By Randy Boswell and Jonathan Swainger

In her bombshell testimony before a House of Commons committee, Jody Wilson-Raybould, Canada’s former minister of justice and attorney general, described repeated attempts at “political interference” by top government officials.

She told of “veiled threats” about her job and dark warnings about being headed for “a collision” with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau over the issue of helping Québec engineering firm SNC-Lavalin avoid a bribery trial.

Less dramatically — but with the potential to spark a major restructuring of her former ministry — Wilson-Raybould stated that she has long believed Canada should re-examine the conjoined federal department headed by the minister of justice and attorney general and consider “whether or not those two roles should be bifurcated.”

JWR says she believes the roles of Minister of Justice and Attorney General be split.

After this incident, hard to disagree. #JUST #cdnpoli— Dale Smith (@journo_dale) February 27, 2019

She added that a new structure could see an attorney general who would “not sit around the cabinet table,” referencing the British model that separates the justice minister and attorney general roles.

In the U.K., the office of the Attorney General, a non-cabinet post, is separate from the cabinet position of Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice.

Splitting the two jobs in Canada is an idea that was raised recently by University of Ottawa law professor Adam Dodek, who advanced a timely and important argument about what he calls an “intolerable conflict” within the combined role of minister of justice and attorney general in Canada.

The conjoined cabinet post, he insists, is at the heart of the Wilson-Raybould controversy.

He argued it’s time to sever the political, partisan role of the minister of justice from that of the ideally “independent” attorney general — the government’s chief legal adviser and litigator, someone expected to “put aside partisan concerns” in upholding the Constitution. It seems Wilson-Raybould agrees.

Don’t ignore the history

This is all good fodder for serious debate. But we shouldn’t embark on potential reforms by ignoring the history that led to the 1868 creation of this country’s Department of Justice and the yoking of the minister of justice and attorney general jobs in a single cabinet position.

Neither should we necessarily graft British appendages onto our body politic. As early as the 1840s, leading political reformers such as Robert Baldwin believed a policy-engaged, made-in-Canada version of attorney general “clothed with its present political character” was required “in a community like ours.”

Furthermore, we shouldn’t naively imagine that splitting these positions will somehow magically insulate government legal thinking from the sullying effects or pragmatic influences of politics.

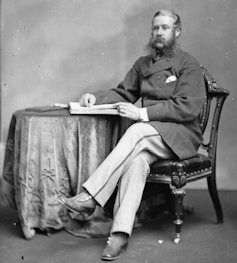

There are, in fact, deep-rooted historical reasons why Canada has a combined minister of justice and attorney general. And as with many other contentious issues in modern Canada, to better understand this ministry we must reflect on the mixed legacy of Canada’s founding prime minister — who was also the first minister of justice and attorney general.

Yes, it could be argued that Sir John A. Macdonald, so often a target for contemporary critics, is ultimately to blame for the Wilson-Raybould affair, too.

Filled the job himself

Or should we credit Macdonald’s peculiar genius for statecraft — including the imperfect but practical compromise he struck between the political and legal imperatives of government — when he created the unified ministerial position in 1868 and promptly filled the job himself?

It’s worth noting that the ministry was formed after Washington spy George W. Brega provided Macdonald with a blueprint of planned changes to the U.S. Attorney General’s office. These matched the kind of dual-role ministry Macdonald was already planning for Ottawa.

The legislation that created Canada’s justice ministry was crafted by Macdonald and his brother-in-law, Hewitt Bernard, deputy attorney general at the time. The project reflected Macdonald’s understanding of 19th-century realpolitik and — as head of a fragile, complicated new country — his perceived need for the law of the land to be informed by, and sometimes governed by, political considerations.

You can hear echoes of Macdonald when Trudeau — in response to accusations of political interference in the SNC-Lavalin case — refers to his government’s commitment “to defend jobs and to make sure that our economy is growing” while simultaneously “upholding the rule of law.”

Unspoken (but also discernible in the government’s handling of the case) are concerns about Liberal election fortunes in Quebec — concerns referenced by Wilson-Raybould in her testimony.

While Macdonald often spoke about the sanctity of the law, he was a pragmatist. He excelled at working in the small spaces and along the edges of the law — in the service of the national interest, as he saw it, but also in his party’s interests.

In the case of the Pacific Scandal, Macdonald wandered well past the edge of the law. He was consequently exiled from the prime ministership for five years following allegations his government accepted election funds from a shipping magnate in exchange for the contract to build the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway.

The realities of governing

Macdonald probably spoke of the attorney general being responsible for astute legal counsel. It’s not hard to imagine he likely nodded and winked at the realities of how the business of government actually worked in his day.

Thus the two offices were fused then — and remain so today — because of Macdonald’s sense of how government ought to function. Canada didn’t get a joint minister of justice and attorney general “just because;” it’s the result of Macdonald’s very conscious decisions, and his acceptance of the idea that, of course, legal decisions are political.

The dual position has endured under 22 subsequent prime ministers, both Conservative and Liberal.

But times have changed. As Prof. Dodek rightly points out, conflict-of-interest rules and other guiding principles of good governance have evolved. We may well be able to fashion a better ministerial structure in the 21st century than was envisioned 150 years ago.

But even if we think Macdonald rather cynical, we may find that keeping the justice and attorney general jobs together under one minister is still the best arrangement for this country.

In any case, we shouldn’t approach this worthwhile debate blind to the peculiarities of Canadian history nor swayed too much by the fiction of an apolitical attorney general — whether wearing one hat or two.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Wednesday, February 27, 2019 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook