By Warren Clarke and Nadine Powell

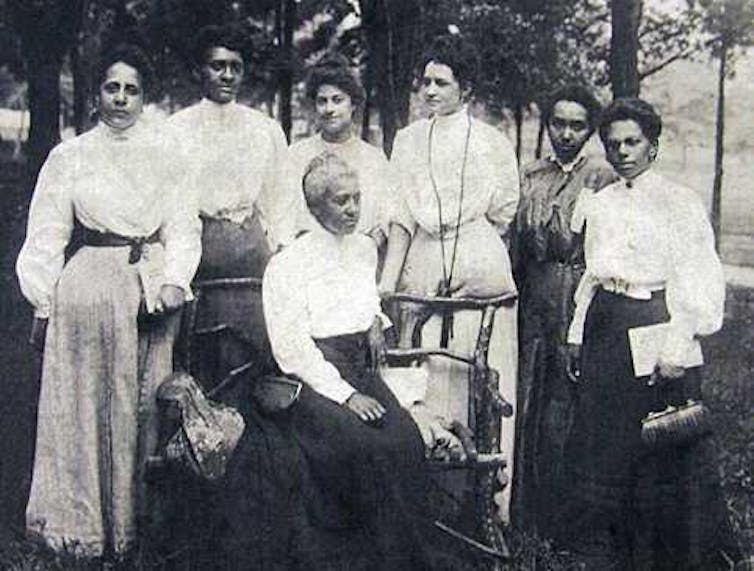

The first meeting of what would later become the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took place in 1905 in Fort Erie near Niagara Falls, Canada. Legendary thinkers such as W.E.B. Du Bois attended.

Although the social justice movement for the advancement of Black Americans was initially named the Niagara Movement, based on that first meeting in Canada, there was no mention of Black Canadians at this historic meeting.

The story of this meeting helps to demonstrate the ongoing invisibility of Black Canadians both within Canada, across North America and internationally.

Given the strong geographical connection between Canada and the U.S., it is reasonable to question why Black Canadians are missing from the Niagara Movement’s historical narrative.

Their absence in this history highlights the erasure of the contributions of Indigenous, Black people and other racialized peoples in Canada. This Canadian historical narrative, as Canadian sociologist Rinaldo Walcott suggests, has effectively “invisibilized” the Black presence in Canada.

In his book, Black Like Who?, Walcott speculates that the NAACP disallowed Black Canadians from attending this first meeting, despite their attempts to engage in dialogue with the organizers. Walcott writes that there were Black people in Canada who had both heard of and wanted to participate in the movement. However, he believes they were not welcomed.

Many know that Black Americans faced racist laws meant to segregate and oppress their existence, but many do not realize that Black Canadians also faced the hardship of anti-Black racism or the extent to which they suffered.

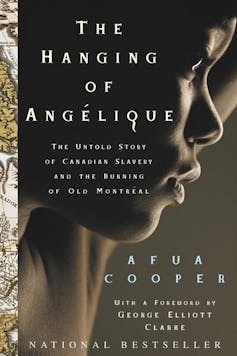

Historian Afua Cooper’s portrayal of enslaved woman Marie Joseph Angelique, accused of “allegedly setting fire to Montréal in 1734” in The Hanging of Angelique, helps to illuminate anti-Black racism and the enslavement of Black people in Canada in the 1700s. Although there was no direct evidence to prove Angelique caused the blaze, “she was convicted on circumstantial evidence in a justice system that declared defendants guilty unless proven innocent, by a court whose members had all suffered losses in the fire and by 24 vengeful witnesses, including a 5 year old girl.”

Cooper’s example helps to demonstrate the Canadian settler social conditions where Black people are assumed to be guilty.

The urgent need for a social justice movement

Black people in both Canada and the United States have encountered, and continue to face, a white settler terrain that loathes Blackness. After the Civil War, the United States Congress passed laws to support newly freed African-Americans but in the decades that followed, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a series of decisions that set back those efforts.

During that time, Black Americans encountered “anti-Negro” race riots. Historian Charles Kellogg recounts stories from African-Americans in places like Springfield, Illinois, where they encountered white mobs that burned down Black homes, lynched Black bodies and murdered Black people.

By 1905, the need for a social movement for African-Americans was urgent.

The NAACP would become the vehicle to increase the social citizenship of Black people in America, especially during the early 1900s, when the race divide cut deep and afflicted the social, political and economic conditions of Black folk.

U.S. segregation laws in the 1900s made holding meetings in hotels impossible. Efforts to hold the original meeting in Buffalo, New York were thwarted by a social climate that was simmering with racial hostility toward Black Americans. In historical notes, Buffalo’s NAACP chapter president, Rev. Mark Blue, mentioned that Black American thinkers were accepted by the management of the Erie Hotel, near Niagara Falls, Ont.

Why were Black Americans but not Black Canadians allowed at this historic meeting? Who disallowed them to enter? Was it the hotel managers? Was it the organizers? Were they there but perhaps not mentioned?

Invisible in Canada

Canada often characterizes itself as a haven for Black slaves of the American South, but it does so without acknowledging its own participation in the Black slave industry.

A seldom mentioned historical fact is that Canada has its own Black slave history. Prior to abolition, Black enslavement existed in Canada until it was abolished throughout British North America.

Before the Niagara Movement, the Canadian region was the site of safer passage of Blacks fleeing slavery in the United States. Heroic figures like Harriet Tubman travelled through Niagara, Canada to bring slaves to a better life in northern North America. Yet, as Walcott points out, there is little or no reference to these facts in the historical commentaries on the Niagara Movement.

Black Canadian historical moments, such as the destruction of Africville in 1967, live “only in the memories of its former inhabitants and their descendants.” Few know that “Halifax was founded in 1749, when African people held as slaves dug out roads and built much of the city.”

The lack of information about these histories is another form of anti-Black racism that exists in Canada. Canada has adopted a policy of erasure when it comes to acknowledging the history and contributions of its Indigenous and Black peoples.

Many scholars have asserted the importance of continued Black Canadian cultural studies. The power politics of whose work gets published, and where, and the absence of Black, Indigenous and racialized histories have reinforced Black invisibility.

It is necessary to critically engage on historical notions of Blackness and the “cross border political identification” of Black Canadians and Americans. By recognizing that both Black Canadian and American historical episodes of anti-Black racism are similar, we question how the white settler terrain has convinced mainstream society to believe one is worse than the other.

This is an updated version of a story originally published on Feb. 14, 2019. It clarifies the location of the Niagara Movement’s first meeting.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Thursday, February 14, 2019 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook