By Lisa Gregoire

Photos by Mike Pinder

Forty years ago, Canadians helped more than 120,000 refugees settle in Canada after brutal communist regimes took over in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

The refugees came in waves, from 1975 to 1990, in rickety, undersized boats with little or no navigation, and over land, across rivers and through mountain passes. They took only what they could carry—clothes, bits of food, children, unborn babies and memories.

Canadian church groups, municipalities, organizations and individuals opened their arms to them, accessing sponsorship programs created specifically by the Canadian government to respond to the crisis.

Not since the settlement of displaced persons following the Second World War had Canada given safe haven to so many people at once, and never before to a group of people so culturally, ethnically and linguistically different from the Canadian bilingual mainstream.

In 1986, the United Nations recognized the extraordinary role Canada played in resolving the South East Asian refugee crisis by giving “the people of Canada” the Nansen Refugee Award, the highest award for helping refugees. It was the first time it had ever been given to a country’s entire population.

Preserving Memories of Mass Migration

Decades passed and those desperate people who came to Canada as adults and children went to school, found jobs, married, bought houses, raised families and became loyal, grateful, contributing Canadians. And as time passed, memories of that mass migration faded into Canadian history.

That was until Dau-Thi Huynh and Minh Nguyen of the Vietnamese Canadian Federation (VCF) contacted Colleen Lundy, a professor emeritus in the School of Social Work at Carleton University, in 2015. They told Lundy they wanted to find a way to preserve that era in Canadian history so it would never be forgotten.

Colleen Lundy, a professor emeritus in the School of Social Work.

“I got on board very quickly because they were so excited,” Lundy said recently.

“They were very well organized and seemed to just need a partner within an institution who could apply for funding.”

Several years later, with support from Canadian Heritage, numerous partners such as the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 and the Canadian Museum of History, and many dedicated staff and volunteers, the Hearts of Freedom project is poised to become a powerful vehicle for remembering.

Originally, the VCF wanted to build a museum, but as discussions progressed and others joined the team—Peter Duschinsky, a retired immigration foreign service officer; Mike Molloy, senior co-ordinator of the Indochinese Refugee Task Force from 1979 to 1980; and Stephanie Stobbe, an associate professor at Menno Simons College, University of Winnipeg—the project changed.

The scope was broadened to include the Cambodian and Laotian communities and focus turned to capturing the lived experiences of South East Asian refugees through videotaped interviews. With a budget of roughly $350,000, the team hired and trained three interview teams, one for each of the three countries involved, and set about interviewing voluntary participants in Ottawa, Gatineau and Montreal.

Human Strength and Resilience

The stories that came back were a testament to human strength and resilience.

One Cambodian man was interviewed with his daughter. He told of how he fled the Khmer Rouge’s murderous regime on foot through mountains with his pregnant wife. She had the baby en route, he said, and both mother and baby were carried in a hammock to a refugee camp in Thailand. After telling the story, the man pointed to his daughter and said: “That’s her.” They named her Samnang, which means “lucky.”

One man told of jumping into a crowded little boat at night with nothing but the North Star to help navigate. Another man talked about how the boat he was in was commandeered by pirates who, upon seeing how little the occupants had, cooked the rag-tag group a meal before leaving.

Allan Moscovitch, a professor emeritus in the School of Social Work.

Members of the interview teams are Cambodian, Vietnamese and Laotian Canadians. For them, the stories hit home.

“What these folks say is that often it was their parents who were the refugees, and they’ve never heard those stories so it’s gratifying for them,” said Allan Moscovitch, also professor emeritus at Carleton’s School of Social Work and a member of the Hearts of Freedom project team.

“They feel like this is their opportunity to do something for their community, by helping to capture these stories. I’ve been struck by their enormous commitment.”

Lundy said the stories have a broader message too, at a time when racism and xenophobia rule immigration policies south of the border and unstable regimes, along with climate change, increasingly make places around the world unlivable.

“Newcomers are really so resilient. They begin working and they become full participants in our society. Right now, there’s a big backlash against refugees. The U.S. is terrible and Canada can easily slip into that,” she said.

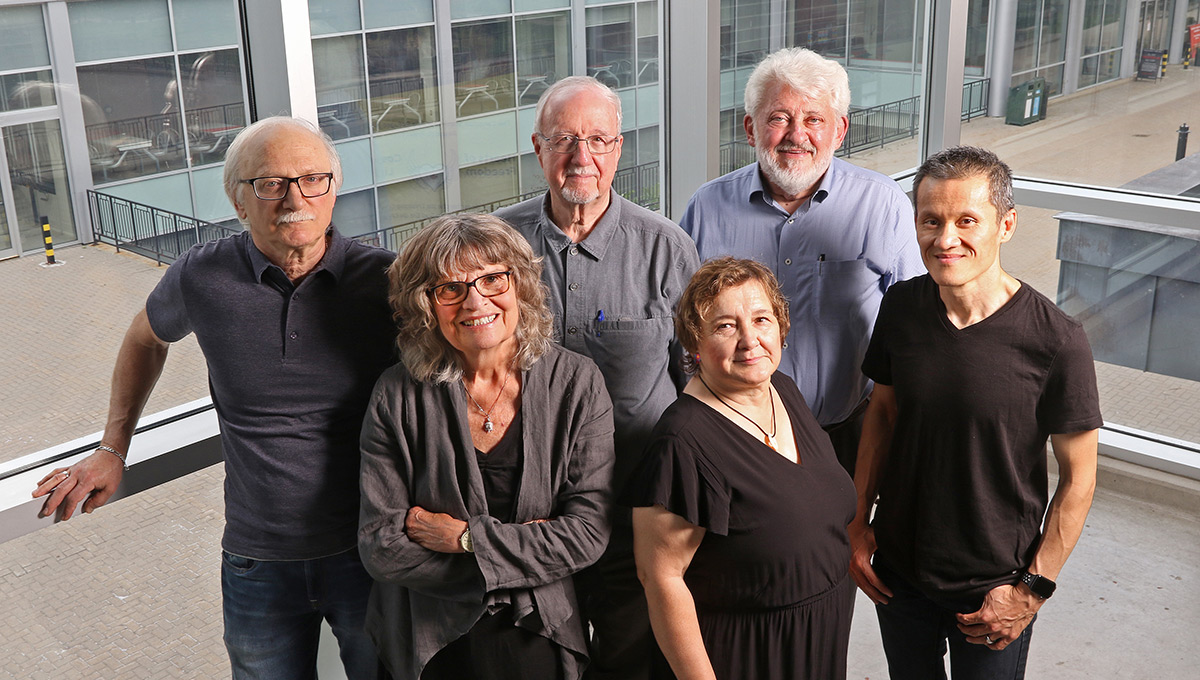

From left to right Allan Moscovitch, Colleen Lundy, Mike Molloy, Ginette Thomas (Project Coordinator), Peter Duschinsky, Mondy Lim (Media Coordinator)

The Role of the Refugee in Society

“The message,” Moscovitch continued, “is that refugees are not a burden. On the contrary, they contribute enormously to society.”

A total of 66 interviews have been completed and teams are now heading to Toronto, home to the largest number of Vietnamese Canadians, to interview participants there. They are also interviewing civil servants, sponsors and others to round out the story from the Canadian perspective.

A private donor has agreed to fund interviews in Winnipeg so the original plan of 110 interviews will likely increase to 126. The team continues to seek more funding to conduct interviews in Alberta and British Columbia.

Once the interviews are completed and transcribed, the project team plans to make a documentary film, publish a book and develop curriculum materials for public schools and universities. Carleton’s Archives and Research Collections has agreed to preserve the video record and other materials generated from the project.

To learn more about Hearts of Freedom, or to view the first round of interviews, go to heartsoffreedom.org.

Monday, September 23, 2019 in Community, Faculty of Public and Global Affairs, Social Work

Share: Twitter, Facebook