By Dan Rubinstein

Last December, when Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its final report, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the federal government “is committed to walking a path of partnership and friendship” toward “a total renewal of the relationship between Canada and Indigenous peoples.”

Universities across the country are also on this path, not only in response to the commission’s 94 calls to action, but also as part of a broader transformation of their cultures and curricula. And though the journey will be long and challenging, Carleton has been working toward the goals of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for more than a decade, taking steps large and small to welcome Indigenous faculty, students and staff, and to ensure that Indigenous cultures, traditions and worldviews are respected and represented on campus.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau meets with the File Hills<br /> Qu’Appelle Tribal Council | Photo: Office of the Prime Minister

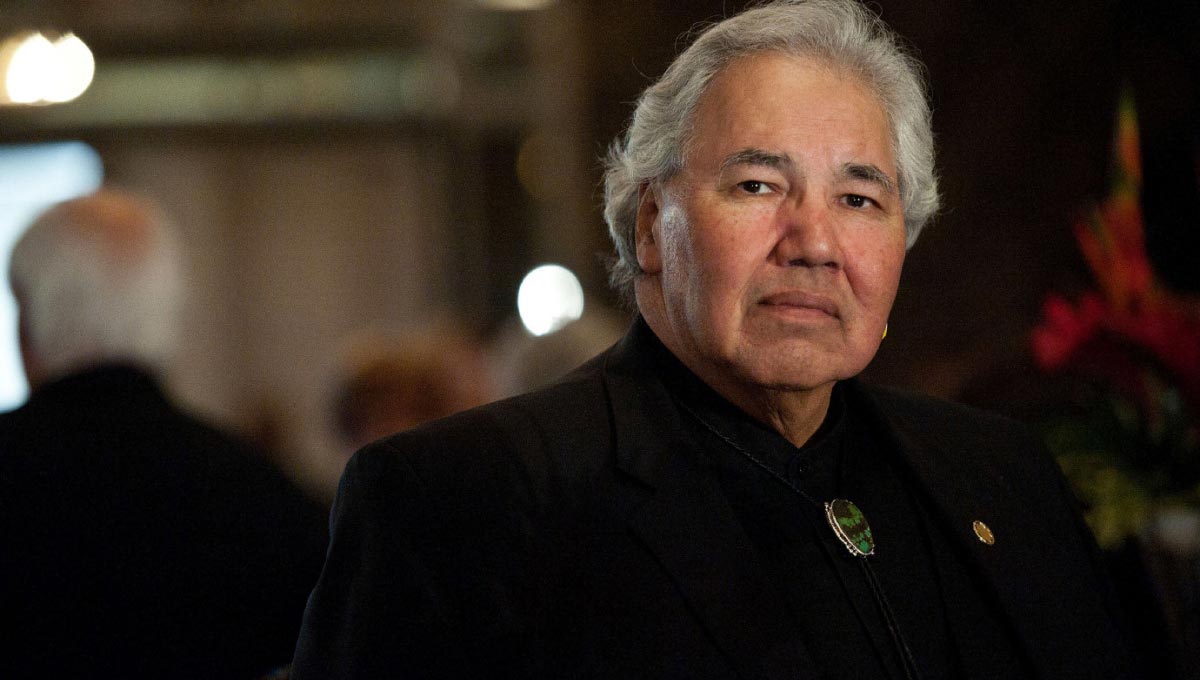

“We’ve made a lot of progress, but we still have a lot more work to do,” says Rodney Nelson, an Anishinaabe scholar who co-chairs both Carleton’s Aboriginal Education Council and the council’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission committee, which is responsible for co-ordinating the university’s response to the TRC. “This is about education in general. It’s about creating well-rounded individuals who know Canada’s history and contribute to our society — people who can recognize and stop injustices when they see them.”

Carleton’s TRC committee has several broad goals, among them a need to create more awareness about Indigenous histories and cultures, to be more inclusive toward Indigenous ways of teaching and knowing, to prioritize Indigenous languages, and to remove systemic barriers faced by Indigenous students.

Some of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations can be addressed in a fairly straightforward manner. For instance, number 86, which calls on Canadian journalism programs to include material on the history of Aboriginal peoples and the legacy of residential schools.

Although Indigenous perspectives and portrayals in the media are already part of a mandatory undergraduate journalism course and a professional practice course that all master’s students must take, Carleton has created a new course, Covering Indigenous Canada.

Anishinaabe scholar Rodney Nelson who co-chairs both Carleton’s<br /> Aboriginal Education Council and the council’s TRC committee.

It was developed and will be taught by Prof. Hayden King, an Anishinaabe writer and scholar who joined the School of Public Policy and Administration (SPPA) last May — part of a group of Indigenous faculty that has grown from two to nine members over the last dozen or so years.

In response to Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendation No. 57, which calls on governments to provide education to public servants on the history of Aboriginal peoples, the SPPA hosted a panel discussion in early September. At the well-attended event, Carleton faculty shared their expertise with public sector leaders and dozens of students who may one day work in the field.

But much of the university’s response to the TRC won’t be so specific. Unlike other schools, such as the University of Winnipeg, which this fall instituted a mandatory Indigenous course requirement for all new students, Carleton is adopting a more organic approach to Indigenizing its programming and services — an approach that, in many ways, continues the evolution that’s already underway.

“A lot of the ideas in the TRC are no surprise,” says Nelson. “They’ve been put forward by organizations like the Assembly of First Nations for a long time.

“We’re not comparing ourselves to or competing with other universities. We just want to do what’s right.”

It’s 2016 — know your history

Several recent changes embody the overarching transformation at Carleton, including the officially renamed School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies, formerly Canadian Studies, which will be launching a Bachelor of Arts (combined honours) program in Indigenous Studies next fall.

The new program will offer Indigenous and non-Indigenous students an opportunity to study the historical and contemporary experiences of Indigenous people, both in North America and internationally.

“Indigenous people have been here since time immemorial,” says co-ordinator Jennifer Adese, an Otipemisiwak/Métis professor who joined Carleton in 2012 as the inaugural New Sun Visiting Aboriginal Scholar. “It’s 2016. You don’t have the option to live in a place and not know its history.”

Meanwhile, Carleton’s Indigenous Policy and Administration (IPA) program, which admitted its second cohort of students this year, offers a pair of graduate diplomas, as well as an Indigenous concentration within its Master of Policy and Administration.

The program is intended for “leaders who can work in this fluid environment with a level of cultural competency and an understanding of Indigenous history, law, economics and politics that go beyond a simple awareness of Aboriginal issues.”

In a similar vein, last June the university hosted the week-long Carleton University Institute on the Ethics of Research with Indigenous Peoples.

The institute, which grew out of a three-day pilot in 2014, is intended to “build understanding among researchers of all kinds — students, faculty, governmental — about good ethical practices when doing research in Indigenous communities,” says Prof. Emerita Katherine Graham in the School of Public Policy and Administration and co-facilitator of the gathering alongside recently retired journalism professor John Medicine Horse Kelly, a member of the Haida Nation and one of the university’s first Indigenous faculty members.

“There’s a need for stronger relationships, for reciprocity,” says Graham.

“Research is not about taking anything away — it should be about an exchange, about co-creating and co-owning knowledge.”

Underlying these initiatives and programs is a new attitude at Carleton, an inclusiveness embodied by the Douglas Cardinal-designed Indigenous centre, Ojigkwanong, which opened on the ground floor of Patterson Hall in 2013 and is managed by the university’s Centre for Aboriginal Culture and Education.

John Medicine Horse Kelly, a member of the Haida Nation and one of<br /> Carleton University’s first Indigenous faculty members.

Ojigkwanong has work/study space and a kitchen, a recognition of the central role played by traditional foods in Indigenous cultures. The centre hosts events and orientation sessions, serves as a gateway to local resources, and is a home away from home for the 600 or so Indigenous students on campus.

All of these developments not only fit within Carleton’s Aboriginal Co-ordinated Strategy, which was approved by the Senate in 2011, but also the overarching Strategic Integrated Plan, which lays out the vision for the university from 2013 to 2018, and calls for the expansion of Indigenous programming and enhanced relationships with Indigenous communities.

“The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report comes at a time when Carleton is well into the implementation of its Indigenous strategy,” says Vice-President (Academic) Peter Ricketts. “The recommendations of the TRC are a wake-up call to all Canadians. They challenge universities to step up and address issues of injustice and the consequences of that injustice. Carleton’s TRC committee will ensure that we play an active role in the journey towards reconciliation.”

“Carleton has a responsibility to illuminate and explore the truth about the histories and cultures of Indigenous peoples,” says Graham. “We also have a responsibility to help build understanding that reconciliation is a complex process that we all must think about and engage in. Our actions as a major public institution will need to clearly reflect ongoing commitment at the highest levels of the university while, at the same time, enable the creation of diverse paths throughout Carleton for us to live together in a better way.”

The evolution of

Indigenous programming

Sheila Grantham has had a close-up view of the progress at the university over the years. In fact, like Rodney Nelson, she has helped to drive these changes.

Grantham, who co-chairs Carleton’s Truth and Reconciliation committee with Nelson, has Métis and Anishinaabe ancestry. Currently a PhD candidate in Canadian Studies (exploring decolonizing pedagogies and how to create inclusive spaces for students) and working as the IPA program’s community co-ordinator and administrator, Grantham entered a different landscape when she arrived at the university as an undergraduate in 2001.

Services for Indigenous students were limited, so Grantham and a group of students met with then-president Richard Van Loon to call for changes.

Some movement was already under way, as documented in a detailed report called “A History of Aboriginal Programming at Carleton University” written by Canadian Studies PhD student Jo-Anne Lawless under the supervision of Prof. Kahente Horn-Miller.

Sheila Grantham (Canadian Studies), Vanessa Stevens (Psychology) and Becky Mearns (Sociology) attended the Indigenous Graduate Honouring Ceremony held at the Museum of Civilization at the end of April. | Photo: James Park

A Native Studies Research Centre had been established in 1990, Lawless writes, and in 1993, Madeleine Dion Stout, a Cree woman from Alberta, became a professor in Carleton’s Canadian Studies Department and was the founding director of the Centre for Aboriginal Education, Research and Culture.

In 1999, according to the report, the university, in collaboration with Nunavut Arctic College, initiated an Inuit Law program. During its brief tenure, the program offered additional support to Inuit students experiencing difficulty with the transition to mainstream education.

SPPA also offers a Certificate in Nunavut Public Service Studies, which not only gives practicing public service employees in the northern territory special training, but has provided the university with valuable lessons and models for supporting students in northern and remote locations.

Carleton’s Aboriginal Enriched Support Program (AESP), established in 2002 and now co-ordinated by Rodney Nelson, evolved directly from the initial outreach to Inuit communities and students, offering personalized support to Indigenous students to ensure a successful entrance to university studies.

Course offerings at Carleton have evolved too. Steps toward including Indigenous content in classes had started in the mid-1960s, although Aboriginal Studies as a discipline wasn’t introduced until 1995.

The program was first co-ordinated by Simon Brascoupé, a member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation north of Ottawa. “Individual departments at Carleton offer[ed] courses concerned with Aboriginal issues,” the history report said. “Growing interest in Canadian First Peoples … promoted a gradual increase in courses about Aboriginal cultures and an increase in related activities on campus.”

The arts have also played a role in the university’s transformation. The Carleton University Art Gallery has been exhibiting and collecting the work of Indigenous artists since its founding in 1992, and last year hosted “Walking with Our Sisters,” a commemorative art installation for missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Since 2002, Carleton has also hosted the annual New Sun Conference on Aboriginal Arts, a popular public forum for people from First Nations, Métis, Inuit and non-Indigenous communities to explore themes such as “healing through the arts” and “transforming traditions” by sharing their expertise in photography, painting, sculpture, filmmaking and other arts.

Student support builds over the years

In the early 1990s, an Indigenous student lounge was opened on the 20th floor of Dunton Tower, but it was a barebones space that did not have a working computer. The lounge was eventually relocated to the tunnels below the Tory Building, where working computers were acquired and a full-time Aboriginal liaison position was created, but it was a far cry from the scale of support and services offered through Ojigkwanong.

“There was support from administration,” recalls Grantham, “but also a gap in terms of knowing how to move forward.”

To close this gap, Grantham and Nelson were two of the founders of a student organization called Word Warriors that provided peer support to Indigenous students and encouraged Indigenous pride.

Ojigkwanong has work/study space and a kitchen, a recognition of the central role played by traditional foods in Indigenous cultures. The centre is a home away from home for the 600 or so Indigenous students on campus.

Word Warriors convened Carleton’s first Indigenous academic conference in 2007. “It was a real opportunity for Indigenous students to feel empowered,” says Grantham, “and it helped demystify the university for the Indigenous community at large, so they could start to see it as a place where they too could belong.”

Ultimately, these student-led efforts and support from administration spawned Carleton’s Aboriginal Vision Committee, which was active in 2008 and 2009, and its Task Force on Aboriginal Affairs, which was in place from 2009 to 2013 — precursors to today’s Aboriginal Co-ordinated Strategy and Aboriginal Education Council.

“It was the community coming together and saying, ‘These are our priorities — a lot can be done to address the needs of Indigenous students,’” says Grantham, describing an environment within which Indigenous students, faculty and staff worked with local Indigenous organizations to advocate for change.

“The recommendations of the TRC can’t be implemented overnight,” says Grantham, “but now these ideas are shared university-wide, and we’re receiving tremendous support from the administration. There is a lot of need, but also so much willingness and cooperation to move forward together.”

Lawless’s report notes the role played by Carleton’s senior leaders.

“Little is accomplished in academia without the support of administrators,” she writes, “and Carleton’s path toward the inclusion and promotion of Indigenous programming is no exception. University President and Vice-Chancellor, Roseann O’Reilly Runte, was a strong proponent of improving Aboriginal education at Carleton University, from her arrival in 2008, and was a leading catalyst for change in Indigenous programming.

“The following year, Peter Ricketts took on the post of Provost and Vice-President (Academic) and immediately put into action his desire to make Carleton a more open and welcoming destination for Aboriginal students. Ricketts recognized the need to develop a clearer strategy that would make the university as attractive a destination to Aboriginal students as smaller and less urban universities.”

Carleton professor encourages Canadians to read about Truth and Reconciliation

Zoe Todd, a professor who joined Carleton’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology last year, responded to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in a unique way.

Todd, a Métis scholar who does research on fish, colonialism and legal-governance relations between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian state, was one of the organizers of the “Read the TRC” project — a crowd-sourced request for people to record themselves reading part of the commission’s 388-page executive summary and post their videos online.

The project, an effort to democratize access to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action, drew praise from TRC Commissioner Marie Wilson. But Todd, who considers the TRC recommendations a “fundamental challenge to the structure of Canadian universities,” is also incorporating its spirit into her teaching in more holistic ways.

Carleton University’s Aboriginal Centre, Ojigkwanong hosts the Social Sciences and Humanities<br /> Research Council (SSHRC) as it launched new initiatives to provide broader support for Aboriginal research.

At the start of one course, for example, her students are asked to orient themselves to the Ottawa River watershed, and the Indigenous communities within the watershed. This helps them understand that they (and the university) are not only on unceded Algonquin territory, but also situated within a natural ecosystem that encompasses many Indigenous communities.

“I’m trying to sensitize students to see reconciliation as something that’s about relationships,” says Todd.

“Relationships between communities, and relationships between people and the natural world.”

In a second-year anthropology class, Todd asks students to pick one of the TRC’s calls to action and to think through the implications of that recommendation on their work as a professional in the discipline of their choice, such as a journalism or social work.

Students in the social sciences and humanities will get more exposure to these types of assignments, she says, and though there is a need in other fields, “making things mandatory is a good recipe for making people resent them.”

Universities need to be careful when implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to actions, says Todd, noting that Carleton has been steadily developing relationships with local and regional Indigenous communities and elders. “We’re making these connections implicit,” she says. “All of us can bring these ideas into our classrooms in various ways, using the skillsets we have as academics. Things are in motion.”

Governments need to follow through, however, and provide the resources required to support this shift. All of the heavy lifting can’t fall upon a handful of Indigenous faculty members.

There’s a need for long-term funding for Indigenous tenure-track positions, for Indigenous grad students, and, as Todd says, “a space for dynamic academic positions that cross disciplinary boundaries.”

Responses to the TRC

need to engage students

Hayden King, the newest Indigenous professor at Carleton, was drawn to the university because of its growing Indigenous faculty and curriculum.

As a prominent public intellectual, he has an opportunity to contribute to national discussions and help inform public policy.

King is open to mandatory Truth and Reconciliation Commision-related courses — or mandatory Indigenous content courses generally — but it is important to him to see responses to the TRC dispersed throughout Carleton’s faculties and departments in ways that truly engage students.

Carleton University hosts an evening with TRC chair Murray Sinclair on Oct. 3

“The relationship between Indigenous peoples and Canadians is central to the country,” says King. “But reconciliation means different things to different people. The legacy of residential schools is endemic and more education will hopefully help break down systematized racism and stereotypes.”

The next chapter in Carleton’s journey begins on Monday, Oct. 3, when the university hosts an evening with Senator Murray Sinclair, who chaired the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In his talk, which will be followed by a Q&A and reception, Sinclair will discuss how all Canadians can walk side by side as we take more steps on the long path towards true reconciliation.

Monday, September 26, 2016 in Indigenous, Public Policy

Share: Twitter, Facebook