became the director of CIMS in 2007, “is `too much is never enough.’ How much information can you include and still have a workable model?”

Documenting the West Block

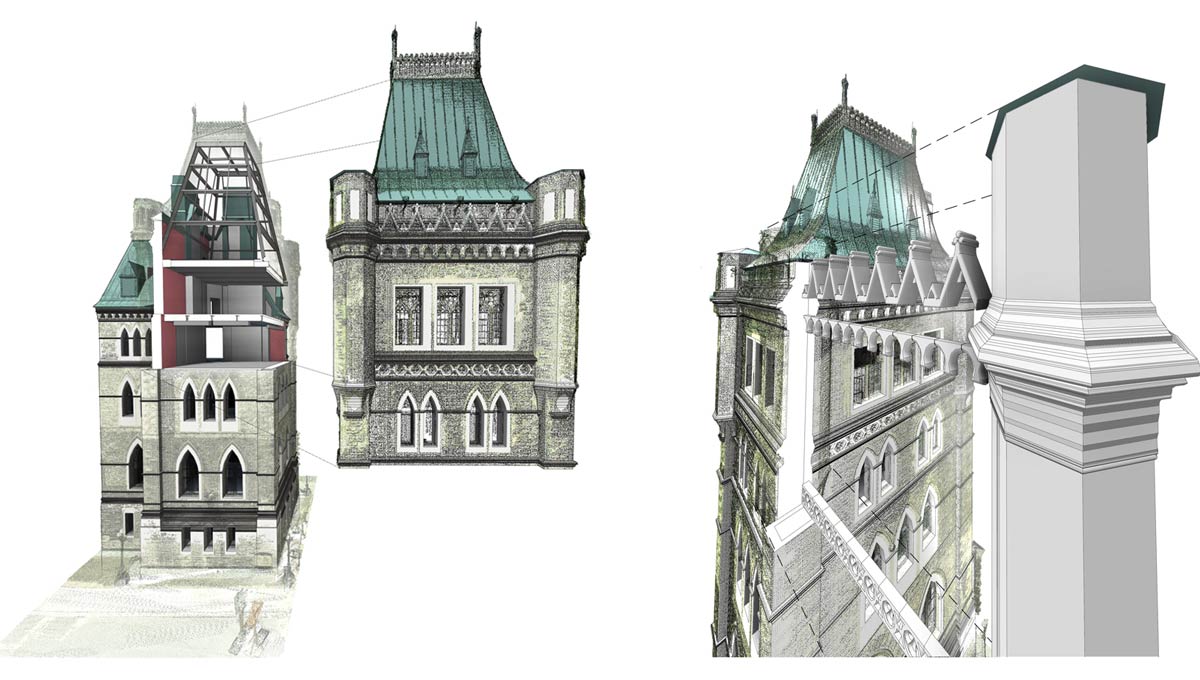

About six years ago, CIMS started to work with the federal Heritage Conservation Services agency on a study comparing the use of laser scanning and photogrammetry to fully document the West Block before its massive rehabilitation project, which began in 2011 and is scheduled to finish this year. (It’s the most complex rehab project ever undertaken on Parliament Hill.)

CIMS created a BIM of West Block’s exterior and interior — a tool that can be used both as a record of the building’s original structure and features, and as a guide for future maintenance and management.

Recognizing the value of these models, Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) expanded the partnership with Carleton to include BIMs of Centre Block and East Block, which are also undergoing major renovations.

The BIMs can be used by architects working on these projects. At the same time, the data and images behind them can also form the basis of immersive digital experiences like the virtual Senate tour and other collaborations underway with PSPC, such as an exhibit opening soon at the tourism information centre across the road from Parliament at 90 Wellington Street that’s part of PSPC’s sesquicentennial celebrations, with physical and digital elements as well as a “VR Bar” offering five different 360-degree experiences to visitors.

“A collaboration with CIMS allows the Parliamentary Precinct Branch to showcase its innovative approaches and use of state-of-the art tools and visuals to communicate PSPC’s role in building Canada for over 150 years,” says PSPC.

“The partnership has been very successful. Not only does it allow university students the opportunity to work on Canada’s most iconic buildings that are the seat of power and democracy, it also has the added benefit of building capacity in a technology industry for Canadians.

“The Centre Block, East Block and West Block projects… offer unique opportunities for young Canadians to contribute to these historic projects, and to build a solid knowledge base in Canada for heritage rehabilitation work, not only for trades such as stone masons, electricians, plumbers, carpenters, but also for students in the field of architecture and associated technologies such as BIM and 3D imaging. This partnership furthers Canada as one of the leading countries involved in modelling historic structures and utilizing knowledge gained to increase construction efficiencies.”

Fai breaks down CIMS’ digital workflow into five areas of research – digitization (laser scanning and photogrammetry), building information modelling, building performance simulation (energy usage maps), digitally assisted fabrication (which relies on a pair of robots — one large enough to cut stone — housed in the Azrieli School), and digitally assisted storytelling (web- and mobile-based narratives, virtual reality).

“Through these five processes, we can transform metric data into information that is operational for the architecture, engineering and construction industry, educational for the general public, and beautiful to look at or to hold,” says Fai. “We can take photographs of an object and use those photographs to create a physical replica of the object that was photographed. It’s an alchemical process.”

The Evolution of CIMS

Katie Graham has played a role in the evolution of CIMS since 2007, when about five students worked in the space — a fraction of the more than 30 who are in the lab these days.

Now in the third year of her PhD studies in architecture and team lead for the virtual Senate tour, Graham arrived in the lab as an undergraduate and remained involved through her master’s degree.

Students Abhijit Dhanda and Katie Graham have worked closely with Fai in the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS).

“Nobody has done the kind of work we’re doing in this way,” she says about the virtual Senate tour. “It’s been an incredible learning experience. As a team, we discuss everything and then go off and experiment.

“Other projects don’t have deadlines that are this intense — everything has to be presented in a certain way by a specific date.”

Scheduling access to the Senate when the house was not in session — and when there was enough light to capture images and no Christmas decorations visible — was a challenge for Graham, as was navigating the difference between mobile and web platforms for the finished products.

But the effort was worth it, and she’s excited about the prospect of her team’s work being exposed to an audience of millions in Canada and around the world.

“A lot of what we do is not for wide dissemination,” adds fellow student Abhijit Dhanda, who graduated from Carleton’s Architectural Conservation and Sustainability Engineering program last year and is working as a research associate at CIMS while waiting to hear about acceptance into the university’s Master of Civil Engineering program.

“So much of our work is very technical,” says Dhanda, whose responsibilities include visualizations and animations for the Parliament Hill projects. “We’re playing with different programs and are starting to understand how much we can do with the data. It’s very powerful and can be a tool for rehabilitation and public engagement.”

“Building information models show layers and layers of info,” says Graham.

“Now we can use the same tools to produce layers and layers of stories. It’s not just about making the data, but presenting it. This is a big, exciting shift.”

“We make sure students at CIMS have a chance to do everything they want to try,” says Fai. “Learning this range of skills is a great educational opportunity. We get them hooked — hooked on learning.”

And on the magic of adding their touch to the national story.

Thursday, March 2, 2017 in Innovation, Research, Technology

Share: Twitter, Facebook