By Dan Rubinstein

Photos by Susan Ross

There was a snowstorm raging when Carleton Prof. Susan Ross first took her students to Ottawa’s Macdonald Gardens Park, a diverse pocket of apartment towers, walk-ups, single-family homes and a few institutional buildings tucked into the easternmost corner of Lowertown, between Rideau and St. Patrick streets along the Rideau River.

As the group from CDNS 5402 — a graduate seminar in heritage conservation in the university’s School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies — walked around the neighbourhood with longtime local Nancy Miller Chenier, co-chair of the Lowertown Community Association (LCA) heritage committee, they passed through the green space at the core of the community.

Macdonald Gardens Park, eight acres of manicured lawns, mature vegetation and winding paths presided over by a hexagonal hilltop stone summer house, is well used and loved by area residents. But its historical significance — like that of the surrounding neighbourhood — is largely overlooked in a city of grand federal promenades and stately government buildings.

An archival photo of the hexagonal hilltop stone summer house that presides over Macdonald Gardens Park

So Ross and seven master’s students decided to make Macdonald Gardens Park the focus of their winter term study in community heritage. And their efforts helped the LCA secure an official heritage designation for the park, which celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2014, from the City of Ottawa in June 2017.

This type of recognition, unprecedented for a park in Ottawa, has both tangible and symbolic implications. The heritage status not only provides a check on development to the park and surrounding streetscape, it also draws overdue attention to the site of one of Ottawa’s oldest cemeteries, an urban oasis designed by pioneering landscape architect Frederick G. Todd — and the heart of a vibrant neighbourhood whose evolution reflects several interesting chapters in the growth of the national capital.

“Macdonald Gardens Park has been enshrined as a commemorative landscape,” says Ross. “This will help keep the space open, and creates the potential for remembering.”

Enshrining Macdonald Gardens Park As a Commemorative Landscape

The seeds of the Macdonald Gardens Park project were planted before Ross joined the faculty at Carleton in December 2013.

After working as an architect, she had spent the previous 11 years developing an understanding of heritage conservation policy issues in the federal government’s Heritage Conservation Directorate. Miller Chenier and others in the LCA learned that Ross would be starting at the university and encouraged her to take a closer look at Macdonald Gardens.

That suggestion brought Ross and a multi-disciplinary group of grad students interested in social history, architectural heritage and planning policy to the neighbourhood during the aforementioned snowstorm in January 2014.

Their field observations that day were limited by the weather, but the more they discovered about the history of Macdonald Gardens, the more they realized they could help the LCA document its significance and make a stronger case for conservation.

“Macdonald Gardens has a fascinating story,” says Ross, “but it’s under pressure and changing building by building, and nobody seemed to be able to do anything about it.

“Our project was very much driven by the community. It’s easier as a professional to consult with an authority and produce a report. It’s more challenging to work with a community; you’re bringing them into a context they have to temporarily master. You have to really understand their needs and be a bridge. One of my goals was to expose students to community questions and perspectives.”

“A community can plod along and do research when volunteers have time,” says Miller Chenier, “but Susan and her students made us think differently, and gave us extra credibility with the city.”

Delving into the History of the Park

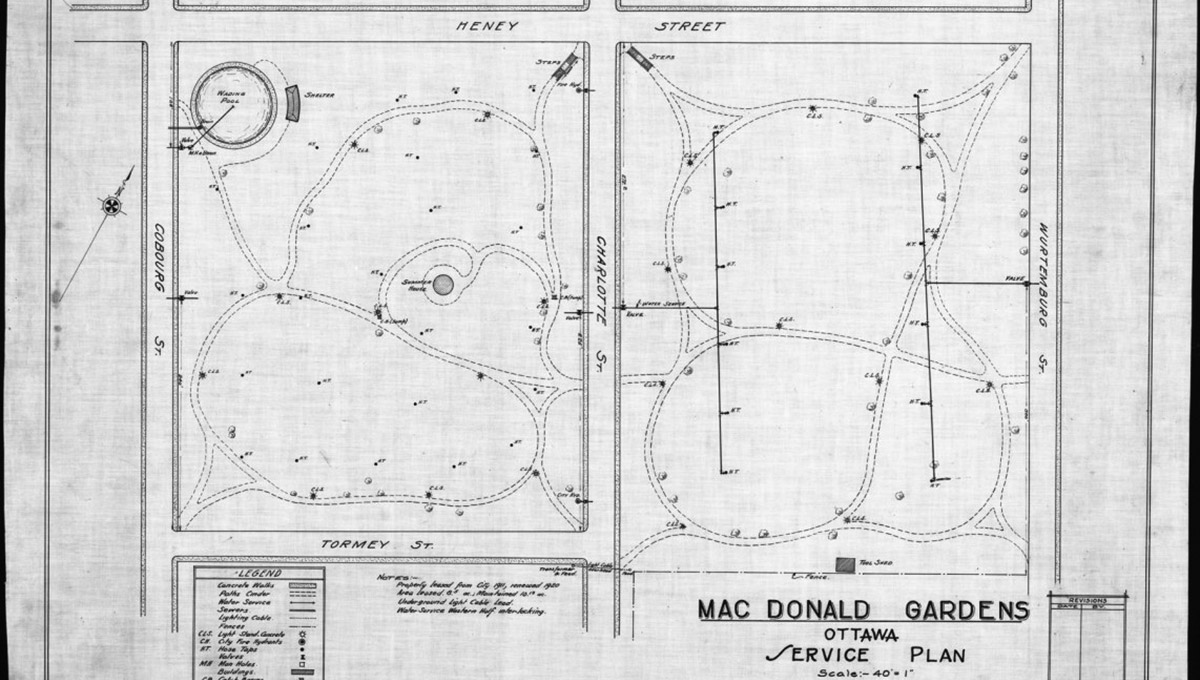

Carleton students conducted archival research, analyzed relevant planning policies and studied historical maps. Because it was too problematic to determine boundaries of the broader neighbourhood around the park for a heritage designation pitch, the LCA subsequently concentrated on the park.

Between 1845 and 1873, the site was used as a cemetery by the Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Wesleyan Methodist and Roman Catholic churches. The cemeteries fell into disrepair in the 1870s and over the next three decades human remains were moved to the new Beechwood and Notre Dame cemeteries, although there are reports that some graves were left behind. (In 1911, city council minutes listed 250 names compiled from the remaining legible gravestones).

The Ottawa Improvement Commission, forerunner of the National Capital Commission, began creating a park in 1912. It was to be part of a capital parkway system and the scenic driving route to the downtown core.

Prof. Susan Ross

Todd, who apprenticed under Frederick Law Olmstead, the father of American landscape architecture and the co-creator of New York City’s Central Park, was brought in to design the park — his only completed project in Ottawa. (Todd had also developed an official plan for the Ottawa Improvement Commission in 1903, the city’s first green space plan).

Beyond the features of the park, which include a view of the Parliament Buildings from the hill where the gazebo-like summer house was built, the nearby streets have several points of historical interest, including the home of former prime minister Robert Borden, who lived directly across from the park on Wurtemburg Street for 30 years and, at the corner of Charlotte and Rideau streets, Wallis House, a circa 1876 hospital that became a Roman Catholic seminary, a military facility and is currently an upscale condo complex.

The mix of housing in the Macdonald Gardens neighbourhood, built between the late 1800s and the start of the new millennium, “shows a variety of housing that is rarely found elsewhere in such a combination,” reads the CDNS 5402 report, written in the summer of 2014 by then-master’s student Victoria Ellis, who Ross had hired to remain involved as a research assistant.

That’s because the waves of urban renewal that swept through Lowertown and other parts of Ottawa after the Second World War, razing and redeveloping large tracts of housing, didn’t have as large an impact in Macdonald Gardens.

Similarly, the mix of people in the neighbourhood remained distinctively diverse — “a resilient community,” according to the report, “able to evolve and accommodate change.”

Studying the neighbourhood and park, and producing an in-depth report, “speaks to not only thinking of ‘heritage’ as officially designated heritage,” says Ross. “It’s also about whether a community cares, and how a community can come together to help build up awareness.”

A Microcosm of Local History

Ellis recalls feeling that Macdonald Gardens was a special place the first time she walked through the neighbourhood.

Meeting Miller Chenier and other locals, learning about the area’s history and finding out how much the park and surrounding streets meant to the community, affirmed the sensation.

“It has so many layers of history,” says Ellis. “It’s a microcosm of Ottawa’s planning history.”

Nancy Miller Chenier and Victoria Ellis

Ellis, who is now a web editor at the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, considers the Macdonald Gardens project the most memorable experience of her master’s degree program at Carleton.

“I got so much out of it. I really felt like I was directly helping a community,” she says. “My interest has always been in storytelling. That’s what I love to do — to help people tell complex stories in a meaningful way.”

Establishing a Heritage Committee

Although she has lived in Lowertown for nearly 40 years, Miller Chenier didn’t get involved in the community association until 2011, when she helped establish its heritage committee.

Increasingly aware of how vulnerable the built architecture was in the area, she helped secure a Canada Summer Jobs grant in 2013, and every summer since then has hired students (including Carleton students) to research and document local history.

Miller Chenier also began looking into the histories of different parks in the area and, in 2014, when the LCA decided to commemorate the centennial of Macdonald Gardens Park, Ross was asked to help dig into the past.

“It’s up to the community to push these sorts of things,” she says about the successful bid for the park’s heritage designation, “but what Susan and the students did was key. They provided us with such strong material.”

Local residents enjoy Macdonald Gardens during the summer

The new official status of Macdonald Gardens Park could inspire the LCA to make more substantial heritage conservations “asks” of the city, says Miller Chenier, and could ensure that nearby buildings get a second look if a developer proposes a demolition and rebuild.

But it’s the intangible and human dimension that really excites her.

While researching the park’s past, the Carleton team heard personal stories that showed how much affection people have for the site. It’s where they first kissed their boyfriends or girlfriends, where marriages were proposed, where generations of children tobogganed, where kids found bones from the former graveyards, where they splashed around in a wading pool that was eventually closed (to the applause of neighbours annoyed by the noise), where people climbed the hill to sit in the shade of the summer house and catch the breeze on hot days.

“There’s a newfound sense of pride and sense of place,” says Miller Chenier. “It’s not just about grand mansions — this is a community, and this is our park.”

Wednesday, December 6, 2017 in Architecture, Community

Share: Twitter, Facebook