By Ummni Khan

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

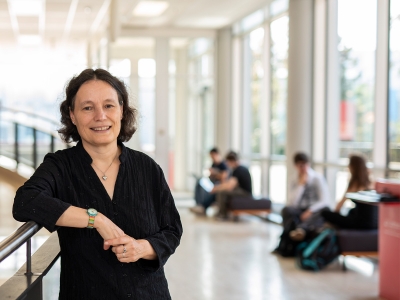

Ummni Khan is an associate professor of law and legal studies at Carleton University.

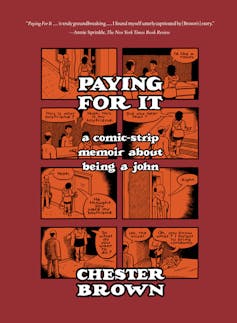

The film Paying For It, Sook-Yin Lee’s live-action adaptation of cartoonist Chester Brown’s 2011 graphic memoir, reveals unexpected overlaps between paid sexual encounters and romantic relationships.

Lee, a boundary-shattering artist working across film, music, acting and broadcast, has never shied away from taboo. With Paying For It, she takes on sex work, romance and the messy labour of chosen family by adapting her ex-lover’s memoir for the screen.

(Drawn & Quarterly)

In my 2019 article “Chester Brown and the Queerness of Johns,” I analyze Brown’s original book, which traces his pivot from monogamy with Lee to regularly seeing sex workers in the late 1990s.

Both a memoir and a manifesto, the book pairs accounts of paid sex with arguments for decriminalizing sex work, voiced through debates with friends and a detailed appendix. In my analysis, I frame Brown’s memoir as a queer intervention, one that disrupts heteronormative ideals of romantic relations, intimate exchanges and sexual propriety.

Lee’s cinematic version of Paying For It affirms Brown’s stance, but filters the story through her own perceptions and snapshots of her love life. In doing so, she traces how she and Brown reinvented their relationship, while portraying his encounters with sex workers with nuance and care.

Drawing on my research in sexuality — including scholarship on sex work, client surveillance and client regulation — I see the film as a defiant celebration of unconventional bonds between exes who remain best friends, and between clients and sex workers, where even purchased orgasms can carry moments of tenderness and mutual respect.

Radical relationship honesty

The film opens with Sonny (Lee’s fictional persona, played by Emily Lê) confessing to live-in boyfriend Chester (Daniel Beirne) that she’s falling in love with someone else.

Rather than erupting in rage or jealousy, Chester remains composed. Together, they choose to see what might come next. As Sonny begins seeing other people, Chester continues living in the house and becomes privy to her romantic sagas, from the steamy beginnings to the bitter blowouts. To the bewilderment of his friends, he remains content with the arrangement.

Eventually, Chester decides to pay for sex, a decision he shares with Sonny.

What emerges is a portrait of creative kinship where two people refuse the usual scripts and choose radical openness instead.

Unconventional bond

Decades after the events depicted in the film, Lee has described Brown as her “best friend” and “as family.”

Lee and Brown shape personal histories into overlapping narratives. That they’ve promoted the film together, and appeared in joint interviews and public discussions, suggests a sense of mutual trust at the heart of their collaboration.

Probing the meanings of sex and intimacy

Chester moves — and sometimes stumbles — through criminalized terrain, figuring out how to find sex workers, engage respectfully and follow the unspoken rules of the exchange. The film suggests sometimes it’s just sex for Chester, and at other times, the exchange carries an emotional connection for him.

With one sex worker, Chester shares his real name and gifts a book he wrote about Louis Riel.

Sociologist Elizabeth Bernstein has analyzed how sex workers are sometimes paid to offer their clients an erotic experience “premised upon the performance of authentic interpersonal connection.”

In the film, a potential for emotional reciprocity between Chester and a sex worker becomes evident. Without giving too much away, by the film’s end we see how a casual and transactional beginning transforms into something more enduring for both parties.

Risks in both romance and sex work

The film also highlights the risks running through both sex work and romance.

Sex workers face threats of abuse, arrest, disrespect and boundary violations. The film gestures to these realities in a scene following a police raid on a sex work venue.

But the film also shows Sonny’s relationships aren’t immune to danger either. One boyfriend’s rage nearly results in harm to her pet.

Just as navigating risk is part of both romance and sex work, so too is grappling with the social forces that shape desire. In one pointed exchange, Sonny calls out Chester for only paying young, conventionally attractive women. He counters by asking why she doesn’t date Asian men, forcing them both to confront their own biases.

Sex worker rights

While Paying For It is deeply personal, it is also unmistakably political, especially in its implicit advocacy for sex worker rights.

To navigate the ethical complexities of depicting sex work, Lee consulted with performer, activist and author Andrea Werhurn, who wrote a memoir about being a former escort; Werhurn stars in the film as the sex worker Denise.

Lee also interviewed Valerie Scott — one of the applicants who challenged Canada’s prostitution laws in the Bedford case.

The film presents sex work as legitimate labour, highlighting the skills and emotional intelligence it demands. At the same time, it underscores how sex workers remain vulnerable to police harassment, violence and social stigma.

Canada’s perverse laws on sex work

The marginalized status of sex work, as dramatized in the film, is shaped by a legal system structured by moralism and hypocrisy.

Set in the 1990s, Paying For It takes place at a time when Canada didn’t criminalize the sale of sex directly but prohibited nearly everything around it, including soliciting, working indoors and operating brothels.

These contradictions pushed the industry underground, exposing sex workers to abuse, police harassment, sting operations and heightened health risks, while often branding them with criminal records.

Sex work kept in the shadows

In 2013, the Supreme Court’s Bedford decision struck down these provisions, ruling that they violated sex workers’ constitutional rights, most importantly, the right to security of the person.

But the legal victory was short-lived. In 2014, the Conservative government introduced the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act, which criminalized the purchase of sexual services while ostensibly decriminalizing its sale.

In practice, the model keeps paid sex in the shadows, where workers face ongoing risks, limited negotiating power and barriers to reporting abuse or working in safer indoor settings. What’s being protected isn’t sex workers, but a puritanical social order.

This puritanical approach also underpins the newly criminalized status of clients. In my chapter “From Average Joe to Deviant John,” I trace how western attitudes toward men who pay for sex evolved from a “boys will be boys” tolerance to a framework that pathologizes and vilifies them.

Paying For It resists this framing. The film presents Chester as awkward but principled: a considerate client navigating desire in a criminalized and judgmental culture.

The price of choosing love freely

Paying For It offers an alternative kind of love story. It spotlights a relationship where former lovers honour the heart (their continued commitment to one another), the body (respecting each other’s sexual autonomy) and the mind (their willingness to question social norms).

In this way, the film redefines “paying for it” not as a burden but as a conscious and liberating investment in diverse forms of love and intimacy.

![]()

Thursday, May 22, 2025 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook