By Dan Rubinstein

When Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Paul Watson is reporting from the field, he searches for one element — a smell, a sound, an article of clothing — that will transport his audience from the comfort of their homes to the chaos of conflict.

In 1993, the public response to Watson’s photograph of a dead American soldier being dragged by a mob through the streets of Mogadishu — the picture that earned him a Pulitzer, shot during the military intervention dramatized in the Hollywood film Black Hawk Down — catalyzed the U.S. decision to pull its troops out of Somalia.

That’s the type of impact a journalist can have when they cover violent events on the other side of the world, says Watson, who will be one of the keynote speakers at “Media and Mass Atrocity: the Rwanda Genocide and Beyond,” a roundtable at Carleton from Dec. 1 to 3, 2017 organized and chaired by Journalism Prof. Allan Thompson.

Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Paul Watson

“The point of journalism is to make change — and to do that you need to get people to care,” says Watson, an author, writer and photographer who has covered conflicts in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Europe for publications such as the Los Angeles Times and Toronto Star.

The fighting in Syria is the most documented war in history, he continues, yet because access to the country is exceedingly difficult and dangerous for journalists, much of the coverage has come via social media posts from amateur observers — a barrage of unsubstantiated content produced by people who don’t necessarily think about the ethics of their actions and may have partisan objectives.

“My job is to find a way to tell the truth,” says Watson, “and get the public to engage when the natural inclination is to turn away.”

The Relationship Between Conflict and Media Coverage

The relationship between conflict and media coverage will be the focus of the Carleton roundtable, which will bring together 25 experts from academia and journalism, plus special guest speakers such as Roméo Dallaire, the former commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda who now helms a research, training and advocacy initiative aimed at eradicating the use and recruitment of child soldiers.

“In an era of social media saturation, near-ubiquitous mobile device penetration and dramatic shifts in traditional news media, it is more important than ever to examine the nexus between media and mass atrocity,” Thompson writes on the roundtable’s website.

“Advances in information and communications technology have reshaped the media landscape, rendering mass atrocities in distant countries more immediate and harder to ignore. And yet, a cohesive international response to mass atrocities has been elusive.”

In the mid-1990s, when Thompson began covering the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide as a Toronto Star reporter, there were no smartphones and the Internet was still in its infancy.

Hate radio had played a central role in the genocide. A Rwandan radio station’s broadcasts incited violence against members of the minority Tutsi ethnicity and members of the majority Hutu ethnicity who supported peace or married Tutsis.

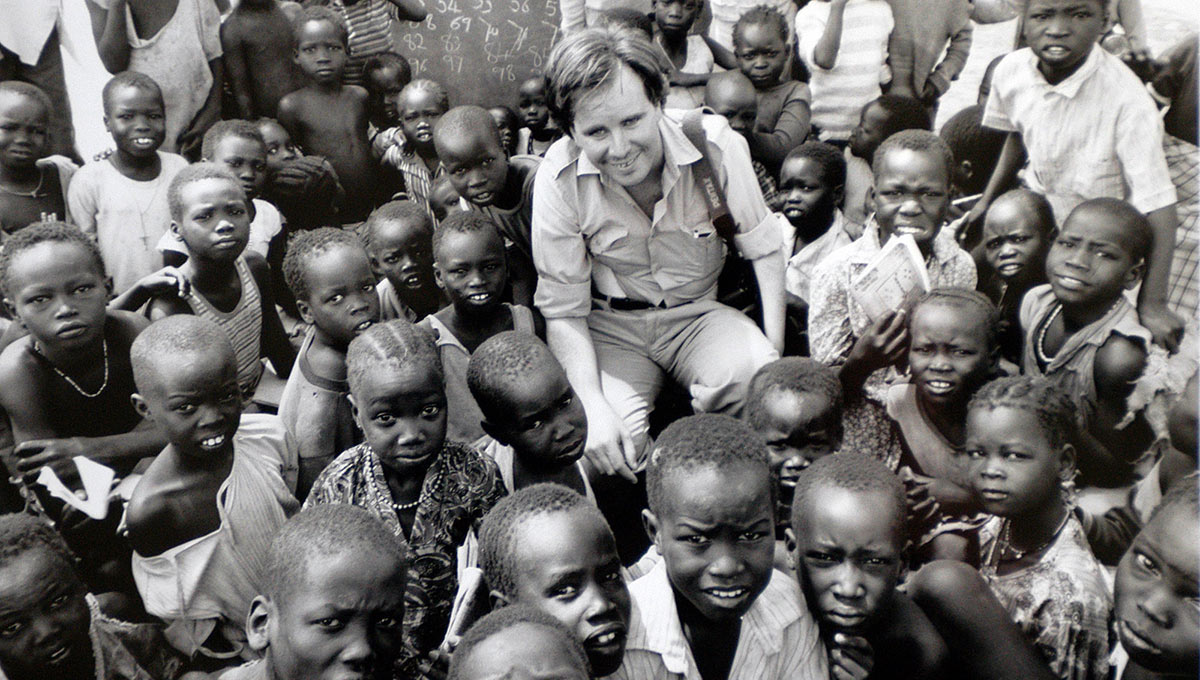

Paul Watson during the civil war in southern Sudan

From April to July 1994, approximately 800,000 people were killed, mostly Tutsis, and two million mostly Hutu refugees fled after a Tutsi-led party gained control of the country.

The international response to the horrific violence was late and ineffective, says Thompson, because there wasn’t a critical mass of media coverage to make people understand what was happening beyond “African tribal bloodletting.”

“Political leaders knew what was going on but didn’t want to get involved in another international swamp just a year after Somalia.”

Today, social media multiplies the attention traditional news organizations devote to international conflict. Even in countries such as Rwanda, most people have cellphones.

The content we’re exposed to can come from citizen journalists, militant groups such as ISIS, interested parties in distant nations such as Russia, or from NGO and humanitarian workers on the ground in a crisis zone. It can increase awareness, or it can contort facts and mobilize extremism — or any and all possible reactions in between.

“It’s astonishing the number of people who get their news through captions on Instagram photos,” says Thompson. “It’s a news environment that we don’t fully understand, and there’s a media literacy lesson to this. We need to understand how we learn about mass atrocities and how this shapes our response.”

Making Sense of Media and Mass Atrocity

In 2004, the 10th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, Thompson hosted a symposium at Carleton and edited a book that emerged from the event called The Media and the Rwanda Genocide.

Now the newly appointed senior fellow in the Global Security and Politics program at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) is working on a follow-up book that CIGI plans to publish in 2019 to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the genocide.

The roundtable, which is open to the public, will serve as a brainstorming session for a couple dozen potential contributors. Thompson also hopes to attract people from Carleton programs such as the School of Journalism and Communication, the Bachelor of Global and International Studies, the Norman Patterson School of International Affairs, as well as members of Ottawa’s foreign affairs and national defence communities.

Prof. Allan Thompson in Kigali, Rwanda

Despite the challenge of penetrating public consciousness in today’s frenetic media landscape, Thompson is not pessimistic about the positive role journalists can play.

“Hundreds of thousands of deaths can become a blur, but if you can make people connect with an individual victim, everything changes,” he says, mentioning the widely shared photo of Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old boy from Syria who drowned while trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea with his family — a death that informed conversations about the refugee crisis in Canada and beyond. “The power of narrative storytelling can make people care.”

Into the Field

During his talk at the roundtable, Watson plans to take participants “into the field” with him so they gain a deeper understanding of what journalists face when reporting from a war zone.

The post-9/11 surge in “embedded” journalists — reporters who file stories after riding around in armoured vehicles with western soldiers — is the opposite of what he does, he says.

Moreover, Hollywood films — even gritty movies that purport to convey reality — never capture the fact that you’re tired, dirty and physically and psychologically ailing much of the time when covering conflict or famine.

Paul Watson in the field

Traditional media outlets don’t want to pay — and pay for the necessary insurance — to station reporters in violent places, says Watson. And the path he took to become a war correspondent, freelancing photos to the Star during his summer vacation from the paper, is a longshot for young journalists looking to land full-time work in today’s media industry.

Yet photography, video and communications equipment is getting more portable and cheaper, and some people feel they absolutely must cover wars and are willing to accept the risks.

The public — and academics — depend on these journalists for information, says Watson. And once out in the field, they quickly come to understand the most important lesson of war: “the size and amount of the lies.”

The U.S. is currently ensnarled in the longest war in its history in Afghanistan because most Americans are oblivious to what’s happening, he argues.

“Their government is lying to them and, just like in Vietnam, soldiers are being sent to their deaths,” says Watson. “We live in an age when people derisively talk about ‘fake news,’ and there is a lot of fake news in foreign reporting, but there are also a lot of journalists making sacrifices to try to tell the truth.”

Wednesday, November 29, 2017 in Journalism and Communication, Public Affairs

Share: Twitter, Facebook