By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Chris Roussakis and Northern Nomad

Under an overhang of Carleton University’s Architecture Building, a pair of attractive wood-framed structures are taking shape. Small in size but ambitious in scope, they’re energy-efficient tiny houses embodying an amalgam of research, education and environmental stewardship. Here’s the story of one of them – the Northern Nomad.

Josh Reinhart is standing beside a rectangular 220-square-foot half-finished house clad in pink insulation panels, trying to figure out how to mount a bulky two-foot by three-foot inverter charger for the solar equipment to the exterior of the building.

Before coming to Carleton, the second-year Architectural Conservation and Sustainability Engineering student spent half a dozen years as an electrician in Calgary’s construction industry. A passion for sustainable housing sent him back to school.

But he didn’t know he’d have an opportunity to get involved in a hands-on project as inspiring as the Northern Nomad tiny house.

“When I was working in construction, I saw that there was so much more we could be doing to reduce our environmental impact and our reliance on oil,” says Reinhart, who has become the electrical lead on Northern Nomad’s team of about a dozen student builders led by Prof. Scott Bucking from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism.

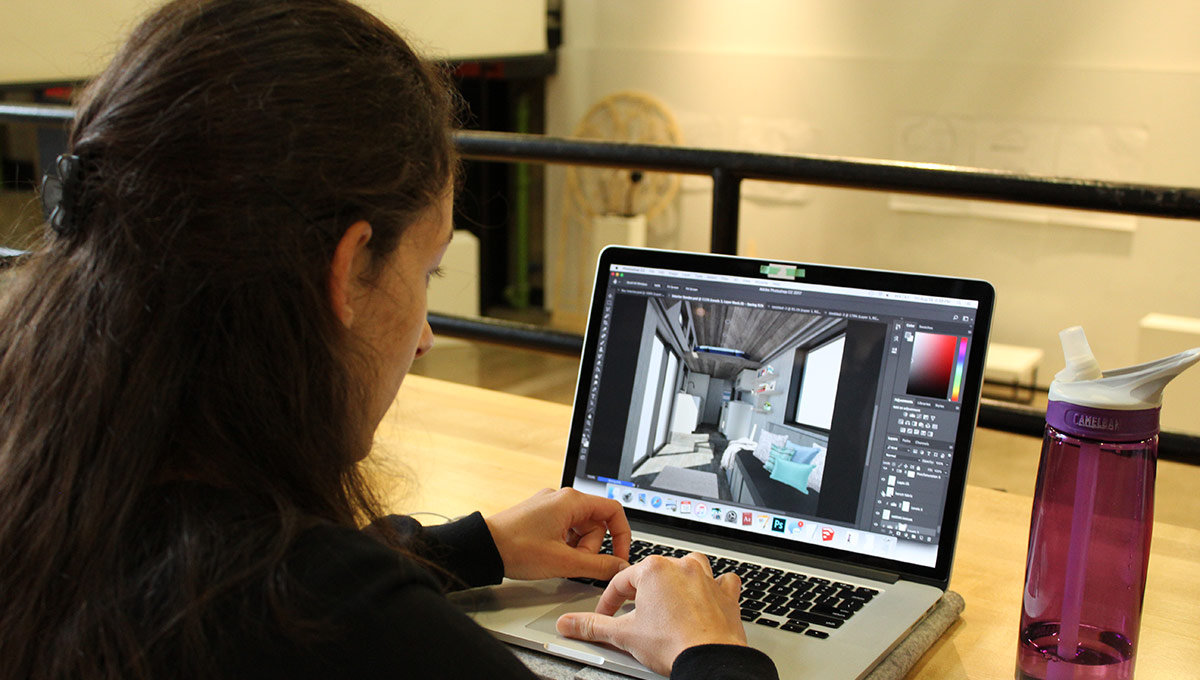

“For an engineer, it’s so valuable to be able to participate in a building project,” says Reinhart. “It’s one thing to draw a design on a computer, but it’s something else to put it together in real life.”

Reinhart and his fellow students have a diverse range of experience and interests, and are contributing to the project in different ways. Brigitte Martins has done the architectural renderings and construction drawings. Seungyeon Hong is modelling the house’s energy use. Eric Ho is helming its smart home features. Sandra Lunn is handling project and budget management. Paige Waldock is in charge of the water systems. And so on.

Meeting the crew, a rousing Hollywood plotline comes to mind: a team of super-talented burglars, each with a specific skill, being pulled together for one final against-all-odds heist.

Except the Northern Nomad students, with guidance from Bucking and support from external organizations and companies, are building a habitable real-world house. And their overarching goal — to demonstrate and test the effectiveness of important changes we can make in the face of climate change — has much higher stakes than any fictional film.

A Tiny House That Pushes the Limits of Sustainable Building Design

Northern Nomad was launched as a capstone design project last November by a group of five senior engineering students supervised by Bucking. They wanted to build a tiny house, according to a description for a FutureFunder campaign that raised nearly $12,000, and “push the limits of sustainable building design in Ottawa.

“We will be exploring ways in which new and innovative technologies can be integrated into a sustainable building,” they wrote. “Our hope is to reduce the impact of greenhouse gases on the built environment in response to climate change.”

Canada’s building industry is responsible for 35 per cent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions, 33 per cent of national energy consumption and 35 per cent of waste that’s sent to landfill. By using photovoltaic panels instead of natural gas and the electrical grid, by using super-efficient insulation, and by collecting and transforming airborne moisture into potable water, Northern Nomad’s intent is to be net-zero for both energy and water usage.

“Our primary goal is to build an autonomous house,” says Bucking. “How we do that on an energy side is easier than how we do it on the water side. And if you have a surplus, you can supply it back to the grid.

“Ultimately, we want people to feel empowered, and see that they can make a difference.”

When the initial designs were drawn, Bucking told the students that if their plan was compelling enough, he would help them go from concept to reality. But building a house, even a very small one, takes money — in this case, about $70,000 to $80,000.

Thankfully, Northern Nomad caught the attention of Janet and Leo Lefebvre, who run Ottawa’s Borealis Foundation, a sustainability-oriented non-profit that for the past five years has been supporting environmental initiatives on campus like the Solar Decathlon, other capstone projects and scholarships for engineering students.

“When we started meeting people at Carleton and hearing about all of the great projects underway, the lightbulb went on,” says Leo. “We’re not a big foundation, but we can be strategic with our support, and we realized that we could help students — the voices of the future.”

That philanthropic philosophy aligns closely with Carleton’s mission to be “Here for Good,” to serve the greater good of society through higher education.

“We believe that education is a powerful tool and a way to enact change,” says Janet. “We also want to focus on local communities and to make a difference in our own backyard.”

The Borealis Foundation provided a substantial portion of the Northern Nomad budget, and Bucking and his expanding group of students got ready to build.

“Climate change is a real issue and is increasingly at the forefront of people’s minds,” says Leo. “We want to support innovative projects that help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But beyond that, Northern Nomad is bringing together students from different disciplines to work as a team, which is really going to prepare them for the real world.”

With the Borealis Foundation on board, Bucking secured contributions of free or at-cost material from an array of suppliers, such as triple-glaze argon-filled windows donated by JELD-WEN, lumber from Manotick’s WoodSource, and polyurethane spray foam from the Canadian Urethane Foam Contractors Association and Insultech Insulation Specialists Inc.

Bullfrog Power also signed on to help support the project. “The Northern Nomad tiny home is an important opportunity for the engineers of tomorrow to push the boundaries of sustainable building technologies in Canada,” said the company’s CEO Ron Seftel. “Bullfrog Power, through its community renewable projects program, contributed funding to the project on behalf of the thousands of individuals and organizations across Canada that choose green energy with (our company).”

Generating Interest and Spreading the Word

Because the house is being built outdoors, it has caught the eye of both passersby and the media. The Northern Nomad story has been told on CBC TV and other news outlets, and as Brigitte Martins wrote on the team’s blog, “many people stop to watch us work and ask questions, ranging from Carleton professors and staff to students and parents, young and old. It is amazing to see how interest can be generated and how word can spread.”

Prof. Bucking convened one of the first Northern Nomad team meetings in early July before the trailer where the house now rests was scheduled to arrive on campus.

A Carleton and Concordia graduate who studied both engineering and physics and understands the overlap between the two fields, Bucking’s PhD research included energy modelling for net-zero homes, and he built houses in eastern Ontario before becoming a full-time professor, making him ideally suited to this project.

He’s also content to step back and let the students learn by dealing with problems as they arise, which is inevitable during every custom construction project. And Northern Nomad is certainly unique.

The house will include, among other distinctive features, a sleeping loft that can be slid out of the away along horizontal tracks; five tanks that can contain 900 litres of water beneath the raised floor for storing purified water distilled from the air with an off-the-shelf damper, fan and dehumidifier; photovoltaic panels that cover the roof (instead of metal or another durable material) which can produce power and potentially supply electricity to the provincial grid; and a ceiling made from wood salvaged from a century-old Ottawa Valley barn.

“We can build this for around $70,000 — the price of a very nice car,” said Bucking. “Which is cool that you can build a house for the price of a car.”

The students come from programs such as Architecture, Mechanical Engineering, Civil Engineering, Electrical Engineering, Sustainable and Renewable Energy Engineering, and Architectural Conservation and Sustainability Engineering.

“To get this house built, we’re going to have to work as a team,” Bucking said during the early July meeting. “This is the calm before the storm. Something will go wrong — it’s just a question of when.”

Building the Tiny House

As soon as the trailer arrived on campus in late July, the Northern Nomads students started framing the house atop its mobile base. The walls went up quickly, and then they started working on the electrical wiring and plumbing.

By mid-August, the framing was almost finished, and they were days away from installing doors and windows and starting to work on the interior.

Eric Ho, a third-year student in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering’s Sustainable and Renewable Energy Engineering stream, was outside the house, cutting oriented strand board (OSB) for sheathing the roof. (Bucking had wanted to use Canadian plywood, part of the project’s bid to use as much local and environmentally friendly material as possible, but this summer’s major forest fires in Western Canada limited the supply of plywood, forcing Northern Nomad to go with Canadian OSB instead — one the many hurdles encountered throughout the material acquisition and construction process.)

Ho, who is doing a minor in Computer Science, is largely responsible for the house’s smart features, which will allow lights, appliances and other systems to be controlled and monitored remotely.

Today, he’s happy to be helping with the physical work — very different than all of the time he spends sitting at a computer. “It’s a different kind of pressure than what you feel when you have to finish a paper,” he says. “Like, the spray foam installation is coming in two days and everything has to be ready for it by then! My other classwork is rewarding, but not as exciting as building an entire high-tech house from scratch.

“There are a lot of different skills to learn,” Ho adds. “And there has been a lot of real-life human error.

“We’re getting really good at cutting and measuring now.”

While Ho was cutting OSB, Bucking, who can see the construction site from a window just outside his office in the Canal Building, was busy on the phone, negotiating deals for material from suppliers and sponsors — and handling the occasional cold call from people who want to purchase the house when it’s finished.

The plan, for now, is to tow the house to an open patch of land beside the Urbandale Centre for Home Energy Research, near the northern tip of campus, and for a group of Bucking’s fourth-year engineering students to monitor the house’s performance over the fall and winter.

“It’s a multidisciplinary team,” Bucking says about the next phase of the project. “One group will look at the trade-offs between the architectural design and engineering systems. The other will be able to give us an idea about the carbon payback of a tiny house.

“Once we get some data in, we’ll be able to tell pretty quickly how efficient the house is — for example, how air tight is it? Then the students can take the lessons learned from this house and hopefully help us come with up with an even better tiny house design.”

The house was part of Ottawa’s Green Energy Doors Open showcase on Sept. 30. Though the event was at Lansdowne Park, attendees were encouraged to come to Carleton to tour Northern Nomad, another tiny house under construction beside it, and the Urbandale eco-house.

Ultimately, Northern Nomad could be donated to a charity, or sold to raise money for future sustainability research, including perhaps more tiny houses. But first, it has to be finished.

Maximizing Northern Nomad’s Energy Efficiency

On a hot afternoon in mid-September, Connor Ruprecht — a second-year Sustainable and Renewable Energy Engineering student — and Seungyeon Hong are at the house, attaching charred cedar panels to the exterior.

Hong, a Civil Engineering graduate who’ll be starting a master’s degree on energy modelling with Bucking in January, has developed models to help maximize Northern Nomad’s energy efficiency. But he also designed and built the wooden arch at the front of the house, having apprenticed with an artisan timber framing crew in his native South Korea.

The project not only provides Hong with training for his personal dream of designing and building his own house, it also brings him closer to his career aspirations. After learning about sustainable design in his final year as an undergraduate, he knew he wanted to work in the sustainability industry.

“I had a strong desire to design and build more sustainable buildings, and I was searching for ways to get experience in this field,” he says. “But finding those opportunities becomes more difficult once you’re out of university. I am extremely fortunate to be a part of Northern Nomad, as it has given me that field exposure and led to further studies in this exciting field.

“This project is the complete embodiment of experiential and peer-to-peer learning,” he adds. “Everybody on the team has been learning from each other.”

To Hong, the house, with its mix of old and new elements, such as the salvaged century-old barn boards juxtaposed against high-tech LED lighting, as well as its energy autonomy and nomadic essence, also embodies the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, a hard-to-define idea which means “an appreciation of beauty within the imperfections and transience found in natural cycle of growth and decay.”

It’s an important concept for people to embrace as we attempt to address the challenges of global warming and find a path to sustainability in a rapidly changing world.

Friday, October 13, 2017 in Architecture, Engineering, Environment and Sustainability

Share: Twitter, Facebook