By Dan Rubinstein

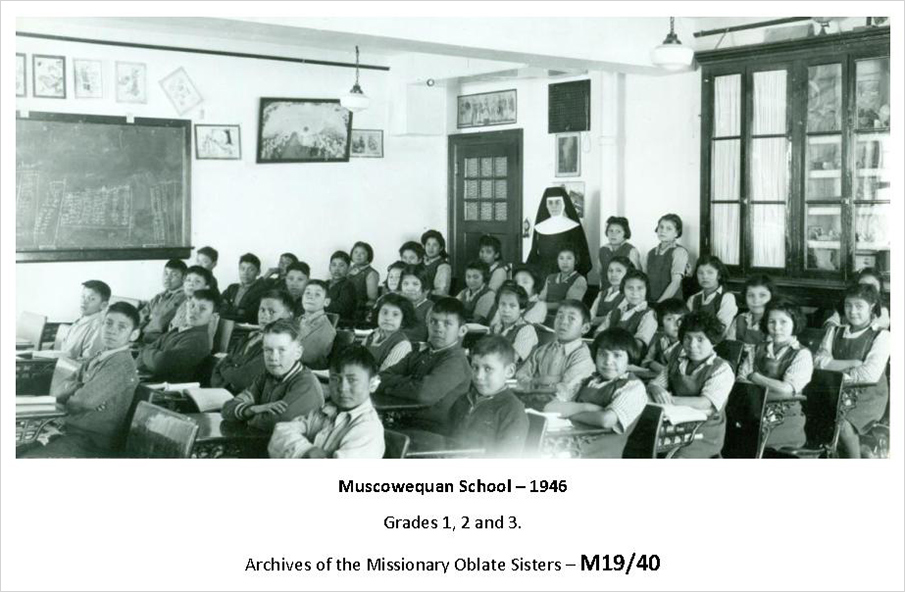

The following story was written before the discovery of 215 Indigenous children’s remains at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School on Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc land.

The colossal, three-storey red brick building is surrounded by farm fields and prairie wetlands, overshadowing everything else on the outskirts of the Muskowekwan First Nation, a Saulteaux community in southeastern Saskatchewan.

A long, elm-lined driveway leads to the front door of the Collegiate Gothic structure, which features ornamental stone trims on the façade and is the last intact residential school standing in the province.

Constructed in 1930 to replace an 1880s building that burned to the ground, it stopped operating as a government-run school in 1982, becoming a multi-purpose facility with a daycare, classrooms, a restaurant and transitional housing for youth, then closed for good in 1997.

“Horrific things happened inside,” says Muskowekwan Band Councillor Cynthia Desjarlais, who lived across a field from the school when she was a student there in the early 1980s.

“We were young, but still we knew.”

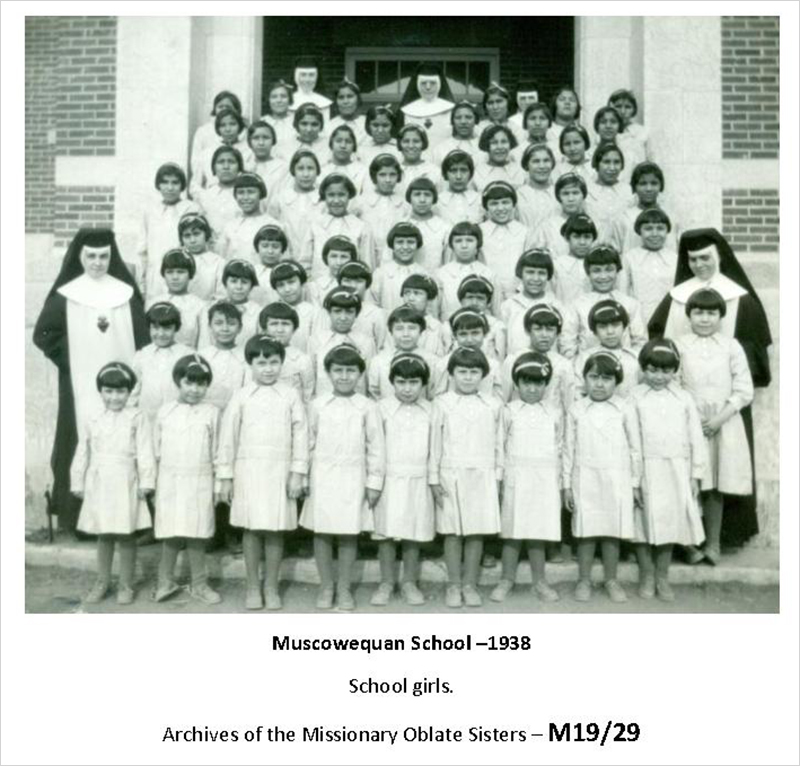

Desjarlais, whose mother had also attended the school and worked there as a janitor while Cynthia was a student, recalls a boy in Grade 7 who hanged himself. Several dozen children were buried in unmarked graves on the property, among more than 3,000 students who died while attending residential schools across Canada, and she can name about 30 former classmates who are already dead, including one of her brothers—victims of physical, psychological and sexual abuse suffered at the school and the intergenerational trauma that reverberates throughout the community.

Yet when the federal government offered money to tear down the building, all but four of the 339 Elders, residential school survivors and community members gathered in Muskowekwan voted to keep it standing.

“It’s proof to future generations and to the rest of the country that these schools existed,” says Desjarlais, “so this history is not swept under the rug. If people don’t see things, they tend to forget them.”

Now, in collaboration with students and faculty from Carleton University’s Architecture program and the National Trust for Canada, the Muskowekwan First Nation is planning to create a training and developing centre, museum, archive and memorial at the site—to transform the school’s tragic legacy into something hopeful.

“It’s important to restore it, so the school can serve as a reminder,” says Desjarlais.

“Our Elders want to see it used for something good. For the children who never made it home.”

School Becomes Focus of Course

In 2018, the National Trust put the Muskowekwan Residential School on its list of the Top 10 Endangered Places in Canada. National Trust Executive Director Natalie Bull and a pair of faculty members from Carleton’s Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism—Adjunct Prof. Lyette Fortin and Prof. Stephen Fai, director of the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) — visited Muskowekan in November 2018.

Following an inspirational meeting with Elders and other community members, Fortin was determined to make the deteriorating residential school the focus of a studio course in the architecture program’s Conservation and Sustainability stream, and Fai hoped to use his lab to make a detailed 3D model.

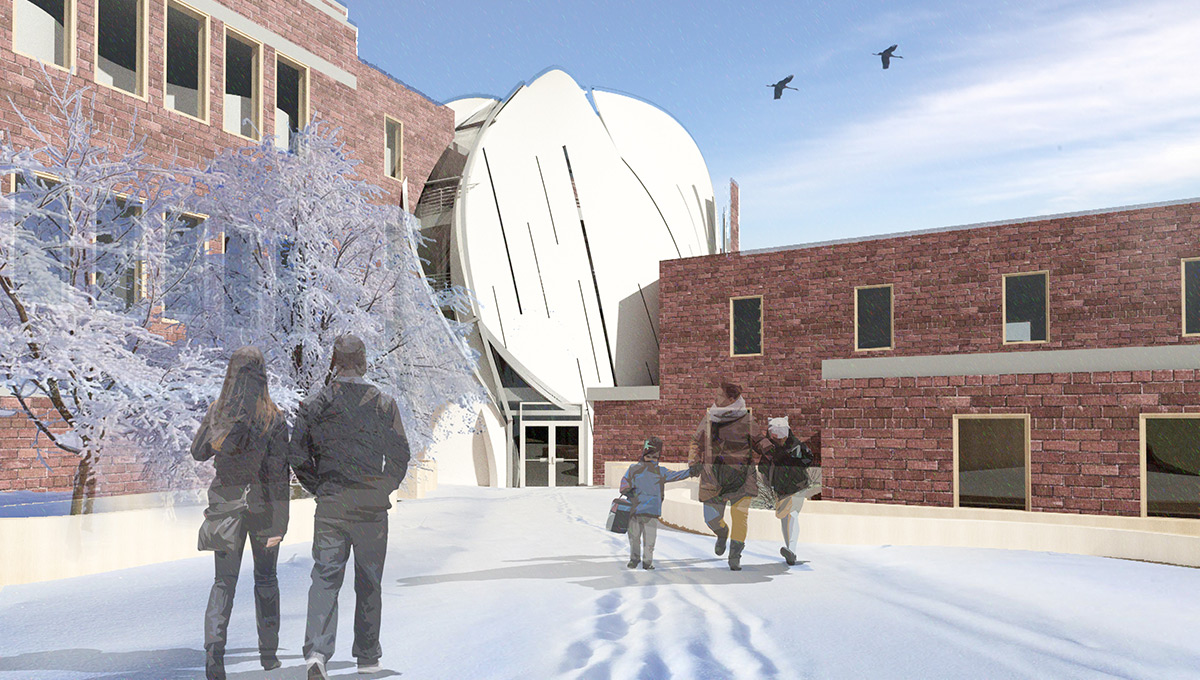

From “MOOKA’AM – ‘A rising sun.’ A new beginning.” (By: Teagan Hyndman and Arkoun Merchant) – one of nine designs produced by students in Carleton’s architectural studies program.

“How do you take a colonial Indian Act-era building and repurpose it into a place that reflects Indigenous values and culture?” asks Jim Mountain, a Carleton adjunct professor who inherited the January 2019 studio course from Fortin.

“We spoke with Cynthia and others members of the Muskowekwan First Nation,” says Mountain, “who told us the building was a dark place, both physically and with generations of bad memories, and that we needed to let light in. There’s a lot of hurt, but the community doesn’t want those stories to disappear.”

Two months into the studio course, Desjarlais and Muskowekwan Chief Reg Bellerose came to Ottawa for a meeting with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) National Chief Perry Bellegarde. They set up a presentation at AFN headquarters and met with the Carleton professors and students, and a partnership with the university took root.

Front Row – Lauren Liebe, Khadija Waheed, Spencer Lapko, Hassan Hannawi, Vanessa De Alexandris, Hope Good, Arkoun Merchant, Patrick Bustin | Back Row – Kseniia Beliaeva ,Claire Bodrug, Merissa Lompart, Carlee Wale, Teagan Hyndman, Kaleigh Mackay, Panchi Galvan, Danica Mitric

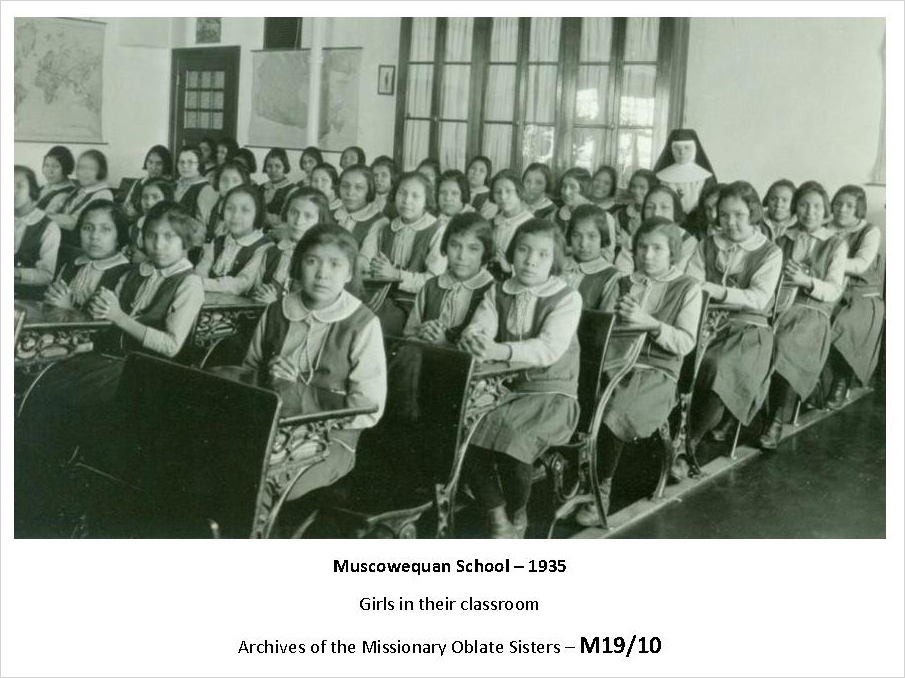

The students researched the history of the school, studied the surrounding landscape and climate, and compiled archival images and copies of the original architectural drawings.

By the end of the term, they had come up with nine designs for the Muskowekwan school site based on Indigenous values they had been mentored on by the Muskowekwan First Nation. The design concepts suggested, among other changes, much larger windows, more curvilinear elements, better flow between and flexibility within rooms, and a main entrance that no longer looked south but instead faced east, toward the sunrise.

Designs Bolster Bid for Historic Site Status

“It was the most difficult and emotional project I’ve ever worked on,” says Lauren Liebe, one of the students.

“We wanted to put our hearts into it and make something meaningful.”

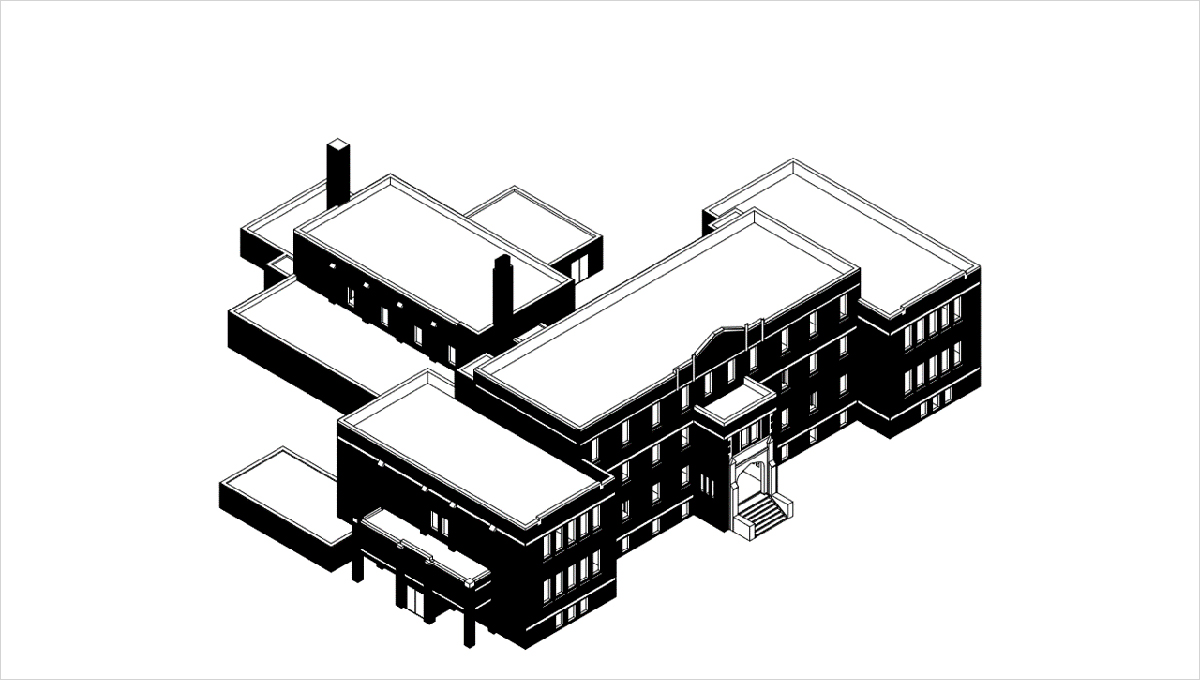

A couple months after the class, Liebe went to Muskowekwan to give the designs and supporting material to Desjarlais and her fellow councillors. Fai and a small crew from CIMS were also there, laser scanning and taking photos of the school for their 3D modelling.

Model by Lauren Liebe

The student designs and modelling could inform ultimate plans for the site and they will bolster a bid for National Historic Site status, which has already been submitted to Parks Canada.

“As a kid growing up in Saskatchewan, I was shocked that residential schools were part of our history,” says Liebe.

“As devastating as the stories are, I’ll never really know what children there experienced. Now the community has an opportunity to reclaim the building and I feel privileged to have been part of this. It’s something I’ll think about forever.”

The Muskowekwan Residential School already has new life.

School groups and people from nearby cities and towns visit to learn more about what happened inside the building and the impact of those experiences on the long road toward reconciliation.

“Like other historic sites, people come here to understand the past,” says Desjarlais, explaining that the proposed training centre will help community members, while the museum, archive and memorial will have both ceremonial and educational roles.

And this summer, just down the road from the school, several log homes will be raised for a new traditional, land-based healing and wellness centre.

“Despite everything that happened to us, we lived through it and survived,” says Desjarlais.

“Now we have to help our people get better in any way we can.”

Tuesday, June 15, 2021 in Architecture, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook