By Sissi De Flaviis

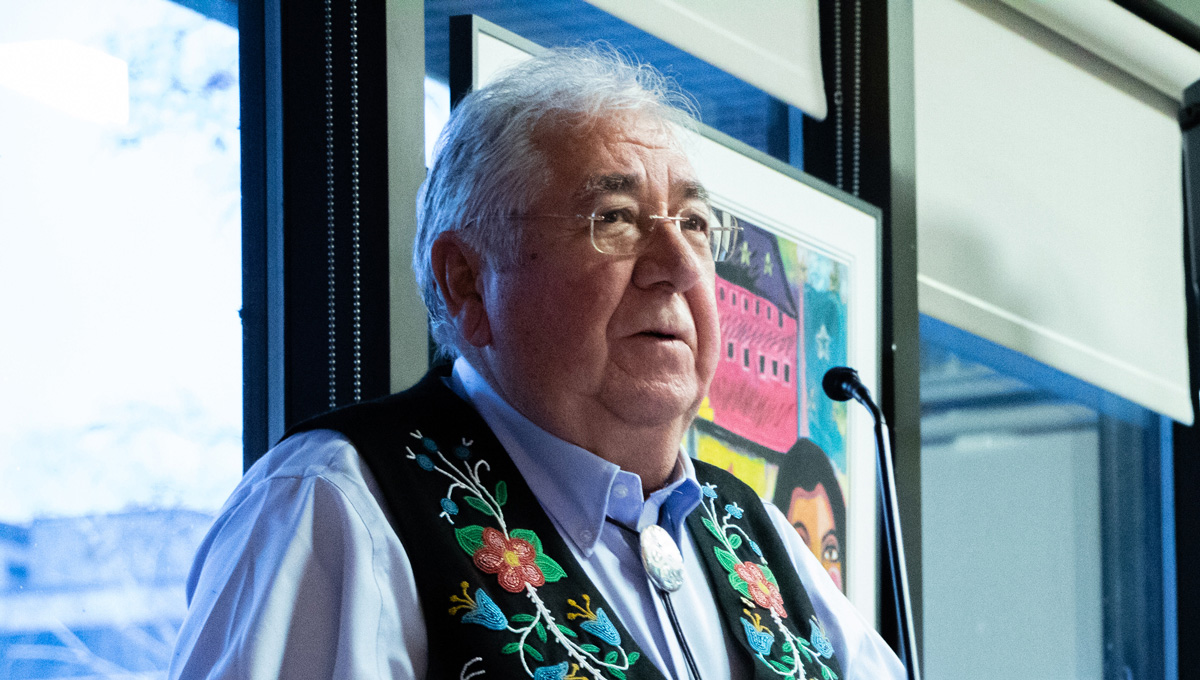

Carleton University’s Centre for Indigenous Initiatives (CII) marked Louis Riel Day on Nov. 16, 2020 with an online session led by Métis Elder Tony Belcourt.

Belcourt is a knowledge keeper and longtime Métis rights advocate who spoke on the important contributions and history of Métis people in Canada.

The two-hour gathering began with Belcourt speaking about his experiences growing up in a Métis-French community near Edmonton, followed by the history of Louis Riel.

Theresa Hendricks

Theresa Hendricks, a Métis person and CII’s Indigenous Special Projects and Administrative Coordinator, said listening to Belcourt was an honour.

“Learning about Métis history through someone with a wealth of knowledge on the subject is an experience many Canadians would benefit from,” said Hendricks.

“This kind of knowledge is not widely known.”

History Behind Louis Riel Day

Louis Riel Day is a significant one in the Métis community as it commemorates Riel’s life, Métis culture, language, heritage and homeland.

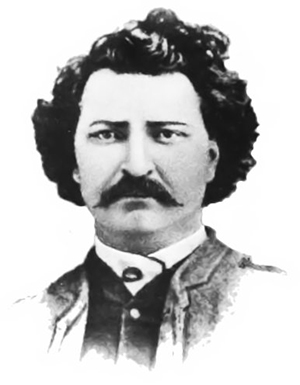

Louis Riel (Photo: I. Bennetto & Co.)

Oliver Thorne, a Carleton master’s student in Indigenous and Canadian Studies, said the session showed him how the narrative about Riel has shifted with time.

“Originally, Louis was looked at by the state, specifically by Prime Minister John A. McDonald, (as) a thorn in their side. But now, that narrative has shifted to an original proponent of multiculturalism and diversity in Canada,” said Thorne, who believes this national narrative should be critically analyzed.

In the 1800s, Riel was an advocate for Métis and minority rights, such as preservation of French language and Indigenous rights to land.

Riel was elected as a Member of Parliament. However, he never sat in the House of Commons due to being prosecuted as a traitor to the government, explained Belcourt.

After years of fighting for Indigenous and French rights, Riel was hung in 1885.

Growing up Métis in the 1940s to 1960s

Belcourt narrated how his father lived off the land, from hunting to fishing to trapping—as many Métis did, too—and how winter presented a struggle for numerous members of the community due to lack of food sources.

“I didn’t realize how poor we were,” said Belcourt.

“Sometimes we would go into the store and I would see all these vegetables and foods like banana and wonder what they would taste like.”

He then referred to the historical relevance of the church and its conceptualization of Indigenous people.

Belcourt explained how Métis and First Nations people were only allowed to go to mass during the week, while French folks would go during the weekend, usually on Sunday.

“On Indian day—as they called it—the priest sent a message that we were all sinners and awful people,” said Belcourt.

One day, when Belcourt was 22 years old, he ventured into Sunday mass.

“I was curious and went on French day. The atmosphere was different. The priest would say: ‘Oh, you wonderful children of God.’

“This shows how much there was a difference between how people saw us and how people saw (other) people,” said Belcourt.

Friday, November 20, 2020 in Events, History, Indigenous

Share: Twitter, Facebook