By Matt Gergyek

Photos by Kanina Holmes

Madeline Lines, a fourth-year Journalism student at Carleton University, knows the golden rule of her craft like the back of her hand.

“Objectivity, objectivity, objectivity.”

That’s by no means a bad thing — with mistrust of the journalism industry growing across the globe, according to 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer, factual, impartial reporting rooted in objectivity is a journalist’s Holy Grail in the shifting media landscape.

But after spending a month in Canada’s North as part of the recently launched Stories North course in the School of Journalism and Communication, Lines emerged with a new understanding of what it means to be a practicing journalist in Canada and around the world.

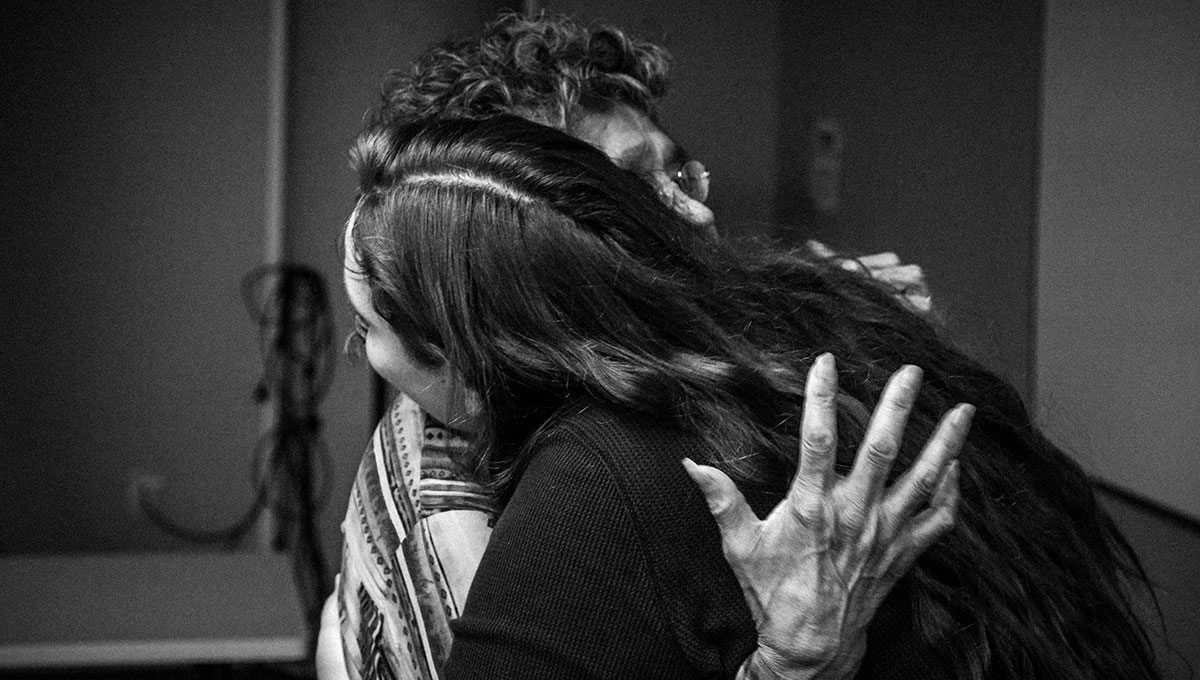

Julia Moran, a fourth-year Journalism student, hugs Bessie Cooley, a Tlingit elder who spoke to Stories North students about her experiences at a residential school.

“We developed a journalism of empathy,” she explains. “The push to be objective, which I see as being totally valid, can cause people to . . . neglect empathy, when I think it can be a tool to learn about the greatest stories you possibly can.

“It becomes complicated when a residential school survivor breaks down in tears. Are you supposed to comfort them? When it comes down to that, I will always be a human being before I’m a journalist and that’s something I won’t compromise.”

Stories North, the creation of Journalism Prof. Kanina Holmes, sent 21 upper-year undergraduate and master’s students to Whitehorse for the month of July. They travelled to communities throughout Yukon and northern British Columbia with a goal of expanding the narratives surrounding reconciliation by listening to First Nation stories and providing platforms for their voices and experiences to be heard. The course aims to increase intercultural understanding, empathy and mutual respect.

Educating Students in Indigenous History

Holmes first came into contact with Indigenous and northern storytelling when she worked for CBC North in the Yukon in her reporting career, sparking early ideas for Stories North.

“I remember covering these important Indigenous stories and feeling that this is hugely important, but do we actually have the background to understand this?”

When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) released its final report in late 2015, including calls to action for journalism schools across the country to educate their students on Indigenous history and issues, Holmes sprang into action.

“Journalism is an extractive craft,” Holmes says. “We go in, we get our stories and we leave. I’m not going to be able to change that model completely, but I’m trying to find a way for us to spend more time on our stories and with our sources to understand the nature of storytelling. It’s looking at journalism as more of a collaboration.”

Students who took part completed a course on Indigenous people in the Yukon, heard testimonials from residential school survivors, created photo essays from covering the Adäka Cultural Festival (a First Nations art and culture festival) and created 60-second videos at Atlin Arts and Music Festival.

This is the second year the course has been running, funded this year by a donation of close to $250,000 from the Mastercard Foundation. This year’s course revolved around the theme of connection.

Stories North: Exploring Personal Connections

One of the stories covered by Isaac Würmann, who graduated from the Journalism program this year and now works with CBC Manitoba, emphasizes this theme perfectly.

Würmann’s aunt, Karrie, was adopted into his family in 1968 at 10 months old from the Carcross/Tagish First Nation during the Sixties Scoop — a Canadian government-sanctioned program in the late 1950s to the 1980s where Indigenous children and youth were separated from their families and adopted by non-Indigenous families, both inside and outside of Canada.

As a result, the more than 20,000 adoptees were often stripped of their culture. Today, many still deal with the mental and emotional damage.

For his final project, Würmann decided to document Karrie’s second return to Yukon and her experience reconnecting with family members, friends and her culture.

“I was put into foster care five days after I was born and, even at that age, you feel the separation,” Karrie tells Würmann in the audio documentary. “It wasn’t a great foster home. They didn’t feed me very much, and according to what my mom said they didn’t show me any love; I was just another kid they had to look after.”

For Würmann, the experience opened his eyes to the reality of being an Indigenous person in Canada.

- Stories North

- Three Carleton Student Projects in the Top 10 of the TVO 2018 Short Doc Contest

- Indigenous Use of Media

“I think it’s important for people who are non-Indigenous to see how they are connected to these horrible experiences that can seem abstract when you’re sitting in a classroom,” Würmann explains.

“If every white settler in Canada saw that they were somehow connected to the residential school legacy, people would care more about making things better.”

Würmann says one of his biggest takeaways was the understanding of the diversity of ways of life among Indigenous people in the North.

“Every community is different and every community has a different story,” he says. “To paint all of them with the same brush does a disservice to those communities.”

Understanding Trauma and its Impacts

Journalist and educator Matthew Pearson also played an important role as a guest instructor in the course.

Pearson, a part-time instructor at Carleton, conducted research while based at the university this spring to help journalism students and working journalists better understand trauma and its impacts, thanks to the 2017 Michener-Deacon Fellowship in Journalism Education.

During the course, Pearson delivered a seminar on what he calls “trauma-informed journalism.”

Matthew Pearson

“I try to teach students how to cover traumatic incidents and report on people who experience trauma with a better understanding of what trauma is and how it affects the folks we report on, as well as how it can effect us,” he explains.

Aligning with the course’s aim of giving back to communities that journalists cover, Holmes asked Pearson to give a similar seminar to reporters based in Whitehorse.

“We need to be careful not to draw a direct line between reporting on Indigenous people and trauma, because I think it’s important that we never define someone on the trauma they survived,” Pearson says.

“But at the same time, we have to acknowledge that there’s a history in Canada around residential schools, around other forms of racism that have persisted, that have meant that there are people who are Indigenous who have experienced multiple layers of trauma throughout their lives.”

A Necessary Education

Terra Tailleur, a Journalism professor at Halifax’s University of King’s College, joined the team to provide her expertise in multimedia journalism and online packaging.

“I don’t think you can be a responsible journalist in Canada without knowing the history, the variety, the differences of life of Indigenous peoples in Canada, that’s the bottom line,” Tailleur says.

“This course is an important piece of that necessary education.”

“There’s a really long road ahead of us to reconcile everything that’s happened to Indigenous people in Canada,” adds Adam Van der Zwan, a second-year Master of Journalism student in the Stories North course. “You can’t be a journalist in Canada today and not come across at least one story involving Indigenous people and, when you come across that story, you need to know how to report on that sensitively and appropriately.”

Tailleur also spoke to the value of hands-on learning.

On the grounds of the former Chooutla Residential School in Carcross, Yukon, stewards, community members and outreach workers now seek to find ways to make a place of pain into a site where the past will be remembered and where the community can also come together.

“Imagine you are learning about residential schools in a claustrophobic classroom with grey walls and desktop computers in front of you,” she says. “Now imagine you are standing on the ruins of a former residential school and you’re hearing about the history of that. That’s the experience the Stories North students had when they went to visit the former Chooutla Residential School. That is powerful, that is going to stay with them.”

For Raisa Patel, a second-year Master of Journalism student who took part in the course, one of the highlights was the time and space she was given to interact with community members who were telling their stories.

“Sometimes that takes hours, it doesn’t take a 10-minute phone conversation,” she says. “It’s all about having that patience and taking that time to understand the diversity and complexity of the North. I was so overwhelmed by the community’s generosity.”

In the near future, Holmes hopes to expand the course to other Journalism schools in Canada, as well as in communities across the North.

“When it comes to working with Indigenous communities, we need to understand it takes an investment of time,” Holmes says. “It’s really an exercise in building trust in communities and it’s not going to happen overnight.”

Monday, October 15, 2018 in Experiential Learning, Indigenous, Journalism and Communication

Share: Twitter, Facebook