By Tyrone Burke

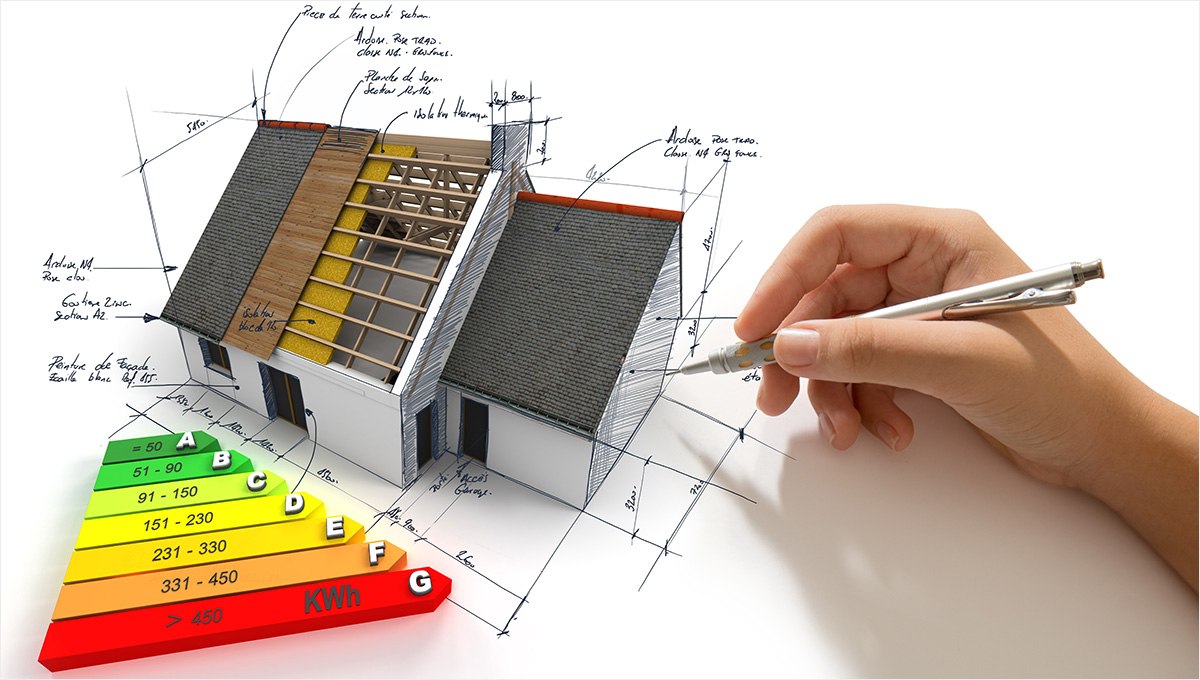

Canada has a housing emergency, and the problem is multidimensional. There is a crisis of affordability that is fuelling homelessness. There is a lack of accessible housing for our aging population. And then there is the environmental impact. Buildings account for 22 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions—and more than double that when emissions associated with transportation between buildings is factored in.

Liam O’Brien is seeking to address these challenges. A professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the principal investigator in Carleton University’s Human-Building Interaction Lab, O’Brien’s research focuses on occupant comfort, resilience and energy use. But he views these challenges through an engineering lens. To ensure he has a holistic understanding, he collaborates with researchers from other fields.

Professor and Human-Building Interaction Lab Principal Investigator Liam O’Brien

“Buildings are complex, with lots of interactions between systems, humans and the environment. During the design process you can fix all sorts of parameters, like insulation, lighting and heating and cooling technology. But the real test comes when you bring in occupants,” says O’Brien.

“That’s when personal preferences enter the picture, and when the gaps between design intent and occupant preferences are revealed. These gaps are how I became interested in better incorporating occupant needs into the design process, in bringing more people to the table to understand their needs, preferences and constraints. It is important to include lots of voices to consider accessibility, affordability and comfort.”

Collaborating on Complex Needs

Carleton is ripe for this type of collaboration, with researchers that specialize in heating and cooling systems, building information modelling, computer simulation, energy efficiency, architecture, aging, homelessness and the social determinants of health.

One thing about Canada’s housing crisis is clear: to fix it, we will need more multi-unit buildings. Historically, building research in Canada has focused on single-family homes. These have been central to the Canadian dream, but that dream is changing. Multi-unit dwellings could help house the homeless, allow seniors to age with dignity, improve social connectedness, create more walkable communities and make housing more affordable.

O’Brien’s research centres on this gap—understanding how larger buildings can meet the complex needs of their users. A collaboration with researchers from the Carleton Immersive Media Studio and Carleton’s Department of Systems and Computer Engineering has afforded the university a deeper understanding of how its own buildings are actually used, so their energy efficiency can be maximized.

Prof. O’Brien with Carleton Immersive Media Studio director Stephen Fai and lead SUSTAIN Project researcher Gabriel Wainer (Photo: Luther Caverly)

In a project funded through NSERC, O’Brien worked with Architecture Prof. Stephen Fai and Computer Science Prof. Gabriel Wainer on the Sensor-based Unified Simulation Techniques for Advanced In-Building Networks (SUSTAIN) project to make digital copies of campus buildings and monitor use patterns through a network of sensors. This helped building managers identify where energy efficiency gains could be made. And while buildings on campus serve many different purposes, these principles can be applied to residential buildings. They can be scaled to make a city—or even a whole planet—a healthier place to live.

“Buildings affect their local ecosystems, like how walkable a neighbourhood is and how healthy its residents are,” says O’Brien.

“But they also have a global effect, through things like their greenhouse gas emissions. You really need a team to work on buildings. I specialize in occupant behaviour and comfort, but I really benefit from collaborative opportunities with people in other fields.”

Household Emissions and Lifestyle Changes

The effects of occupant behaviour aren’t always intuitive. During the pandemic, O’Brien shifted his focus to changes in building occupancy patterns caused by office workers’ sudden move to a work-from-home model.

For many, the morning commute was reduced to the length of a hallway, or even less. The accompanying reduction in vehicle use seems like it would reduce emissions, but things are not quite this simple. Buildings are a major source of emissions, and thousands of people working from home increased their energy use.

“Household energy use did some unexpected things during the pandemic,” says O’Brien.

“Office buildings didn’t use much less energy. These buildings were not designed to adapt to low levels of occupancy, so their energy use was almost the same.

“And there was also an outward movement from cities to surrounding areas. When people don’t need to come to the office every day, they can justify living farther from the places they work. In many cases, that drives up a household’s transportation needs.

“If you move to rural Ottawa, suddenly you’ll likely be reliant on one car per adult. Whereas before, you might have been able to rely on transit and maybe just one car. This new lifestyle could increase a household’s emissions by an order of magnitude.”

Monday, November 14, 2022 in Environment and Sustainability, Faculty of Engineering and Design, Innovation, Research

Share: Twitter, Facebook