Lead image by vkyryl / iStockPhoto

By Ty Burke

A bird of prey swoops silently through the night, and grasps a catch in its talons. Owls are not the fastest fliers, but the shape of their wings enables them to glide with barely any sound. And the evolutionary advantage conveyed by nearly silent flight has allowed these highly efficient predators to thrive for tens of millions of years.

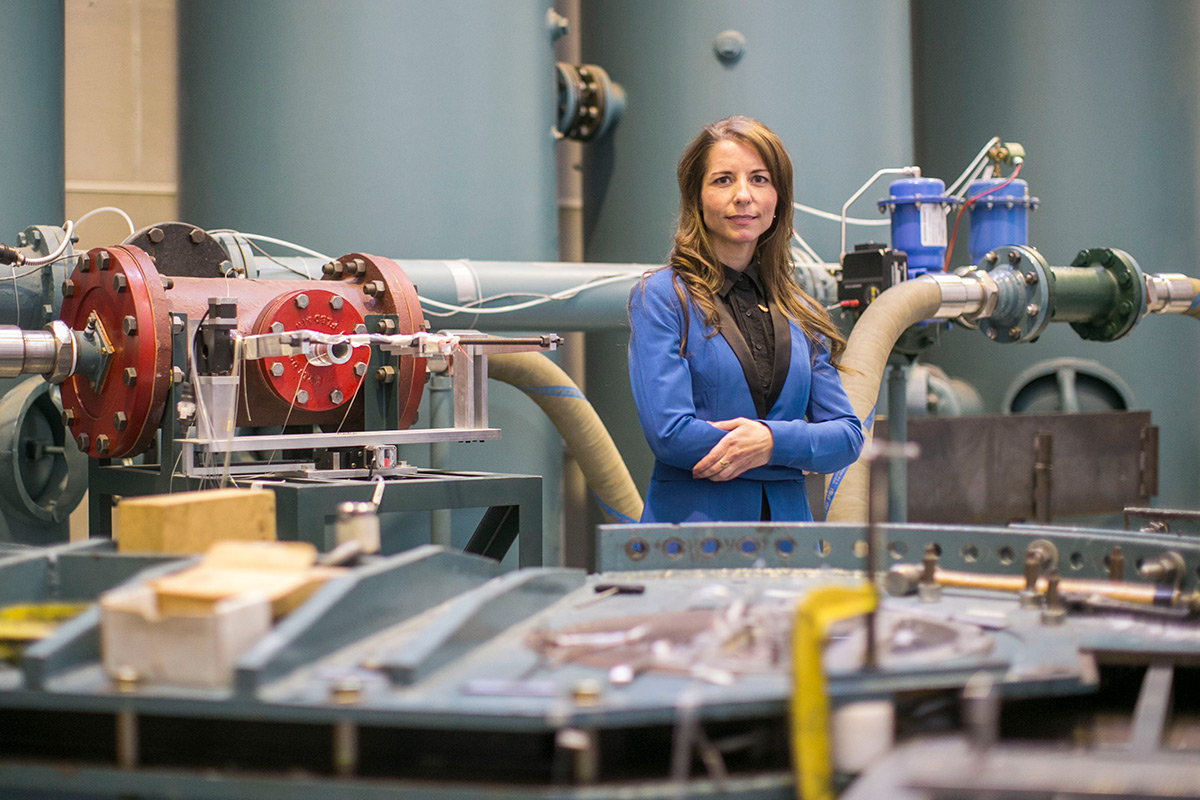

For Carleton University Prof. Joana Rocha and her research team, the owl is a kind of inspiration. The professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering specializes in aeroacoustics, and is exploring how the aircraft of the future could be (nearly) as silent as an owl in flight.

Prof. Joana Rocha

“The flow of air around an aircraft structure or body often creates noise,” says Rocha.

“But when a surface is optimized for its application, it can produce lower levels of noise. And we can potentially make aircraft much quieter.”

Aircraft noise affects how passengers perceive the quality of a flight, and quieter aircraft reduce disturbances to the communities where airports are located. With higher levels of air travel, this noise is increasingly a concern. Some cities have instituted noise quotas that permit a limited amount of exposure each day. And in the future, noise could become an even greater concern, as drones and other air transport vehicles fill our skies.

“High levels of noise have health effects too,” says Rocha. “Noise associated with cardiovascular disease, hearing loss, hypertension, and sleep disorders. In addition, noise is often the result of inefficiencies, representing a form of loss of energy in the overall system.”

But studying aircraft noise presents some unique challenges. Most wind tunnels are noisy, and that’s OK for many of the applications that they are used for. Measurements related aerodynamics or temperature are unaffected by background noise. But to study noise itself, wind tunnels need to be retrofitted or even redesigned, so that they are quieter.

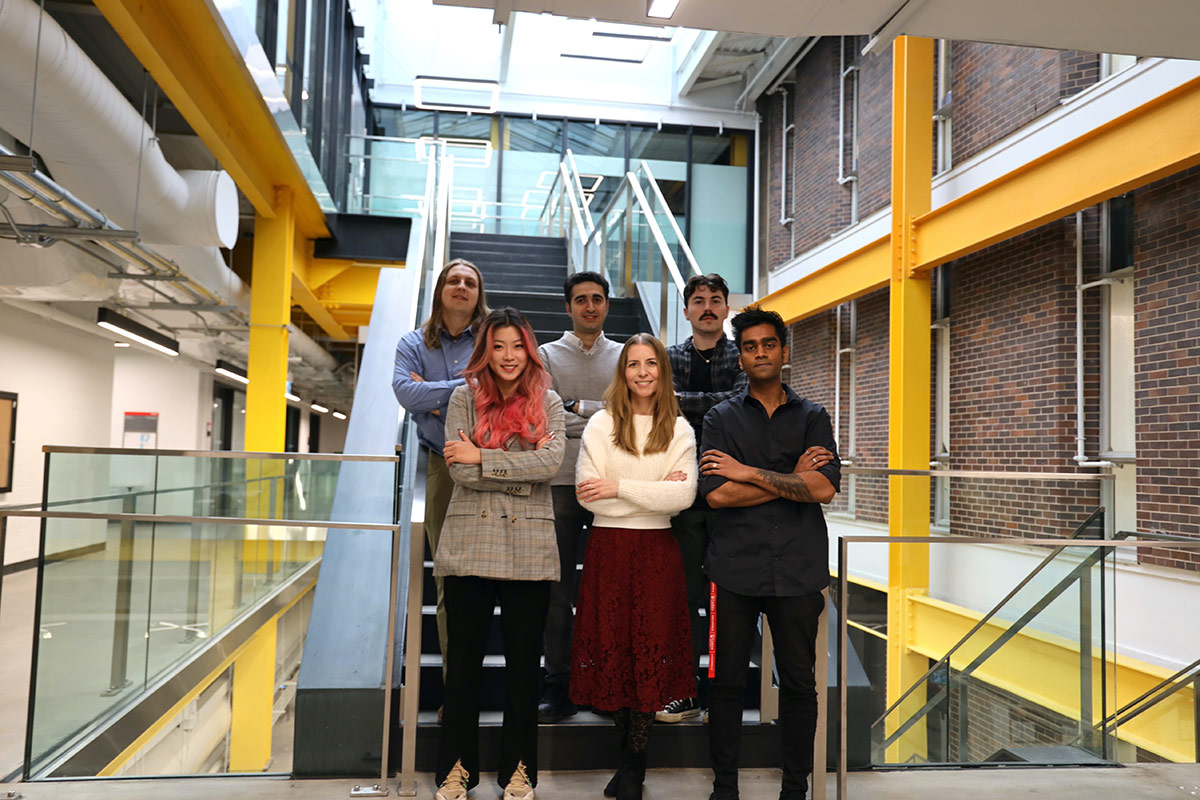

Prof. Rocha with her students (Photo: Brenna Mackay)

“Our microphones are small devices, mounted in the wind tunnel or on the models we are testing,” says Rocha.

“We need to eliminate other sources of noise to study flow-induced noise. The wind tunnels should be as silent as possible.”

Rocha began developing aircraft noise prediction models during her PhD research at the University of Victoria. At the time, she was taking a lot of long flights, and became interested in the noise of air flowing around the structure of the aircraft. The models she developed during her PhD led to a visiting researcher position at the NASA Langley Research Centre and National Institute of Aerospace in Virginia.

As a graduate student, Rocha supported aerospace education by volunteering to speak with undergrads about STEM education. And since coming to Carleton in 2012, she has continued to share her passion for aviation with students and colleagues alike. She established the AeroAcoustics Research Laboratory, has taken on leadership roles in the Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering, and supported women in STEM initiatives through mentoring and volunteering.

Rocha (middle) after being recognized with an Elsie MacGill Award (Photo: Ken Lin)

Rocha’s contributions to aviation and aerospace have been recognized with an Elsie MacGill Award. MacGill was the first woman in the world to work as an aircraft designer, and each year, the Northern Lights Aero Foundation honours the achievements of women in seven different categories. In 2023, Rocha won the Elsie Award for Education, which recognizes not only excellence in teaching, but also contributions as a mentor and role model.

“My interest in aerospace started early. My family and I attended an airshow — as a young girl, it captured my interest and imagination. It was a big event, with many aircraft — big ones, small ones, noisy ones! I wanted to understand how such a heavy machine could fly,” says Rocha.

“I enjoyed school, and loved topics such as math and sciences. I had a passion, was a successful student, and had good mentors along the way. So, I also wanted to give back. I feel that it is part of the role of a professor, as I recognize how important good mentors can be.”

Monday, November 27, 2023 in Faculty of Engineering and Design, Innovation, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook