Lead image by elizparodi / iStock

By Laura Madokoro

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

Laura Madokoro is an associate professor of history at Carleton University.

Sanctuary cities in the United States, which limit local cooperation with federal immigration enforcement, have drawn the ire of President Donald Trump during both of his administrations.

Border czar Tom Homan said in July 2025 that the Trump administration would target sanctuary cities across the country and “flood the zone” with agents from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to pursue deportation goals.

I am a historian of migration. I have found that the concept of sanctuary takes many forms, from gestures of kindness and advocacy to more formal approaches such as churches protecting migrants at risk of arrest and deportation.

In the U.S., sanctuary city policies have historically been designed to support undocumented immigrants and refugees, especially those facing deportation. Ordinances based on these policies are often used by local authorities to signal the need for substantive immigration reform.

New public sanctuary policies

Today’s sanctuary practices, and the federal targeting of sanctuary cities, are largely the result of the way sanctuary took shape across the U.S. in the 1980s.

During this period, churches, city officials and activists assisted migrants fleeing the violent conditions created by U.S. proxy wars in El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala.

In the early 1980s, migrants arriving in the U.S. confronted restrictive asylum processes. To a large extent, this was the result of the Reagan administration’s refusal to acknowledge the extent of human rights violations perpetrated by U.S.-supported regimes in Central America.

In 1984, the federal government approved less than 3% of U.S. asylum claims by applicants who had fled El Salvador and Guatemala. By comparison, asylum claims were approved for over 30% – and in some cases, 60% – of refugees from Iran, Afghanistan and Poland.

In response, U.S. activists and church and city leaders began to advocate on behalf of refugees from Central America. They sought to effect change at home and abroad, eventually coalescing into what became known as the Sanctuary Movement.

This largely decentralized coalition focused on protecting refugees by providing safe housing, often in churches, and advocating for their right to seek asylum. And they engaged in public outreach to raise awareness about the conditions in Central America and the U.S. government’s role in conflicts there.

The goal was to change U.S. policy. As one sanctuary worker in Texas said in 1985, according to accounts compiled at the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin: “Sanctuary offers a way, by which folks can, number one, be safe from the fear of death, and, number two, speak out as to what is really going on in Central America.”

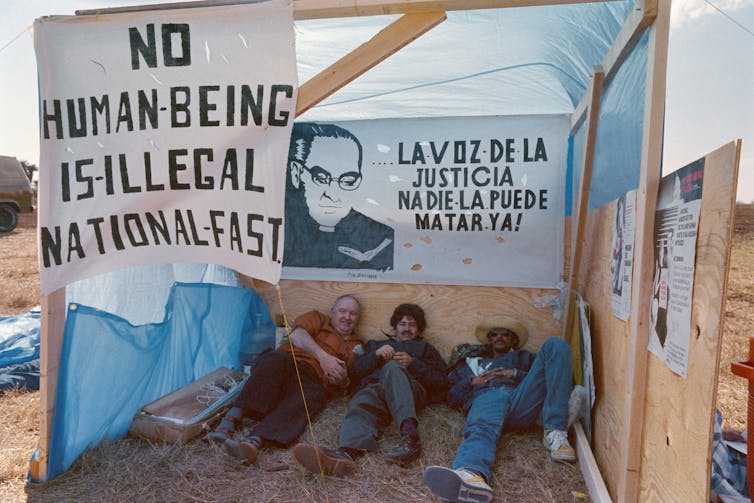

Walt Frerck/AFP/Getty Images

The Sanctuary Movement also led to organized visits to the U.S.-Mexico border to witness the ways in which migrants were being treated by U.S. immigration officials. In Texas between 1983 and 1985, for instance, people were invited to document the activities of immigration officials at Port Isabel Detention Center.

Members of the Sanctuary Movement also shared some of the horrors they learned about from missionaries and refugees arriving from Central America, according to accounts in the Benson Latin American Collection.

As a member of the Rio Grande Border Witness group conveyed, according to records preserved in the Benson Latin American Collection, there were repeated stories out of Central America “of women being raped and stabbed” and “of fathers being murdered in front of their families.”

As awareness about violence in Central America increased, more people and congregations in the U.S. became involved in the Sanctuary Movement. At its peak in 1986, the movement included 300 churches that endorsed sanctuary for Central American migrants and the principles underpinning the Sanctuary Movement.

Public and symbolic

It was during this peak that U.S. cities first began making sanctuary declarations and later passed binding ordinances.

In 1985, Berkeley, California, which had previously declared itself a sanctuary city for conscientious objectors to the Vietnam War, made one of the first sanctuary city declarations on behalf of refugees from Central America. Its resolution reaffirmed the city’s “support for the principle of sanctuary and for those groups which engage in this time-honored tradition of humanitarian assistance.”

City officials said that no city employee would “violate the established sanctuaries by assisting in investigations, public or clandestine, by engaging in or assisting with arrests for alleged violation of immigration laws by the refugees in the sanctuaries or by those offering sanctuary.”

AP Photo/Olga Fedorova

Cities such as San Francisco and Santa Fe, New Mexico, followed with declarations or binding ordinances. These initiatives were often specifically crafted for migrants from Central America and contained critiques of U.S. foreign policy and asylum policy.

A 1989 San Francisco ordinance, which is still in effect, was inspired by the notion that the U.S. had special obligations to the citizens of El Salvador and Guatemala because of its role in the conflicts there.

There was powerful rhetoric and symbolism in the sanctuary city resolutions passed in the 1980s. This holds true for the present, as sanctuary declarations and policies have become increasingly polarizing in today’s political climate.

Moreover, as I note in my own work, public acts of sanctuary can come at a cost, often at the expense of the very people they are meant to help. In an effort to raise public awareness and sympathy, those in need of refuge often have their most harrowing moments laid bare for public consumption.

The Sanctuary Movement that began in the 1980s, in part to protest U.S. support for repressive governments, has endured for more than 40 years as an expression of concern for and solidarity with immigrants who come to the U.S.

The question now is how the movement will evolve in the face of the Trump administration’s threats.

Some sanctuary city leaders, such as Boston Mayor Michelle Wu, have responded by pointing to the value of policies that foster community trust and help keep all residents safe. How other leaders and communities respond remains to be seen.

![]()

Friday, August 15, 2025 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook