By Hyounjeong Yoo

At this year’s Oscars, Chloé Zhao became the first woman of colour to win the award for best director for Nomadland. Youn Yuh-jung also became the first Korean actress to win an Oscar for her role in Minari.

After decades of being excluded from, and stereotyped by Hollywood, East Asians are finally being recognized in the film industry. This degree of recognition is a cause for celebration, but there is still a long way to go.

For decades, the predominantly white western film industry has confined Asian actors to stereotypical roles and even cast white actors to play Asian characters. But the recent success of Asians in the film industry begins to open the door to more prominent Asian roles in this field.

A new Korean wave is helping to significantly break down barriers and deconstruct the representation of Asians in western media.

The power of representation

I grew up watching Hollywood cinema in South Korea and was especially fond of Katharine Hepburn. Her role in the 1944 film Dragon Seed left a lasting impression.

In the movie, Hepburn plays a Chinese woman with awkward makeup. When I first saw the film I was only eight years old and had never been to China, but I knew what a Chinese person looked like and it was not that. I wondered whether this casting choice was because there were no Asians in America, or because Asian women weren’t as pretty as Hepburn. I was gaslighted into believing Asian women couldn’t be the central character because we aren’t attractive.

(AP Photo/Chris Pizzello, Pool)

Despite almost 50 years of Canadian multiculturalism, Asian people are still facing discrimination and stereotyping around being a model minority.

With the rise in anti-Asian racism during the pandemic and recent violent attacks in the United States and Canada, Asian people are increasingly becoming fearful about their place in North American society.

As a Korean language instructor at Carleton University, my classes are made up of students from multiple cultural and ethnic backgrounds. During one of my classes, I decided to show a music video by the K-pop band BTS to engage students in contemporary Korean culture.

After playing DNA by BTS, I was surprised to see how it was able to break down cultural and language barriers. Students who had not yet spoken began chatting like they had known each other for a long time. Research shows that music brings people together.

East Asian students continue to see the accomplishments of K-pop artists as their own. One of my students, a second-generation immigrant from Vietnam said: “I feel indebted to BTS. I am wounded because I am underrepresented in a society where I should belong, but I feel healed by them.”

In the long history of Western pop-culture, non-western cultures have too often been portrayed as tacky subcultures or disparaged racial minorities. The rise of K-pop is helping reset these stereotypes and, within Asian communities in North America, has become a remedy for those who are perpetually made to feel like foreigners in their own country.

The Korean wave

From BTS to video game competitions and the noteworthy 2016 K-drama, Goblin, the Korean wave is taking western audiences by storm.

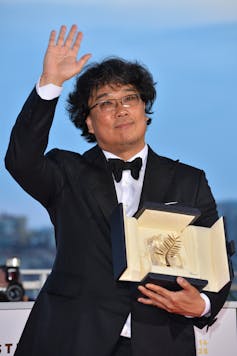

Netflix is planning to invest $500 million this year in South Korean films and TV series. Korean movies and dramas like Parasite, Train to Busan and the 2006 cult classic The Host have received critical acclaim globally and in North America.

Korean dramas consistently provide solid performances through impeccable storytelling. One example is the Korean drama Kingdom, Netflix’s first original Korean series.

Kingdom is more than just a cliché zombie show. With its spectacular landscapes and complex characters, Kingdom holds its own in the competitive streaming space. This challenges the sentiment that mainstream content with Asian actors as leads is inferior.

The influx of Korean content can do a great deal to reduce racist attitudes and alter perceptions of East Asians by normalizing the presence of Asian people on screen, in magazines, on the radio and in broader society.

As a Korean, I feel fulfilled when I watch series and films filled with faces like mine, portraying complex characters and telling stories not restricted by Western stereotypes.

There are still major hurdles to overcome that prevent Asians from getting into the mainstream. However, Korean content is a powerful way of providing healthy Asian representation and transcending racist stereotypes.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Carleton University is a member of this unique digital journalism platform that launched in June 2017 to boost visibility of Canada’s academic faculty and researchers. Interested in writing a piece? Please contact Steven Reid or sign up to become an author.

All photos provided by The Conversation from various sources.

![]()

Sunday, May 30, 2021 in The Conversation

Share: Twitter, Facebook