By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Justin Tang

Under an overhang of Carleton University’s Architecture Building, a pair of attractive wood-framed structures are taking shape. Small in size but ambitious in scope, they’re energy-efficient tiny houses embodying an amalgam of research, education and environmental stewardship. If you missed the story of the the Northern Nomad house, read it here.

Here’s the story of the Hobbit Van 2.

Three years ago, when Carleton architecture student and national team whitewater kayaker, Ben Hayward, took time off from his studies to train and compete in Europe in a bid to qualify for the 2016 Olympics in Rio, the cost of accommodation and travel was tough to manage on his amateur athlete’s budget.

So Hayward bought a used flatbed truck for just over $2,000 and, with $7,500 in materials and help from a Welsh mechanic friend, built a 72-square-foot wooden camper with a small wind turbine, solar panels and a round door at the back. He lived in the “Hobbit Van” for two years, driving from country to country to attend races, sleeping in parking lots.

Although he was Canada’s top ranked whitewater kayaker, Hayward didn’t earn a spot at Rio, but he’ll be returning to the Hobbit Van next year in an effort to make it to the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.

For now, he can found outside Carleton’s Architecture Building, putting the finishing touches on the Hobbit Van’s offspring — an energy-efficient solar-thermal tiny house that was born as a fourth-year design project and has morphed into the focus of a master’s degree he started this September.

“A lot of the design intent is to try to make it feel as big as possible,” Hayward said outside the 180-square-foot house on a late August morning as he peeled back a tarp to see if the previous night’s heavy rain had seeped beneath recently installed flooring. “I’m trying to compete with a bachelor condo, rather than with a recreational vehicle.

“I don’t want it to feel like camping. I want it to feel like a home.”

As municipalities across North America reexamine zoning regulations to make allowances for infill housing that increases residential density and helps address climate change, tiny houses are starting to attract more attention. They’re receiving more and more coverage on TV and in print and online media.

Larger Houses, Smaller Families

One of the challenges facing the tiny house movement is convincing people that they don’t need giant floorplans. The size of the average new build in the United States in 2015 was nearly 2,700 square feet — more than 1,000 square feet larger than it was in 1973, even though the size of the average family has dropped from three to 2.5 over the same span.

Collectively, our homes are taking up more urban space. All this development reduces green space, which increases the temperature of our cities, hinders storm water management, reduces the amount of carbon-sink vegetation, and can have a negative impact on our physical and psychological health.

We’re also burning a lot more fossil fuels to heat, cool and power all of the appliances and gadgets scattered around our sprawling houses.

But if designers and architects can create aesthetically pleasing and energy-efficient homes that people see as “desirable” rather than a “compromise,” says Hayward, the pendulum could start to swing back.

“There’s something really natural about being in a tiny house,” he says, thinking about his time in the Hobbit Van, which is the subject of a YouTube video that has generated more than 900,000 views. “Because everything you need is within reach.”

Scaling Technology for a Tiny House

Hayward began designing his tiny house as part of a manufactured housing studio course taught by Architecture Prof. Sheryl Boyle. A class visit to Carleton’s Urbandale Centre for Home Energy Research — a.k.a. the solar-thermal house on campus — inspired him to “think about scaling that technology for a tiny house,” says Boyle.

“It was wonderful to see how a visit to built work can inspire further ideas,” she adds, “which is one of the reasons why that house was built in the first place.”

Hayward’s design went through several iterations, and in April he secured a $6,000 Carleton University Research Opportunity grant from the Discovery Centre, which helped him start to build.

“Ben’s progress has been wonderful to watch over the summer,” says Boyle. “The project is very much a prototype, meaning that he is making innovative decisions each step of the way. This might at first appear to slow things down, compared to using standard building systems, but that’s what students are supposed to do — push the limits!

“Ben had incredible courage to undertake a project of this magnitude over the summer,” she continues.

“His experience as a high-performance athlete in a high-risk sport might have something to do with it.”

Eliminating Heat Loss

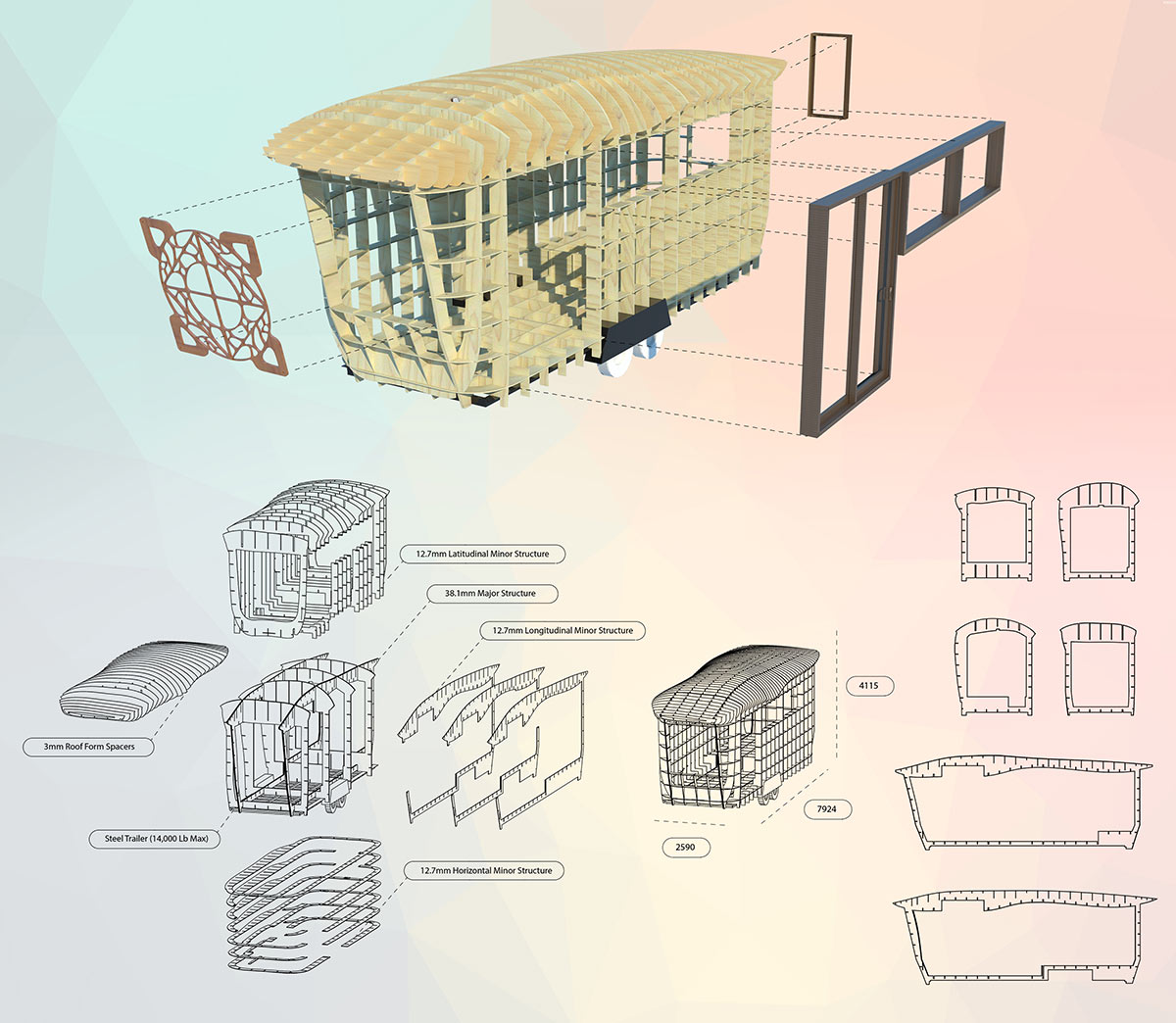

The distinctive curvy look of Hayward’s house is both attractive and functional. Because the walls get thicker as they rise, more insulation can be packed into the upper area, where heat loss typically occurs. The curves also eliminate hard-to-seal cracks and joints where heat is lost in conventional boxy houses.

Heating and hot water account for roughly 85 per cent of energy used in Canadian homes. Hayward is using a photovoltaic solar array that will feed electricity into two conventional domestic electric hot water tanks, which will be used as thermal batteries that supply the radiant in-floor heating system and hot water needs.

This relatively simple system, he argues, “is the most significant step towards making northern climate homes truly sustainable. By using photovoltaic panels as opposed to conventional hydronic solar thermal, it is significantly more economical and only pierces the building envelope with a single wire. This also poses the potential for a low-cost retrofit to existing buildings.”

To test the energy efficiency of his house over the winter, Hayward will have it towed to notoriously cold Edmonton, where his mother will live in it in her backyard while renting out the two units in her house. Having a full-time occupant in the tiny house will allow for constant monitoring of the sensors that track its performance, as well as provide a sense of what it’s like to actually live in the space.

Hayward’s tiny house is no barebones trailer. Its bespoke interior will be comprised of furniture and finishes that fulfill multiple purposes and convert smoothly — for instance, a bed that disappears into the ceiling, a large kitchen counter that hides all of the mechanics, a hinged side door that becomes a patio awning — and full-sized appliances like one would have in a conventional home.

Although Hayward is finishing all the carpentry by hand, he is using the architecture school’s robotic CNC (computer numerical control) system to digitally fabricate the structural frames of furniture and other elements that fit his unconventional curvy space perfectly. This digital approach allows the designs of individual pieces — and perhaps one day an entire tiny house — to be shared, replicated and reproduced.

“It’s like a giant puzzle,” says Hayward, “and you can only assemble it straight.

“It’s very valuable for architecture students to do some construction,” he adds. “You really get to know the materials and how they fit together.”

Sharing Tools and Ideas

Because Hayward’s tiny house is adjacent to the Northern Nomad project, he and the other students have been able to share tools and ideas as they work.

Like the student team building the Northern Nomad house, Hayward has also been able to secure donated material from an array of suppliers. The insulation, windows, roofing and radiant heating system were all free.

This serves as R&D for the suppliers, whose products are being used in innovative ways, generating data that can be used to gauge their performance.

Hayward plans to study the house’s energy efficiency as part of his master’s research. He also wants to look at urban planning and policies that pertain to tiny houses.

His mother can get away with living in this house in her backyard because it’s on wheels and can technically be considered a recreational vehicle. Zoning regulations in Edmonton — and across Canada — have to evolve if tiny houses are to achieve a greater foothold. And architects can be part of the push for change.

After all, the tiny house movement is about testing the limits of the spaces people need to live in, says Boyle.

“The tiny house is like a research lab,” she says, “and there is certainly room in design to reduce the footprint of construction, including physical square footage, energy use and materials use.

“I consider it to be like how the design of cars has transformed from ‘big and beautiful’ to the smaller cars of today and car-sharing concepts. Tiny homes open up research for the double or triple function of a space, and can test things that might be adapted at different scales later on. Ultimately, it’s about taking less space, less stuff, less materials and less energy to make beautiful places in which to dwell on the planet.”

Tuesday, October 24, 2017 in Architecture, Engineering, Environment and Sustainability

Share: Twitter, Facebook